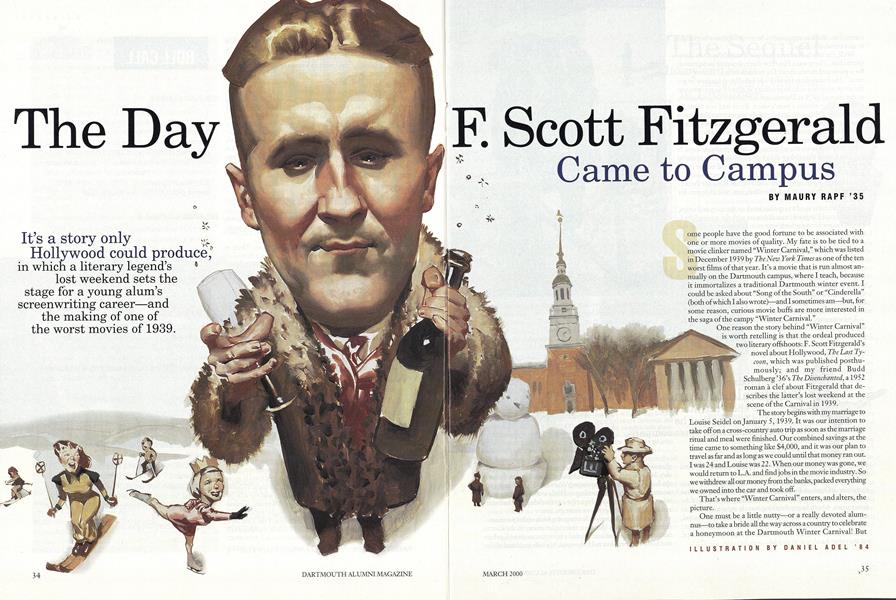

The Day F. Scott Fitzgerald Came to Campus

It’s a story only Hollywood produce.

MARCH 2000 MAURY RAPF ’35It’s a story only Hollywood produce.

MARCH 2000 MAURY RAPF ’35ome people have the good fortune to be associated with one or more movies of quality. My fate is to be tied to a movie clinker named "Winter Carnival," which was listed in December 1939 by The New York Times as one of the ten worst films of that year. It's a movie that is run almost annually on the Dartmouth campus, where I teach, because it immortalizes a traditional Dartmouth winter event. I could be asked about "Song of the South" or "Cinderella" (both of which I also wrote)—and I sometimes am—but, for some reason, curious movie buffs are more interested in the saga of the campy "Winter Carnival."

One reason the story behind "Winter Carnival" is worth retelling is that the ordeal produced two literary offshoots: F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel about Hollywood, The Last Tycoon. which was published posthumously; and my friend Budd Schulberg '36's The Disenchanted, a 1952 roman a clef about Fitzgerald that describes the latter's lost weekend at the scene of the Carnival in 1939.

The story begins with my marriage to Louise Seidel on January 5, 1939. It was our intention to take off on a cross-country auto trip as soon as the marriage ritual and meal were finished. Our combined savings at the time came to something like $4,000, and it was our plan to travel as far and as long as we could until that money ran out. I was 24 and Louise was 22. When our money was gone, we would return to L.A. and find jobs in the movie industry. So we withdrew all our money from the banks, packed everything we owned into the car and took off.

That's where "Winter Carnival" enters, and alters, the picture.

One must be a little nutty—or a really devoted alumnus—to take a bride all the way across a country to celebrate a honeymoon at the Dartmouth Winter Carnival! But remember, this was supposed to be no more than a beginning to an extended holiday.

Well, the trip to Hanover brought that holiday to an unexpected halt. There was a film crew there, shooting backgrounds for a proposed movie about Dartmouth called "Winter Carnival." I had envied my friend Budd Schulberg, because he got the script assignment from producer Walter Wanger, who was in the class of 1915 at Dartmouth but left before graduation.

Now, after almost a year's work, Budd had not come up with an acceptable story and certainly not a screenplay. It was clear that the action would take place against the Carnival background and that one character in the movie would be the editor of the daily college paper, if for no other reason than because Schulberg had been the editor in his undergraduate days. It was also known that if they didn't shoot background material at the February 1939 Carnival, the movie could not be made until February 1940. And Wanger had already put himself in a bind by signing an agreement with Warner Bros, for the services of their rising star Ann Sheridan, who would report for work in April.

