“It’s good to write like this, not sitting in a study but at the beach, in sunlight and wind. This is how Homer wrote, and Virgil too”

– Sándor Márai wrote in 1948, during his first year of his Italian emigration. Italy became one of the most important places in Sándor Márai’s life. As a young man he made several trips there, then, as an immigrant, lived in Italy for 17 years. What impact did this period of deliberate exile in Italy have on Sándor Márai’s life work? Who and what influenced this period of life and how? These questions will be discussed at the literature night, titled Márai’s Italy, in the Müpa on 25 September.

It is a cruel twist of fate that the writer who personified European culture, citizen identity, and humanism, lived in an era in which these were constantly under the threat of eradication. Márai, whose life mission was to write and think freely, had no choice but to leave his beloved country where the expanding communist dictatorship was reducing the freedom of speech for intellectuals day by day.

In August 1948, Sándor Márai, his wife Lola and their adopted child boarded a train and said goodbye to their homeland forever. They spent seven weeks in Switzerland and then travelled further to Italy.

“It’s a horrible world, everywhere I look, it’s just horrible. There is nothing left for me but Italy, and sometimes people, and books, poems, music. Wine. The sea. That’s all left for me. Everything else is horrible”

– Márai wrote in his Diary in 1951.

They stayed in Naples for four years, then moved across the sea to New York in 1952. In 1967, they returned to Europe again, this time to Salerno in southern Italy. From May 1980 until the author’s death, he lived in the US again, in San Diego.

During the first period of emigration to Italy, the Márai family settled in the Posillipo district of Naples. Lajos Marton, the uncle of Márai’s wife, bought them an old villa. This is the setting of one of Márai’s greatest novels, The Blood of San Gennaro. A man flees Soviet rule for Naples, where he hopes to find the last vestiges of European culture. The novel can also be read as a veiled self-confession, in which we understand why the writer was forced to leave his homeland and why he had to take voluntary exile.

From 1951, under the pseudonym Ulysses, Márai’s notes from Italy were read on Radio Free Europe, alongside his poem Funeral Sermon, also written during his years in Naples, which was the most influential poem of Hungarian emigration literature. The family’s financial situation is well described in this 1949 note by Márai:

“We are spending our last money; if we manage to sell the fur, we will live again for a month. I think of this when I listen to the news on the Budapest radio. It is still more pleasant to have one’s fur pulled off than one’s skin.”

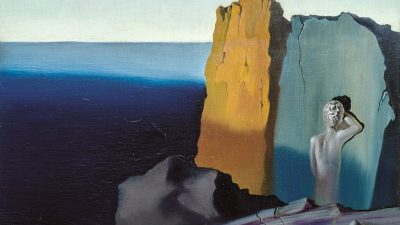

For Márai, the Naples Bay was the cradle and archaic guardian of Western civilisation he so feared from the savage destructive forces of the twentieth century.

“This rocky outcrop is like a hook, one of the twisting arches of an anchor. It was on this anchor that Ulysses’s ship was hung, the beginning of what would later be called Western civilisation.”

(The Complete Diary, 1950)

Since the early 1960s, the Márai family has been to the south of Italy several times, then they returned to live in Italy again in 1967, in a sixth-floor apartment in Salerno. In Italy, the most important thing for the writer, apart from the European cultural treasures, was the proximity of the sea. During his stay in Naples, he writes:

“Half an hour in the sea. For the 70th time this year. This is the best that life can give: the sea, this amniotic fluid.

(The Complete Diary, 1949)

The sea is refuge and safety, like the womb, and a purifying, vitalizing element for Márai.

“On the sea, I always feel a strange calm. Everything that is a problem or a doubt on land ceases to be one on the sea. This different homeland has different laws.”

(The Complete Diary, 1950)

Salerno offers the writer a sense of calm and arrival, with twelve volumes (including multiple editions) published during his productive years here.

The evening at Müpa Budapest in September will bring the atmosphere of Márai’s years in Italy to life with the participation of some of the most distinguished Márai scholars and experts on Italy, with many Márai texts and musical interludes. The prose passages in the programme also draw on the writer’s time in Italy. The round-table discussion will be moderated by Ágnes Ludmann, head teacher and workshop leader of the Italy Research Group at the József Eötvös Collegium, and will include renowned experts such as Antonio Sciacovelli, Márai’s translator and most important Italian researcher; Tibor Mészáros, literary historian and curator of the Márai legacy (Petőfi Literary Museum); and László Csorba, historian, former director of the Hungarian Academy in Rome, and director general of the Hungarian National Museum.

“The sea is dark blue. Naples is shining. Now, in the Easter light, the city shows its true face. There are few more beautiful cities in the world, few that are smarter, sadder, wiser. The “grey sea” is wise here too. In the morning – with Odysseus in my hand – I read and peered out the window. Like reading a guidebook in a foreign land.”

(The Complete Diary, 1949)

Article: Anna Zöllner

Translation: Zsófia Hacsek

Comments