The Diversity of Sacred Lands in Europe Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the Delos Initiative – Inari/Aanaar 2010 Edited by Josep-Maria Mallarach, Thymio Papayannis and Rauno Väisänen

The Diversity of Sacred Lands in Europe Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the Delos Initiative

The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services, The Delos Initiative or other participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services, The Delos Initiative or other participating organisations. This publication has been made possible by funding from the Ministry of the Environment, Finland, and Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services. Published by:

IUCN, Gland, Switzerland in collaboration with Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services, Vantaa, Finland.

Copyright:

© 2012 All authors for their respective contributions, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, and Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services.

Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged.

Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder.

Citation:

Mallarach, J.-M., Papayannis, T. and Väisänen, R. (eds) (2012). The Diversity of Sacred Lands in Europe: Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the Delos Initiative – Inari/Aanaar 2010. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and Vantaa, Finland: Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services. 292 pp.

ISBN: 978-2-8317-1423-3 Cover photos:

Clockwise from the top: Fadil Sarki, Mikael Hintze/Metsähallitus, Knut Helskog, G. Porter, sanniopropone.com, Heiki Maiberg, Ervin Ruci/FunkMonk, Thymio Papayannis and Sebastian Cataniou in the middle. Back: Riina Tervo/Metsähallitus.

Layout by:

Taittotalo PrintOne, Minna Komppa

Translation:

PasaNet Oy, Spencer Allman

Coordinaton and Liisa Nikula, Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services text editing: Produced by:

Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services

Printed by:

Edita Prima Oy

Available from: IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Publications Services Rue Mauverney 28 1196 Gland Switzerland Tel +41 22 999 0000 Fax +41 22 999 0002 books@iucn.org www.iucn.org/publications Med-INA 23, Voukourestiu Street 106 71 Athens Greece Tel +30 210 360 0711 Fax +30 210 362 9338 secretariat@med-ina.org www.med-ina.org The text of this book is printed on Galerie Art Silk 130 gsm made from wood fibre from well-managed forests certified in accordance with the rules of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

The Diversity of Sacred Lands in Europe Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the Delos Initiative

Inari/Aanaar, Finland, 1-3 July 2010 Edited by Jose-Maria Mallarach, Thymio Papayannis and Rauno Väisänen

table of contents 7

All creation groans and sighs… Kari Mäkinen

15

Introduction to the proceedings of the third workshop of the Delos Initiative in Inari/Aanaar, Lapland, Finland Josep-Maria Mallarach, Thymio Papayannis and Rauno Väisänen

25

Part One: The Sámi people and their relation to nature

27

Greetings from the Saami Parliament Juvvá Lemet – Klemetti Näkkäläjärvi

33

Words of welcome Tarmo Jomppanen

37

Indigenous Sámi religion: General considerations about relationships Jelena Porsanger

47

Archaeology of sieidi stones. Excavating sacred places Tiina Äikäs

59

Part Two: Ancient, indigenous and minority sacred natural sites

61

Conserving sacred natural sites in Estonia Ahto Kaasik

75

Use and reuse of ancient sacred places in Mikytai, Žemaitija National Park, NW Lithuania Vykintas Vaitkevičius

85

Zilais kalns – Blue Hill in Latvia Juris Urtaˉns

95

Alevi-Bektashi communities in south-eastern Europe: spiritual heritage and environmental consciousness Irini Lyratzaki

109

Part Three: Managing lands of mainstream religions

111

The cultural and spiritual sites of the Parco Nazionale della Majella, Italy Vita de Waal

125

Holy Island of Lindisfarne and the modern relevance of Celtic ‘Nature Saints’. Robert Wild

139

Landscape linkages between cultural and spiritual values. The wetland of Colfiorito and the Lauretana pilgrimage route in the Plestian Plateaus. Chiara Serenelli

155

Part Four: Managing lands of monastic communities

157

Monastic communities and nature conservation: Overview of positive trends and best practices in Europe and the Middle East Josep-Maria Mallarach

