|

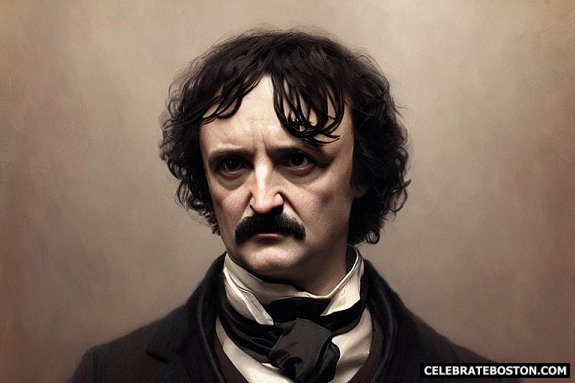

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

"No one who has written of poor Poe seems to have quite understood his case. Nor should I, if I had not spent a few days last summer at the Inebriate Asylum at Binghamton, in the State of New York.

Edgar A. Poe, like Byron and many others, appears to have been a man whose brain was permanently injured by alcohol, and so injured that there was no safety for him except in total and eternal abstinence from every intoxicating drink. I have often heard the late N. P. Willis speak of Poe's conduct when he was sub-editor of the "Evening Mirror," of which Mr. Willis was one of the editors. Poe, he would say, was usually one of the most quiet, regular, and gentlemanlike of men, remarkably neat in his person, elegant and orderly about his work, and wholly unexceptionable in conduct and demeanor.

But in a weak moment, tempted, perhaps, by a friend, or by the devil Opportunity, he would take one glass of wine or liquor. From that moment he was another being. His self-control was gone. An irresistible thirst for strong drink possessed him, and he would drink and drink and drink, as long as he could lift a glass to his lips. If he could not get good liquor, he would drink bad; all he desired was something fiercely stimulating. He would frequently keep this up for several days and nights, until, in fact, his system was perfectly exhausted, and he had been taken helpless and unresisting to bed. There he would lie, miserable and repentant, until he had in some degree recovered his health, when he would return to his labor, if the patience of his employers had not been exhausted.

Having formed this deplorable habit while his brain was immature, I believe that it then received an incurable injury, which caused it to generate unsound thoughts, erroneous opinions, and morbid feelings. His thinking apparatus was damaged, and he came upon the stage of life with a propensity toward absurdity and extravagance.

David Poe, of Maryland, the grandfather of the poet, was an officer of repute in the army of the Revolution. Like many other soldiers, he married when the war was over, and settled in the chief city of his native state, Baltimore. His eldest son, who was also named David, was destined to the law, and in due time entered the office of a Baltimore lawyer. This son was an ardent, impetuous youth, one of those ill-balanced young men who may, if circumstances favor, perform heroic actions, but who are much more likely to be guilty of rash and foolish ones. While he was still pursuing his studies, an English actress, named Elizabeth Arnold, appeared at the Baltimore theater. David Poe fell in love with her, as many young fellows before and since have done with ladies of that profession. More than that, he married her, abandoned his studies, and went upon the stage.

Having taken this desperate stop, he lived for a few years the wandering life of an actor, playing with his wife in the principal cities of the South. Three children were born to them, of whom Edgar, the eldest, first saw the light at Baltimore, in 1811. Six years after, Mr. and Mrs. David Poe were fulfilling an engagement at the theater in Richmond, Virginia. Within a short time of one another, they both died, leaving their three little children totally unprovided for. Edgar, at this time, was a lively, pretty boy, extremely engaging in his manners, and giving great promise of future talent. He was so fortunate as to attract the attention of Mr. John Allan, a rich merchant of Richmond, who adopted him, and who proceeded to afford him what he considered the best opportunities for education then existing.

When the boy was not quite seven years of age, he took him to London; and in a village near that city, he placed the little orphan at a boarding-school, where he left him for nearly five years. So far as is known, the child had not a friend, still less a relation, on that side of the ocean. Here was an eager, vivacious, and probably precocious boy, confined in the desolation of an English school; which is, generally speaking, a scene as unsuited to the proper nurture of the young, as Labrador [was] for the breeding of canary-birds. Such a boy as that needed the tenderness of women and the watchful care of an affectionate and wise father. He needed love, home, and the minute, fond attention which rare and curious plants usually receive, but which children seldom do, who are so much more worthy of it, and would reward it so much more. He needed, in short, all that he did not have, and he had in abundance much that he did not need. If the truth could be known, it would probably be found that Poe received at this school the germ of the evil which finally destroyed him. Certainly, he failed to acquire the self-control and strong principle which might have saved him. The head-master, it, appears, was a dignified clergyman of the Church of England, whom the little American was disposed to laugh at in his shabby suit of black on weekdays, though he regarded him with awe and admiration when on Sunday he donned his canonicals, and ascended the pulpit.

