EUDORA WELTY

GUY DAVENPORT CELEBRATES A WRITER & PHOTOGRAPHER

Eudora Welty shares with Samuel Beckett the mastery of English prose among writers now living; she is one of the greatest of American writers in all our history, taking her place beside Hawthorne, Poe and O. Henry in the craft of the short story. She cannot be placed as a novenlist for the simple reason that her novels are unlike any written in the United States. We must turn to Faber and Joyce to find a family for them, and ultimately we must note that as the fulminator of a particular tradition in prose she is alone, a superb and triumphant artificer.

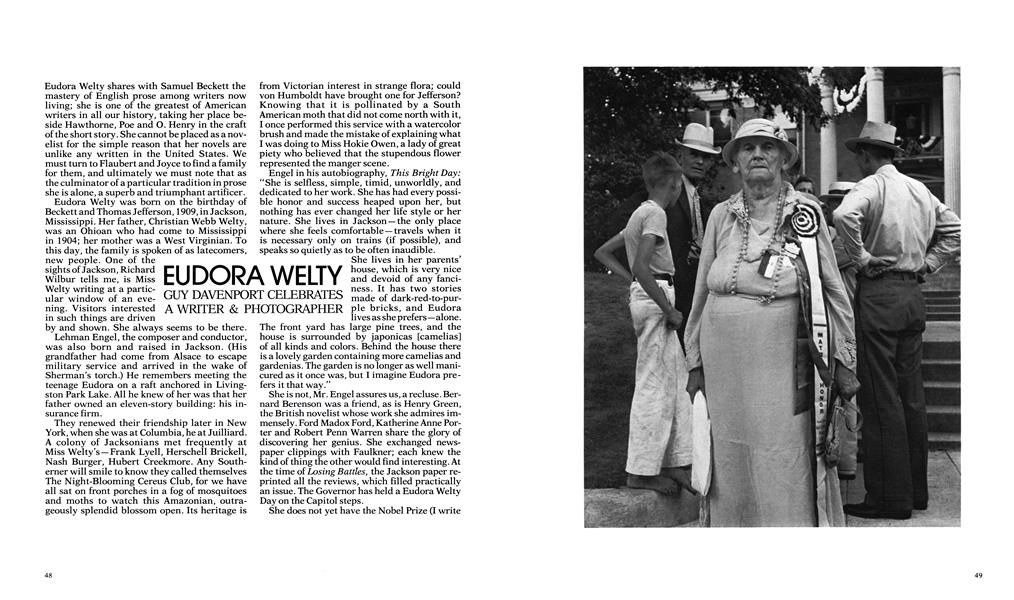

Eudora Welty was born on the birthday of Beckett and Thomas Jefferson, 1909, in Jackson, Mississippi. Her father, Christian Webb Welty, was an Ohioan who had come to Mississippi in 1904; her mother was a West Virginian. To this day, the family is spoken of as latecomers, new people. One of the sights of Jackson, Richard Wilbur tells me, is Miss Welty writing at a particular window of an evening. Visitors interested in such things are driven by and shown. She always seems to be there.

Lehman Engel, the composer and conductor, was also born and raised in Jackson. (His grandfather had come from Alsace to escape military service and arrived in the wake of Sherman's torch.) He remembers meeting the teenage Eudora on a raft anchored in Livingston Park Lake. All he knew of her was that her father owned an eleven-story building: his insurance firm.

They renewed their friendship later in New York, when she was at Columbia, he at Juilliard. A colony of Jacksonians met frequently at Miss Welty's —Frank Lyell, Herschell Brickell, Nash Burger, Hubert Creekmore. Any Southerner will smile to know they called themselves The Night-Blooming Cereus Club, for we have all sat on front porches in a fog of mosquitoes and moths to watch this Amazonian, outrageously splendid blossom open. Its heritage is from Victorian interest in strange flora; could von Humboldt have brought one for Jefferson? Knowing that it is pollinated by a South American moth that did not come north with it, I once performed this service with a watercolor brush and made the mistake of explaining what I was doing to Miss Hokie Owen, a lady of great piety who believed that the stupendous flower represented the manger scene.

Engel in his autobiography, This Bright Day: “She is selfless, simple, timid, unworldly, and dedicated to her work. She has had every possible honor and success heaped upon her, but nothing has ever changed her life style or her nature. She lives in Jackson —the only place where she feels comfortable — travels when it is necessary only on trains (if possible), and speaks so quietly as to be often inaudible.

She lives in her parents’ house, which is very nice and devoid of any fanciness. It has two stories made of dark-red-to-purple bricks, and Eudora lives as she prefers—alone.

The front yard has large pine trees, and the house is surrounded by japónicas [camelias] of all kinds and colors. Behind the house there is a lovely garden containing more camelias and gardenias. The garden is no longer as well manicured as it once was, but I imagine Eudora prefers it that way.”

