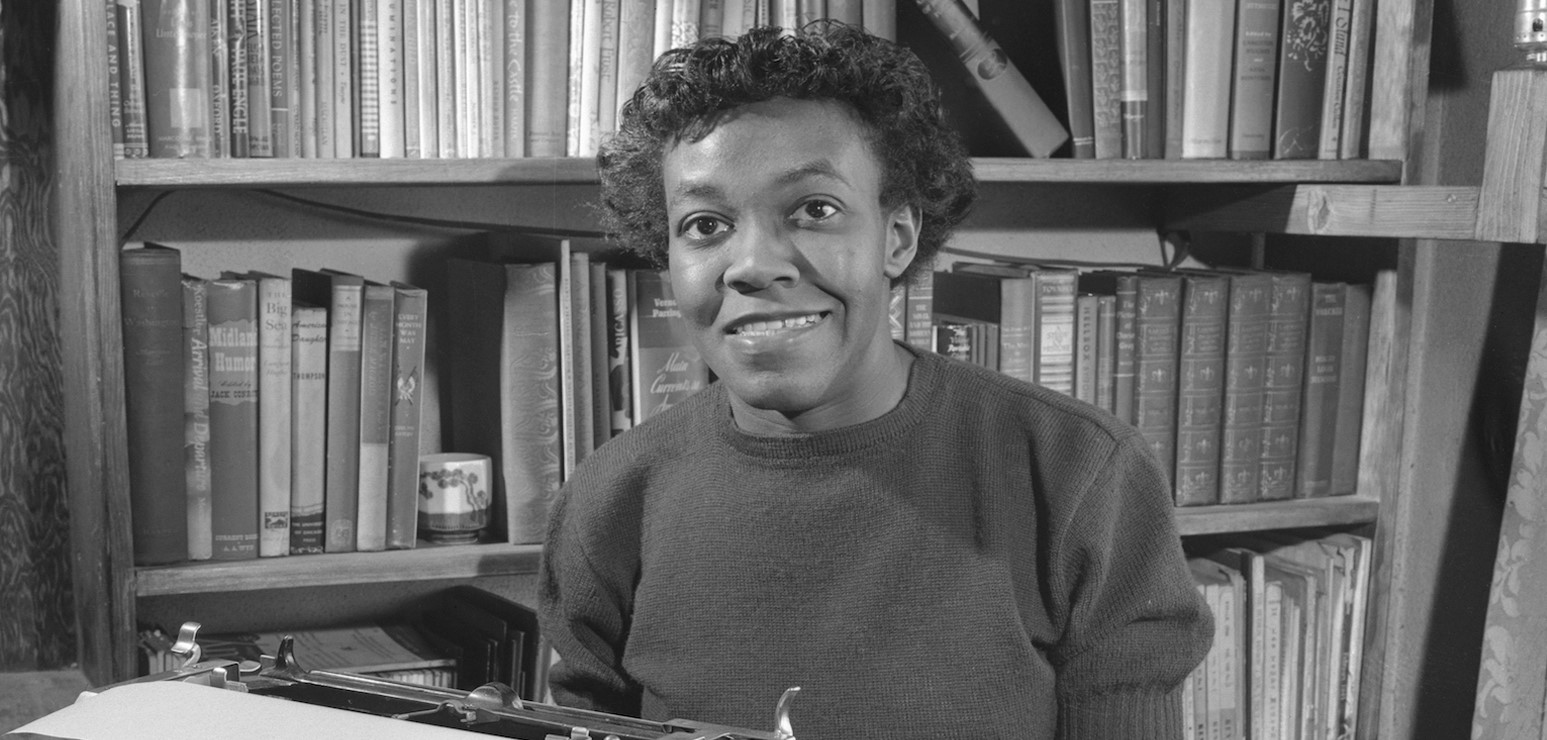

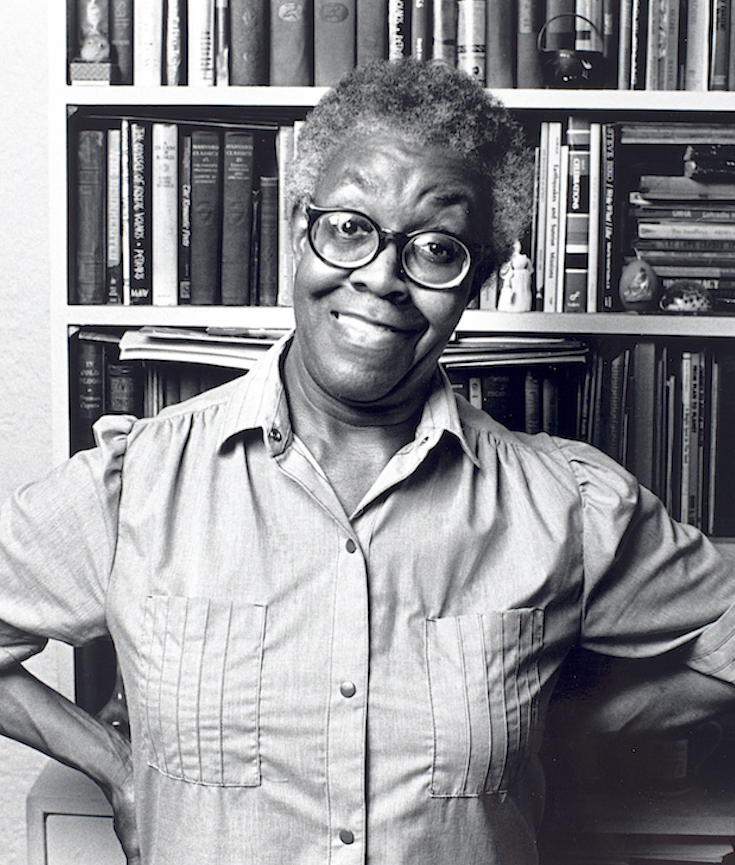

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) was a poet, novelist, and teacher who lived most of her life in the Bronzeville, Woodlawn, and Greater Grand Crossing neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. Her second poetry collection, Annie Allen, won the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, making her the first African American to win a Pulitzer in any category. She served as the Poet Laureate of Illinois from 1968 until her death in 2000, and as the United States Poet Laureate at the Library of Congress from 1985 to 1986.

Works

- A Street in Bronzeville (1945), a poetry collection

- Annie Allen (1949), a poetry collection (Pulitzer Prize)

- Maud Martha (1953), a novel

- Bronzeville Boys and Girls (1956), a children’s book

- The Bean Eaters (1960), a poetry collection

- Selected Poems (1963), an anthology of her first three collections

- In the Mecca (1968), a poetry collection

- For Illinois 1968: A Sesquicentennial Poem (1968)

- Riot (1969), a poetry collection

- Family Pictures (1970), a poetry collection

- Aloneness (1971), a children’s book

- Report from Part One (1972), an autobiography

- The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves (1975), a children’s book

- Beckonings (1975), a poetry collection

- To Disembark (1981), a poetry collection

- Mayor Harold Washington; and, Chicago, the I Will City (1983)

- The Near-Johannesburg Boy, and Other Poems (1987), a poetry collection

- Winnie (1988), a poetry collection

- Children Coming Home (1991), a poetry collection

- Report from Part Two (1996), an autobiography

- In Montgomery, and Other Poems (2003), a poetry collection

Biography

Early Years

