Baskin’s Crane

[Posted by Justin Martin for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

[Posted by Justin Martin for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

Hart Crane’s visage (who could mistake his decimating eyes) stares from atop a torso-like mass of dark veins and lines on the second title page of Voyages: Six Poems by Hart Crane, an artistic rendering of Crane’s celebrated erotic suite published 25 years after his suicide. The poems, which feature threads of nautical imagery throughout, take on strange new meaning in the print: “The sea lifts, also, it’s reliquary hands.” Hart Crane now lies somewhere within that sea, and his poetry continues to find new light and appreciation in his absence, in this case in the accompaniment of Leonard Baskin’s wood engravings, which, as well, are a part of the bold title card pasted to the front of the book’s four-fold case.

Leonard Baskin, born in 1922, was 10 years old when Hart Crane passed away. In 1942, while studying at Yale University, Baskin founded the Gehenna Press, initially for the purpose of publishing fine pressings of his own works – the company’s first two releases were books of Baskin’s own poetry and wood engravings, respectively. These first two books, On a Pyre of Withered Roses and A Little Book of Natural History, were published nine years apart, the second’s release delayed by Baskin’s time serving in WWII. Baskin’s purpose in founding and developing the Gehenna Press, one might speculate, was to follow the lead of William Blake’s duality as poet and bookmaker. Leonard’s poetry on its own never claimed much right to legacy, but he certainly had insights into the workings of the craft and an appreciation for influential predecessors like Crane.

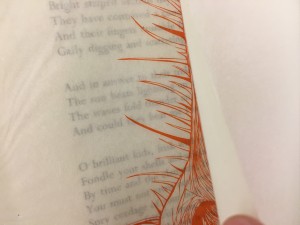

The book itself mimics the qualities Crane takes on at times in the Voyages: sensitive, textured, always hinting at something deep and monstrous beyond the surface. Crane’s poetry is printed on Amalfi handmade paper, accompanied by seven of Baskin’s engravings printed in one instance on the aforementioned Amalfi paper, but for the most part on much thinner, transparent japanese paper, which is, in one instance, bound into the book’s spine, and, otherwise, pasted quite precariously onto the other, thicker pages.

The book itself mimics the qualities Crane takes on at times in the Voyages: sensitive, textured, always hinting at something deep and monstrous beyond the surface. Crane’s poetry is printed on Amalfi handmade paper, accompanied by seven of Baskin’s engravings printed in one instance on the aforementioned Amalfi paper, but for the most part on much thinner, transparent japanese paper, which is, in one instance, bound into the book’s spine, and, otherwise, pasted quite precariously onto the other, thicker pages.

One particular print, a circular design which frames an abstract landscape of lines and fractured details, accompanies the third voyage, perhaps the most iconic of the six, on a green sheet of the thin japanese which is pasted across the top edge, horizontally, to the opposite page, left to hang unglued on all other sides, like some ghastly hanging curtain. Scattered vertical line fragments in the wave-like texture resemble “ribboned water lanes…/ laved and scattered…”

The book held at the Watkinson is one of 975 copies originally printed, all by hand. It is a slender little thing. The cover is worn, presumably by time. It commands a certain amount of spectacle as its quad-folding encasement opens at all angles, only to reveal the actual book inside to be near-identical to the encasement’s cover. The book itself forces one to be intimate with it: the thin, fragile Japanese pages peer out from behind their thicker, whiter counterparts, and, as one progresses through the Voyages, prove to be pasted in at differing angles, prompting one to constantly adjust their attention so as to avoid tearing the things out.

The book held at the Watkinson is one of 975 copies originally printed, all by hand. It is a slender little thing. The cover is worn, presumably by time. It commands a certain amount of spectacle as its quad-folding encasement opens at all angles, only to reveal the actual book inside to be near-identical to the encasement’s cover. The book itself forces one to be intimate with it: the thin, fragile Japanese pages peer out from behind their thicker, whiter counterparts, and, as one progresses through the Voyages, prove to be pasted in at differing angles, prompting one to constantly adjust their attention so as to avoid tearing the things out.

One of Baskin’s most powerful contributions to the poetry: the sprawling circuitry of a beak emerging from the engraving accompanying Voyage IV. The bird lies motionless on the page, its talons seemingly hanging from the mess of intricate lines which makes up the bird’s body (so delicately spacing out and unraveling within its breast). The cut is a haunting rendition of, perhaps, the “chilled albatross’ white immutability”.

A print of Voyages by Gehenna and the Museum of Modern Art could cost anywhere between $200 and $700, depending on wear on the copy and whether it is signed or not, and can be found fairly easily via a google search or on websites like Abebooks.com.

The print can be taken as a work firstly and perhaps solely done by Baskin himself, since its publishing date, 1957, is before Baskin turned over his position as sole printer of the Gehenna Press. Baskin obviously wanted to not only present, but interact with the poetry in his printing, creating an entirely new experience out of Crane’s Voyages, intimately giving texture, in both the two- and three-dimensional senses, to his verses. Crane’s eyes in his portrait seem to speak to this intimacy; their openness spills down into the sharp and tense mass of tendrils below, within the ribcage.

The print can be taken as a work firstly and perhaps solely done by Baskin himself, since its publishing date, 1957, is before Baskin turned over his position as sole printer of the Gehenna Press. Baskin obviously wanted to not only present, but interact with the poetry in his printing, creating an entirely new experience out of Crane’s Voyages, intimately giving texture, in both the two- and three-dimensional senses, to his verses. Crane’s eyes in his portrait seem to speak to this intimacy; their openness spills down into the sharp and tense mass of tendrils below, within the ribcage.