John drove me in the Land Cruiser along the unmetalled track. We were getting ever higher, Pinus Radiata stretched out below us as far as the eye could see.

A stony landscape.. of more angular slopes.. volcanic.. not like the smooth undulating downlands of home.

He parked in a forestry cutting in the trees, we took our cameras and began our climb through the dense foliage to the ridge top.

Back in the 30s, when they planted the trees, the woodsmen had written about some of the sites they came across. Today, we were going to rediscover one of these.

John turned and said. ‘In Maori this pa is known as blind man’s hill. People rarely come here now. There is a sense of tapu about this place..

He pushed past another branch and it flicked back.

‘Careful of your eyes Martin’ he said and intimated a sense of two worlds drawn together ….Maori and Pakeha. The first nation’s narrative of the landscape, all around, and particularly real, on this day, very far from anyone else…. in Northland’s Waipoua Forest

What an extraordinary job this was. To map the archaeology and to highlight the significant sites for protection… before the loggers moved in with their machines. Clearfelling the pine trees to take the crop.

The previous week, Jill and Kate had taken me north across the Rawene Ferry to 90 mile beach.. there to meet John and Gaby at Aupouri.

We had walked amongst the dunes and seen the huge middens of shells mixed with fish and occasional whale bones, the food debris from Maori coastal communities, abandoned a few hundred years ago.

Kate found a bright greenstone/jade pendant resting on the surface of one white heap.

In the evening, in honour of the midden makers, we collected tuatua shell fish and cooked them over a fire as the sun set over the Tasman Sea.

Most of my employment occurred deep within the pinelands or native bush, walking the forestry compartments, from the Waipoua river up to the valley edge.

I lived in a hut within the Forestry base. Each day, before setting out, I wrote the date and my destination and left it on the table (health and safety). Then out on the trail bike with a back pack and the map.

To be honest they hadn’t mapped it all in 1980. The contours stopped on a blank line and I had to rely on a few black and white aerial photos to plot my location.

So there I was, out amongst the trees and streams with a couple of fantails flitting from twig to twig, taking advantage of the insects I disturbed in my progress through the totara, rimu and nikau.

Aileen Fox had spotted the similarities. Though the Maoris had no pottery or metal, their hill top pa and kumara/sweet potato storage can be compared with Britain’s Iron Age hillforts and grain pits.

The Maori were great agriculturalists. Down by the river floodplain there were overgrown drainage channels and heaps of stone faced mounds for taro and kumara propagation. Higher up the valley, I would break through the trees onto a spur of land and find a string of playing card shaped pits and a couple of terraces for huts. These were for storage of their produce and the Victorian explorers drew the little pitched flax-roofed structures, constructed to keep the root vegetables frost-free and dry.

The Maori discoverers of New Zealand had brought the kumera by boat from warmer polynesian climes and they needed protection to flourish.

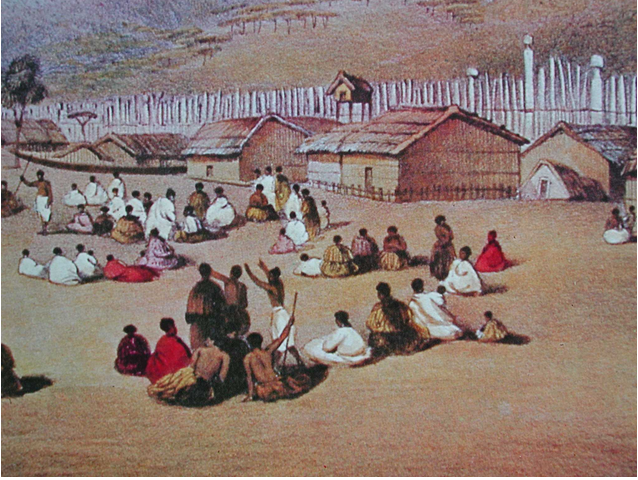

Then on the ridge tops, occasionally, a defended settlement or pa. Some had ramparts, many had a series of terraces, the outer enclosures defended by wooden palisades and within, a scatter of rectangular timber framed buildings.

What a shame we don’t have the sketches of Roman traders and soldiers to show us what Hod Hill, Hambledon or Badbury in Dorset would have looked like.

There are many early 19th century sketches surviving in Auckland library. It’s where I spent some time writing the survey report once I had returned to city life.

By the 1800s, the Maori had mixed their culture with the advantages and distresses of the Europeans. Muskets replaced the Meri and Patu and gun pits were dug into their hillforts.

So, over 40 years later, I often think of the Waipoua valley…. stumbling out of the forest onto the beach. The day we found glittering paua shells in the rock pools and the visit to the valley kainga settlement where the Maori foresters and their families lived above the home sites of their forefathers.

In imagination, my 90 mile beach is Studand, though you would need to go to Cleaval Point or Fitzworth on the north Purbeck shore to find the Iron Age cockle shell middens…

And for Waipoua, the angular and flat-topped hills of West Dorset. The pa sites of Pilsdon, Coney’s ….and particularly Lambert’s Castle.

Much of Lambert’s Hill is covered in trees and reminds me of that walk up with John to ‘Blind Man’s Hill’.

This week’s storms take me back to 1990 when some of Lambert’s trees tumbled and one tore up the rampart of the hillfort. Michael and I spent the summer cleaning up the section and drawing the layers making up the defensive bank and the silted outer ditch.

In West Dorset, the soil is acid like Waipoua; bone does not survive, and like the people of Northland, there was no pottery at Lambert’s, just the layers of sand and stone used to construct this high fort looking across to Golden Cap and the Channel, high above the Marshwood Vale.

Our only find, a 19th century beer bottle, probably tossed against the bank by someone celebrating at the annual Lambert’s Castle fair and horse racing event which continued there each year right up to the mid 20th century.

At Waipoua Kiwinui pa, we came across a single flake of jet black shiny obsidium, scuffed up from a forestry track.

As Kate held this exotic object, I thought of England and the worked flint, scattered across the fields of the chalklands many 1000s of miles away.

‘We ambulated these mountain tops for seven miles, when suddenly the deep valley of Waipoua opened to our view, in the centre of which a large native settlement appeared. The valley was irrigated with a stream of water. We had a mile still to walk before we reached the kainga, but were no sooner seen winding our way down the hills, than we could hear the distant shouts resound through the valley, and a distant discharge of muskets commenced to greet our arrival.’ J.S. Pollack, 1838