Poe was past eleven years of age—a pale, bright little boy—when Mr. Allan brought him home, and placed him at a school in Richmond. At a very early age, not much later than fourteen, he entered the Virginia University at Charlottesville, which Jefferson had founded, and over which the aged statesman was still affectionately watching, as the favorite child of his old age. At this university he became immediately distinguished, both in the class-room and out of doors. One of his biographers (who, however, was a notorious liar) tells us that, on a hot day in June, "he swam seven miles and a half against a tide running, probably, from two to three miles an hour." This is a manifest falsehood. Neither Byron, nor Leander, nor Franklin, nor any of the famous swimmers, could have performed such a feat. Nevertheless, he may have been an excellent swimmer, and may have excelled in the other sports proper to his age. The acquisition of knowledge was easy to him, and ho could without serious effort have carried off the highest honors of his class. But he drank to excess; and as drink is the ally of all the other vices, he gambled recklessly, and led so disorderly a life that he was expelled from the college. His adopted father refusing to pay his gambling debts, the young man wrote him a foolish, insulting letter, took passage for Europe, and set off, as he said, to assist the Greeks in their struggle for independence.

Of his adventures in Europe only two facts are known: for Poe was always curiously reticent respecting the events of his own life. One fact is, that he never reached Greece. The other is, that, about a year after his departure from America, he was arrested in St. Petersburg by the police, probably for an offense committed when he was drunk. The American minister procured his discharge, and finding him totally destitute of money, relieved his wants and paid his passage home. On reaching Richmond the prodigal was heartily welcomed by his benefactor, Allan, who soon pro cured for him a cadetship at West Point.

He appears to have entered that institution with a sincere determination to perform his duties, and become a good officer. For a while his behavior was excellent; he stood high in his class; and his friends hoped that he had sown his wild oats, and that he was now a reformed character.

But what an amount of falsehood is implied in that expression, he has sown his wild oats. The popular belief is, that a young man may go on drinking, carousing, gambling, and turning night into day, for a certain time, and then, suddenly changing his course of life, live the rest of his days as well and happily as though he had never gone astray. Miserable mistake! No one can abuse his body without paying the penalty, and, least of all, a man of delicate and refined organization like Edgar A. Poe. Such men as he are formed by nature for the exercise of the noblest virtues and the practice of the highest arts. A stronger and coarser nature than his, or one more mature, might have suffered for a while from the blighting fumes of alcohol, and then in some degree have recovered its tone, and made some amends for the wrong it had done.

It was not so with the tender and unformed organs of this young man, who never recovered from the injury which early dissipation had wrought. A few months after entering West Point, his appetite for drink resumed its sway, and he relapsed into his former habits. Before his first year had expired, he was expelled from the academy.

Again he returned to Richmond, and again his long-suffermg benefactor received him into his house. There he found the young and beautiful wife whom Mr. Allan had recently married; and to her, it is said, he paid attentions so marked that Mr. Allan was at length thoroughly incensed against him, and banished him forever from his house. A more probable version of the story is, that Mr. Allan, happy in the society of his wife, was less patient than before of his protégé's dissipated habits, and was easily set against him by the young lady. However it may be, John Allan died soon after, and, though he left a large fortune, poor Poe's name was not mentioned in his will. His death occurred in 1834, when Poe was twenty-three years of age.

The young man had published a small volume of poems at Baltimore in 1829, which attracted some attention, more on account of the youth of the writer than the merits of the writing. Being now destitute of all resource, he made some endeavors to procure literary employment. Failing in this, he enlisted in the army as a private soldier. While he was serving in the ranks, he was recognized by officers whom he had known at West Point, who, after inquiring into his case, applied for his discharge; but before the document arrived Poe deserted. He was not very closely pursued, however, and he soon found himself in Baltimore, a free man, but almost totally destitute. Then it was that he read in a paper an advertisement by the publisher of a literary periodical, offering two prizes of $100 each for the best story and the best poem that should be offered. Poe sent in both a story and a poem, won both prizes, and soon after obtained employment as editor of the "Southern Literary Messenger," then published at Richmond.

Again the same story: steady conduct and well-sustained industry for a short time; then drink, dissipation, and discharge. Before he was dismissed, he had married his cousin, Virginia Clemm, a very pretty, amiable girl, and exceedingly fond of her erratic husband. The ill-provided pair removed to New York in 1837, where he continued to live during the greater part of the rest of his life. Nothing new remains to be told. He frequently obtained respectable and sufficiently lucrative employment, but invariably lost it by misconduct, arising, as I think, solely from the effect of alcohol on his brain. In October, 1849, in the course of a Southern lecturing tour, he stopped at Baltimore, where, meeting some of his old companions, he spent a night in a wild debauch, and was found in the morning in the street suffering from delirium tremens. He was taken to the hospital, where, in a few days, he died, aged thirty-eight.

Poe was a mild-looking man, of pale, regular features, with a certain expression of weakness about the mouth, which men often have who are infirm of purpose. He had something of the erect military bearing noticeable in young men who have had a military drill in their youth. What with the neatness of his attire, the gentleness of his manners, and the pale beauty of his face, he usually excited an interest in those who met him, and he remained to the last a favorite with ladies.

He has had many followers in the Bohemian [artistic] way of life, few of whom have had his excuse. But nearly all of them ended in the same miserable, tragic manner.

Edgar Allan Poe Literature

- Alone

- Annabel Lee

- Black Cat (The)

- Dream Within Dream (A)

- Raven (The)

- Spirits of the Dead

- Sleeper (The)

- Valentine (A)