Gwendolyn Brooks was born on June 7, 1917 in Topeka, Kansas, in the dining room of her grandparents’s home at 1311 North Kansas Avenue. Her parents had already moved to Chicago years earlier, but returned to Kansas for the birth. Gwendolyn’s father, David Brooks, was a janitor at McKinley Music Company. Her mother, Keziah Wims Brooks, was a teacher. From the age of four until she moved out as an adult, Gwendolyn lived with her parents and her brother Raymond at 4332 South Champlain Avenue in Bronzeville.

Brooks attended Forrestville Elementary School, Hyde Park Branch School, Wendell Phillips Academy, and graduated from Englewood High School in 1935. According to her diaries, she felt ostracized throughout her childhood and teenage years because her skin was darker than most of the popular girls. In her teens, she published dozens of poems in various outlets, including at least 75 poems in the Chicago Defender. She graduated from Woodrow Wilson Junior College in 1936.

After failing to get a job at the Chicago Defender thanks to Robert Abbott’s preference for light-skinned women (Jackson, 14), she went to work as an assistant to a spiritual advisor in the Mecca Flats for four months, an experience she would write about, decades later, in her fourth poetry collection, In the Mecca (1968).

In 1938, Brooks met her husband Henry Blakely Jr. (1916-1996) at the South Parkway Branch of the YWCA, where she attended the NAACP Youth Council alongside John H. Johnson and Margaret Taylor-Burroughs. Gwendolyn and Henry were married in 1939 and lived in a series of Bronzeville apartments. According to biographer Angela Jackson: “The first was a kitchenette in the Tyson building on Forty-Third and South Park; the second, a room at a Mrs. Sapp’s; the third, a kitchenette at 6424 S. Champlain, where their son, Henry III, or Hank, as he was called, was born on October 10, 1940. They then moved to a garage apartment at 5412 S. Indiana, followed by a mice-ridden kitchenette at 623 East Sixty-Third, under the clattering ‘L’ train, where they lived for seven years.”