Faced with the need to expedite work on the story and script, Wanger hired Fitzgerald to collaborate with the novice Schulherg. Wanger brought both writers to Hanover to soak up the Carnival atmosphere firsthand, to get started writing and to advise the film crew on which backgrounds to shoot. There is some reason to believe that Wanger hoped he would be rewarded with an honorary degree from the college he was about to immortalize, and that he brought Fitzgerald to Hanover to help that cause and to show the literati on the faculty that the producer traveled in high-class company. Indeed, he invited the entire English department to a cocktail party in the Hanover Inn to meet the celebrated literary figure now working for him—and I was there.

Unfortunately, Fitzgerald, who was known to be an alcoholic but who had been on the wagon for several months, had been given a send-off on the flight East with a well-intentioned but devastating bottle of champagne, and when the time came for Wanger's party, the illustrious writer made his entrance by falling down the stairs leading to the Hanover Inn lobby. And that was just the beginning.

He was sobered up a little to make the trek up Main Street to the site of Outdoor Evening, where the Carnival Queen was crowned. Later, Fitzgerald insisted on making the rounds of the fraternities, where heavy drinking was de rigueur. The man who celebrated decadent youth in the 1920s with his first novel, This Side of Paradise, felt very much at home with the decadent youth of the 1930s. His usefulness to Wanger and the script, on the other hand, was at an end.

Wanger fired both writers, and Schulberg took Fitzgerald to New York and placed him in a drying-out establishment on the East Side. Wanger then rehired Schulberg and asked him to contact me as a collaborator. (Wanger knew me from my Hollywood days and had recommended me for admission to Dartmouth.) At first I turned down the offer because I was, in fact, on my honeymoon and didn't want to go back to Hollywood.

Wanger then doubled his offer (I think it meant an increase from $100 to $200 a week) and said that Schulberg and I could stay in Hanover to work on the script. Wanger would be in New York for a couple ofweeks, and we could confer with him there. My Hollywood agent thought it was a great opportunity, and my new wife regarded a stay in Hanover as an extension of our holiday, so I accepted. Budd and I got adjoining rooms in the Hanover Inn and started work. At the end of the first week, Wanger got antsy and felt that we had to be in New York so he could confer with us everyday. He was staying at the Waldorf; he booked rooms for us at the less-deluxe (and less expensive) Warwick. Then Wanger announced that he was returning to Hollywood. Since we were now making progress on the script—even though we had written only about 20 pages—we must go, too.

I objected strenuously. He was going back on his promisefirst to let us work in Hanover, then to let us stay in the East to finish the script. I had interrupted a honeymoon to oblige him and had no place to live in Hollywood. My wife and I had all our belongings with us, including our car. He both threatened and cajoled. Where was my loyalty? I couldn'twalk off an assignment. As for the car, he would ship it to Hollywood and ship it back to New York when the job was finished. He would pay my wife's train fare and mine, of course, and pay for the two of us to return to New York when the job was over. We would be back where we were with more money in the bank. What could we lose? Little did we know!

My wife never forgot that train trip. Here we were, still on a honeymoon, and I spent all night, every night, in the drawing room adjoining ours, working with Schulberg on the screenplay. The only time I saw Louise was at meals, and then she had to listen to our talk about the idiotic affairs of our ex-Carnival Queen Jill Baxter and the renewal of Jill's romance with our idealization of a young college professor, who had time to chaperone fraternity parties and to officiate at Winter Carnival ski events.

After about five weeks in California, we had finished a screenplay, but we didn't like it very much and neither did Wanger. The trouble was, he had no suggestions for improvements. I did, but they would have required a complete rewrite, and Sheridan, the star, was due to come onboard in about two weeks. Then the expense meter began ticking at a fast rate. Wanger decided that I had to be replaced by someone who could write a shootable script in a hurry. He didn't want a masterpiece; he wanted something he could shoot.

By this time, all thoughts of going back to New York and resuming the holiday honeymoon were gone. We were deep into a new life in our rented house in Westwood Village. But Wanger fired me, and Schulberg told him that if I went, he would go, too. That brought forth the old bromide—"You can't walk off a job." Next came Wanger's twist—the zinger: "If you quit now, I'll see to it that you never work in Hollywood again." The threat was meaningless, and Budd knew it. Buthe stayed. The movie was made.