She is not, Mr. Engel assures us, a recluse. Bernard Berenson was a friend, as is Henry Green, the British novelist whose work she admires immensely. Ford Madox Ford, Katherine Anne Porter and Robert Penn Warren share the glory of discovering her genius. She exchanged newspaper clippings with Faulkner; each knew the kind of thing the other would find interesting. At the time of Losing Battles, the Jackson paper reprinted all the reviews, which filled practically an issue. The Governor has held a Eudora Welty Day on the Capitol steps.

She does not yet have the Nobel Prize (I write them about that every year), though she is read by all Scandinavians, who buy her books with a dedication that shames our appreciation of her. The Encyclopaedia Britannica informs us she is the author of Clock Without Hands, a work which it omits, with admirable consistency, from the list of novels by Carson McCullers.

When, last summer, a tree that shaded the room in which she works was felled, she began closing the blinds against the glare of Mississippi noons. Promptly she got an anonymous letter. “Open those blinds, Eudora," it read. “We know you’re in there!"

If one were asked what absolute distinction makes Miss Welty's fiction or photography different, the answer would not be her alert, perfectly idiomatic, honest prose, nor her immense understanding of character, nor her transmutation of fact into universal symbol, but her unique study of inarticulateness.

Life happens at all times in a context we do not understand, and that most of our actions go unexplained among ourselves, and that when we do try to be articulate we usually talk about one thing while meaning another, is something we all know. Fiction or picturing, however, can usually be caught out ignoring this obvious truth. Flaubert began to acknowledge it, making a distinction between conscious and unconscious motives. Miss Welty takes it for granted that her characters cannot know their predicament, and that they are wanderers full of expectation for they know not what. We feel that there is wisdom in silence. It is difficult to say what the characters are up to, what they expected of each other, why they part as they do.

This is not to say that Miss Welty is inarticulate, or that she deliberately tells her stories ambiguously. She is most articulate, and her subject is the incoherent buzz of experience, the way we live.

Action is character, and character fate, but in Eudora Welty's fiction we are almost always invited to follow action without purpose, a busy idleness. She observes character when it is in the machinery of unsuspected forces. Hence the preponderance of rituals: funerals, weddings, meals, recitals, journeys. Action of the usual sort is of so little interest to Miss Welty that it pleases her to omit mention of motivations to which Balzac would devote pages.

The early stories tend to be about people who are unaware of what they are doing because of feeble-mindedness or invincible ignorance. Her characters are always locked into their worlds. This is sometimes, as with Uncle Daniel Ponder, whose innocence is inviolable, a blessing; sometimes comic, as with the narrator of “Why I Live at the P.O." But usually it is the context for Miss Welty's ironic observation. Character is the design of our boundaries.

Art is the attention we pay to the wholeness of the world. Ancient intuition went foraging after consistency. Religion, science and art are alike rooted in the faith that the world is of a piece, that something is common to all its diversity, and that if we knew enough we could see and give a name to its harmony. An anecdote about Faulkner has it that once on a spring evening he invited a woman to come with him in his automobile to see a bride in her wedding dress. He drove her over Mississippi back roads and eventually across a meadow, turning off his headlights and proceeding in darkness. At last he eased the car to a halt and said the bride was before them. He switched on the lights, whose brilliance fell full upon an apple tree in blossom. The sensibility that shaped that moment is of an age, at least, with civilization itself.

These photographs, recognizing that the soul looks out of the eyes unmasked and vulnerable in its nakedness, that the human face is its biography for the whole world to read, would be interesting enough for their compassion and beauty even if they weren't the sketch book of one of the greatest interpreters of the human heart.

We needed no extra evidence than the stories that Miss Welty's eyes are sharp, but it is a gift to have these photographs. One might plausibly print them with the stories as illustrations —

superfluous illustrations, to be sure, but then all illustrations are that. Henry James was the first author to balk at the illustration of novels, and when his publishers said that the public would not buy an unillustrated novel, he chose with genius to have the photographer Alfred Langdon Coburn make pictures of places: streets, houses, interiors. These would serve, he said, for tone.

Tone, flavor, sense of place. One of my teachers in England adored Miss Welty's writing and used to ask me about that world which he knew only from her work. What was a front-porch swing? A bottle tree? A chinaberry tree?

We have photographs of John Quincy Adams, but not Jefferson; of Alexander von Humboldt, but not Napoleon.The photograph was not merely a new kind of evidence for history, it was a radically different kind of evidence —a splitsecond record of eyesight, an externalization of a private and unique response of the body to light. It is the only art that has had to be appropriated to the human touch, for in itself it is mechanical, inhuman. Only da Vinci could make da Vinci’s brush do what it did; anybody can take a photograph. Anybody can also draw a bow across the strings of a fiddle. The harmony of skills that must go into the making of even so-so photographs is as great as that required for any art.