Literary Career

In 1941, Brooks began attending Inez Cunningham Stark’s poetry workshops at the South Side Community Art Center at 3831 S. Michigan Avenue along with her husband and Margaret Taylor-Burroughs. In 1943, Stark encouraged Brooks to submit poems to a contest at the Midwestern Writers Conference at Northwestern University. Brooks won the competition, and an editor at Knopf in New York, Emily Morrison, sent her a request for more poems after reading her award-winning entry, but rejected the 40 poems Brooks sent in reply.

Brooks then sent 19 poems to Harper & Brothers in New York, where editor Elizabeth Lawrence asked Richard Wright to evaluate Brooks’s work. He loved it, and Harper & Brothers published Brooks’s debut collection, A Street in Bronzeville, on August 18, 1945. “It hit Afro-America with the force of an atomic bomb,” writes Brooks’s biographer, Angela Jackson. Most of its poems were based on Brooks’s daily lived experiences and observations on Chicago’s South Side.

Over the next few years, Brooks reviewed books for the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun-Times, and Negro Digest. In 1947, Harper rejected her poetry manuscript titled American Family Brown, which she would later repurpose for a novel, Maud Martha. But in 1949 it published her second collection, Annie Allen, about a young Chicago girl who comes of age throughout the book. The following year, Brooks and Annie Allen won the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, making her the first African American to win a Pulitzer in any category.

Brooks’s daughter, Nora Brooks Blakely, was born in 1951. In October of 1953, the family moved into a house at 7428 South Evans. In 1953, Harper published Brooks’s only novel, Maud Martha. Over the next few years, she worked on other fiction projects, including a sequel called The Rise of Maud Martha, but none were ever published in their entirety. In 1956, Harper published a collection of children’s poems alongside illustrations, Bronzeville Boys and Girls, though the original illustrations by Ronni Solbert were of white children.

In 1960, Harper published Brooks’s third collection of poetry, The Bean Eaters, from which some of her most-quoted and most-anthologized poems were excerpted in Poetry magazine, including “We Real Cool.” At this point in her career, Brooks became passionate about teaching. Roosevelt University rejected her teaching application because she didn’t have a college degree, but in 1962 she taught American literature at the University of Chicago, and from 1963 to 1969 she taught a poetry workshop at Columbia College Chicago. During this period, Harper published a best-of anthology of her previous work, Selected Poems (1963), as well as her fourth poetry collection, In the Mecca (1968), inspired by her time working in the Mecca Flats decades earlier. Also in 1968, she succeeded Carl Sandburg as the Poet Laureate of Illinois.

In the Mecca was her last book with Harper. After attending the Fisk Writers Conference of 1967, meeting Don Lee (later Haki R. Madhubuti), leading a poetry workshop out of her home for Blackstone Rangers, and becoming more involved in the Black Arts Movement, Brooks decided to support Black publishers with her future work. Broadside Press, a publishing company founded by Dudley Randall in Detroit, published Brooks’s next four books in quick succession: Riot (1969), a poetry collection; Family Pictures (1970), a poetry collection; Aloneness (1971), a children’s book; and Report from Part One (1972), the first half of her autobiography.

In 1969, Brooks and her husband Henry separated for a few years, but reunited in 1973, according to a notice in the Chicago Defender. Her brother, Raymond Brooks, died of natural causes at the age of 55 in 1974. Brooks also made several trips to Africa in the 70s, both alone and with Henry, including Kenya, Tanzania, and Ghana. A children’s book in 1975, The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, inspired by her daughter Nora’s Halloween costume, was her first published by Haki R. Madhubuti’s Third World Press in Chicago. In 1978, after a prolonged illness, Brooks’s mother, Keziah Wims Brooks, died at home at the age of 90.

Throughout the 1980s, Brooks traveled the country, supported Black presses and writers, and served as the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, an office which her biographer Angela Jackson says she “transformed.” After a frightening incident where her home was burglarized, Brooks and Henry moved into an apartment at 5530 South Shore Drive in Hyde Park in 1991.

In 1990, now in her 70s, Brooks began teaching at Chicago State University. Third World Press published the second volume of her autobiography, Report from Part Two, in 1996. That same year, her husband Henry died in his sleep at the age of 79. According to Angela Jackson, Brooks continued to give readings even after her booking agent passed away in 1998, all the way up until a month before her own death. On December 3, 2000, Brooks died from cancer in her home at the age of 83. Her funeral was held at the University of Chicago’s Rockefeller Chapel after heavy a snowfall. She was buried in Lincoln Cemetery alongside her mom and dad.

Links

- Gwendolyn Brooks’s obituary in The New York Times

Sources

- A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life and Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks by Angelica Jackson, Beacon Press, 2017.