On this the last official day of the Wessex Hillforts and Habitats Project, we have reached the final of three hillfort imaginings crafted by illustrator Julia Lillo.

This last one is controversial.

Figsbury Ring in Wiltshire lies east of Salisbury on a high spur of land looking back towards the city.

A single, near circular rampart with an outer ditch with opposing causewayed entrances through the defences.

This place is wierd because about 20m inside the rampart there is a wide ditch. This also has opposing causeways in line with the gaps through the outer rampart. Particularly curious because this ditch has no bank….so where did the soil go.

There were excavations in the 1920s when Neolithic pottery was found in this ditch, early Iron Age pottery found in the outer rampart ditch and a scatter of Early Bronze Age pottery across the site. No real evidence of round houses or pits…but in 1704 a later Bronze Age, broken bronze sword was found.

So, a place used over 1000s of years… but not really a settlement it seems. A geophysical survey showed no features to indicate that it was permanently occupied. Curious…. how to illustrate that?

I remember large events held in the park in front of Kingston Lacy House. Tents everywhere with all sorts of displays inside… representing all the various activities across the twin estates of Corfe Castle and Kingston Lacy. Thousands visited over several days but archaeologically, once the tent pegs had been removed, nothing was left behind…. apart from the odd coin in the grass.

Hillforts were not all used in the same way, some were permanently occupied settlements but others were created perhaps as secure stock enclosures or temporary or seasonal meeting places and/or markets. Occasionally, they were perhaps built for a specific military campaign or other purpose and then abandoned or reoccupied and modified at a later date…

so many possibilities…. and if tested against the narrative records of the New Zealand Maori and their hillforts.. all the reasons for their existence listed above were true for various sites across the North and South Islands as narrated in their histories.

So.. there were animal burials in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. Horned ox skulls are sometimes found within layered structured deposits as sacred deposits filling disused grain storage pits… alongside the skeletons of other animals and the odd chunk of human body.. or whole person.

They were like us in some ways but in most aspects of their lives, particularly in their belief systems…..they were very different in their outlook.

Animal sacrifice was a big thing. The Iliad and the Odyssey are full of the details of offering bulls to the deities. The gods got angry and needed proper sacrificial offerings… if they were to work their power in support of the mortals.

Enter Figsbury and you are cut off from the surrounding landscape. You are contained and feel led into the centre through the inner ditch causeways. What happened in there?

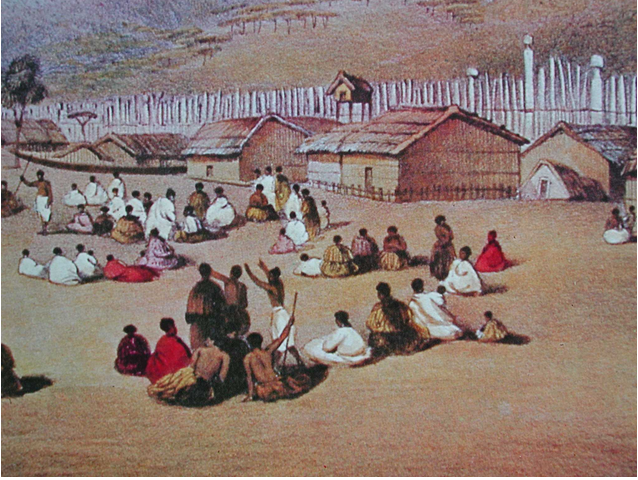

For this drawing, I did a sketch and asked for an imagining of ritual based on the Ancient Greek writings of Homer about 800 BC.

On the rampart a wooden palisade but decorated with carved posts and over the gate skulls fixed on gateposts.

It is a creative view of what might have happened here. It gives an idea of a different vision of the world.

There are so many things we may never know about these ancient communities. Most is a vague misty landscape with occasionally an archaeological shaft of sunlight to make things a little clearer.

In 1988 we excavated an ox burial dating to the Late Bronze Age deliberately buried in a deep inner ditch within an enclosure. We found two sheep burials nearby. Animal sacrifice was a thing. Whether it happened at Figsbury we may never know.

Look out for the Wessex Hillforts Booklet we’ll put a link to it on this blog when it is ready.