Afterwards, the tentative credits were sent out by Wanger's office. My name wasn't on them. I asked to read the final screenplay. I hated it, but it wasn't too different from the one Budd and I completed a few weeks before shooting. I called my agent for advice. "If you're entitled to credit, take it," he said. "It's a major film by a major producer and will be distributed by United Artists." "But it stinks," I said. "It doesn't matter," my agent said. "No one will remember. And you need the major credit. Take my word for it."

I did, and I ended up with joint story and screenplay credit. And my agent was wrong. People did remember, and after the film was released I couldn't get a job for four months. I'd go out on a job interview and everything would be going fine until I was about to leave. Then the producer would ask, "Didn't you work on 'Winter Carnival'?" My affirmative answer would kill the deal.

My agent would probably be right about the value of credits on most clinkers. But "Winter Carnival," as one of the worst movies of 1939, was something special. The fact that generations of Dartmouth undergraduates have enjoyed the movie as a midnight attraction on scores of subsequent Carnival weekends has helped to heal the wound to some extent, but I still cringe when a discriminating student asks somewhat incredulously after one of those midnight showings, "Didn't you work on 'Winter Carnival'?"

It's a story only Hollywood could produce, in which a literary legend's lost weekend sets the stage for a young alum's screenwriting career—and the making of one of the worst movies of 1939.

Producer Walter Wanger '15 (above in fur, conferring with Secretary of the College Sidney Hayward) turned Dartmouth into a movie set, complete with phony backdrops, local extras and a film crew at the base of the ski jump.

Budd Schulberg (right) whisked a drunk Fitzgerald back to New York before returning to Hanover and the screenplay. In the film, Richard Carlson and Ann Sheridan (far right) play a former college professor and an ex-duchess. The plot features her enjoying "an unexpected romance while visiting Darmouth's colorful winter carnival," according to studio publicity materials.

Reprinted from Back Lot: Growing Up With the Movies by Maurice Rapf(published 1999 by The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland) with permissionfrom the author.

The producer, an alum, brought Fitzgerald to Hanover to show the literati on the faculty that he traveled in high-class company.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

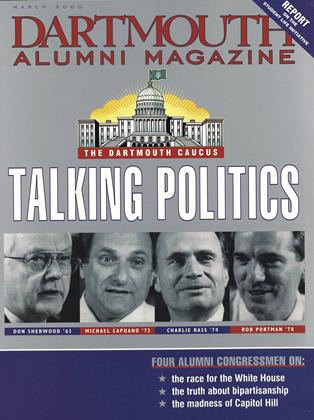

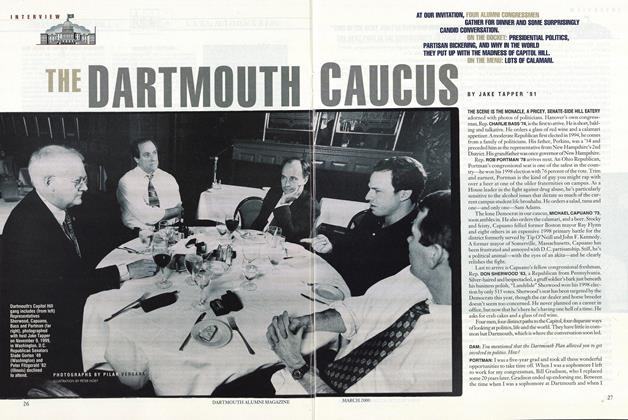

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

March 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureOne on One

March 2000 By Mel Allen -

Interview

InterviewPicture Perfect

March 2000 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

March 2000 By Noel Perrin -

Interview

Interview“Now We Have a Platform for Discussion”

March 2000 -

Presidential Range

Presidential RangeTaking Initiative

March 2000 By President James Wright

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

OCTOBER 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Rassias

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By HANSON W. BALDWIN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMoments of Peace

December 1995 By Stephen Madden -

Feature

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

OCTOBER 1994 By Varujan Boghosian -

Feature

FeatureGlory Days

NOVEMBER 1988 By Woody Klein '51