These pictures are of things just as they were when they were seen. True, here and there, the presence of the camera has caused a ripple on the surface of reality (an amused face, a sudden stiffening of the body into a pose), but not often. Look at the Claiborne County woman sitting on her porch. All Scotland looks at us from her eyes. One of her sons peers from inside the door, another through the window. A mother cat and two kittens repeat the triad of stalwart country folk in feline idiom. Both woman and cat have their limbs gathered to a strict symmetry. The house was built when line and volume spoke for something, a decorum, a belief; and the rocker says that they still do. Everything in the picture says continuity.

There is a quickness and boldness here that springs a firm sense of what a picture is. The eye that chose the moment and angle for "To Find Plums" has seen both Mary Cassatt and Gauguin. "Home, Ghost River Town" has Cézanne all over it. Whistler could not have found a better pose for the girl in "Sunday School Child."

And then there are the startling pictures that belong to the camera, and to accident, such as "Speaking in the Unknown Tongue," where the tilted horizon has given an ecstatic lurch to the world, and "Hypnotist, State Fair," where the spieler in cap and gown, striped anklets and bare legs just behind him, and sideshow posters clash with an incongruity the most assiduous Surrealist might envy.

The meaning of the world, said Wittgenstein, is outside the world. Events and values are distinguishable only in relation to others. A totality of events and values, the world itself, requires another. Hence our recourse to symbols which serve for a sense of otherness, and our inadequate ideas of time and death, of purpose and being. Into this inadequacy mankind introduced an imaginary world in which the elusive is made to stand still, and an order too extensive and complex to understand is given limit and measure.

The artist shows the world as if meaning were inherent in its particulars. We dress biological imperative in custom and ritual; the artist dresses it in analogy, and finds design in accident and rhythm in casualness. That every event is unique and every essence distinct from all others rarely interests the artist, for whom event is pattern and essence melodic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

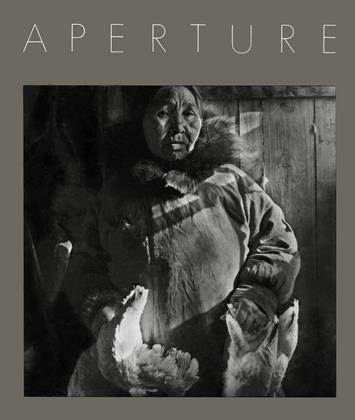

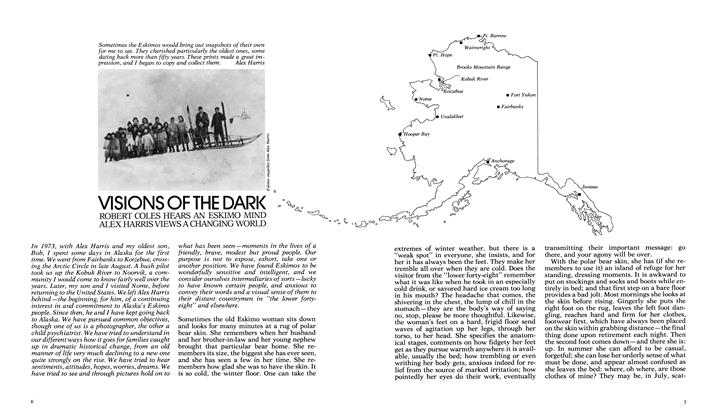

Visions Of The Dark

Spring 1978 -

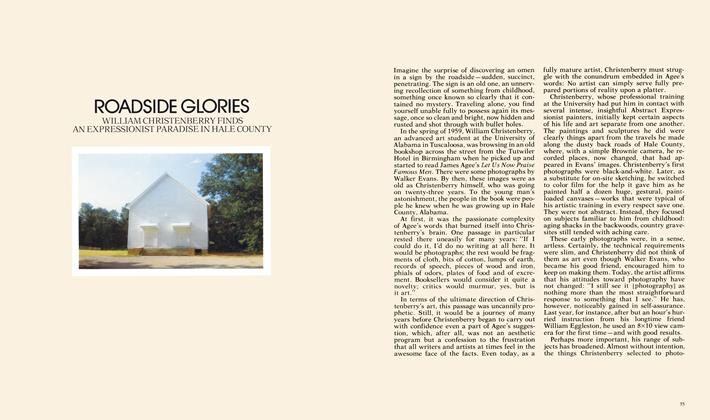

Roadside Glories

Spring 1978 By Benjamin Forgey -

The City's Lively Beat

Spring 1978 By Lloyd Fonvielle -

Inhabited Nature

Spring 1978 -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasMirrors And Windows: Messages From Moma

Spring 1978 By Jed Perl -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasLooking At Lange

Spring 1978 By Anita V. Mozley