175

Managing the heritage of Mt Athos Thymio Papayannis

189

Special Nature Reserve Milesevka and the Mileseva Monastery Nadezda Pesic, Svetlana Dingarac and Dimitrije Pesic

203

Part Five: Europe: a wealth of sacred natural sites

205

Diversity of sacred lands and meanings in Northern Europe: Challenges for the managers of protected areas Rauno Väisänen

217

The Carpathian Mountains, a realm of Sacred Natural Sites Sebastian Cătănoiu

231

The ‘sacredness’ of natural sites and their recovery: Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair McIntosh

245

Synergies between spiritual and natural heritage for habitat conservation in the Barents Euro-Arctic Region Alexander N. Davydov

259

Part Six: Other related issues

260

Applicability of the IUCN-UNESCO Guidelines for Protected Area Managers on Sacred Natural Sites: first assessment Josep-Maria Mallarach

271

Inputs and comments from the workshop

275 Conclusions 285 Appendices 291

The ecological footprint of the Delos Proceedings

All creation groans and sighs... Humanity and borders In the Finnish language, the early semantic strata associated with the concept of pyhä (’holy’) relate to a place on the landscape. The reference is to a border. Many place names, such as Pyhäjärvi or Pyhäjoki, bear this out. These are particular places in the wild, as far as which people have been permitted to travel, though no further. Holy outlines an area belonging to man – demarcates it. The word in this sense is still valid today, although it is no longer literally associated with a place on the landscape. When we speak of the ‘holy’ we are still expressing the idea of the borders of human existence. A holy day (for example Sunday) or holy object signifies a spiritual terrain isolated from others that speaks of somewhere beyond, a place that does not belong to man. It is a border which demands that we step back – we have to pause, just as we do at a geographical one. It requires our humility, sensitivity and respect. A sense of the holy and its protection are essential if people are to understand who they are. To be human is to stand before what is holy and to relate to it. That is the only way we can identify the borders of humanity and human activity.

Holy spaces are the doors to the meaning of everything The Christian interpretation of life is not detached from these archaic, distant meanings of the Finnish word pyhä - holy – but actually relates to them. This is the case with the stories of creation in the beginning of the Bible, which are basic depictions of human existence. They even use imagery that recalls the ancient meanings of the word. In the beginning, according to the stories, man is part of the same reality in which God is walking in cool of the afternoon. The holy is not somewhere on the outside. The world does not exist by chance but by the will of God. All creation is holy, because it reflects the holiness of its Creator. But man’s tragic destiny is to become separated from this, to be expelled from God’s garden. As is well known, it happens in the account of the Fall, the apple and the serpent acting as its agents. Its core meaning is that man will rise to the position of God and above everything else. The stories describe the basis of existence. Man is totally dependent on his Creator and creation, and his relationship with these is the most fundamental of all. It is a relationship with what is holy. The relationship is not simple or calm; it is contradictory, broken.

7

It is for this very reason - because of the hubris that shatters the basic relationship - that man needs to be able to identify and interpret the holy and those symbols that denote its reality: there is something more, something beyond our reality. The separately defined spaces, times and places that are recognised as holy are those that allow people, and the whole of creation, to breathe out, groan and sigh and create something new. They are doors to the deep meaning of life.

Does the holy have a place in modern-day living? From the perspective of those first stories, we might ask how in today’s western culture a person can understand his or her existence in relation to what is holy. As the foundations of the ecological system shake, there are good arguments for saying that God plays no part in our culture. The basic dimension of human existence, a sense of the holy, is absent, and in its place are merciless consumerism and the logic of exploitation. Where God is absent, people and nature only have a utility value, and no other. Nevertheless, we should not succumb to romantic ideas about history and claim that people used to have a sense of what was holy but now God is conspicuous by his absence. The modernisation of western culture has not buried the holy, but its place has changed. In the western process of modernisation, what was understood as holy broke loose from the authoritative power structure. Gradually, one had to get used to the notion that the holy was worshipped totally differently from the way in which power was worshipped. It was a liberating process. For the Christian Church, this legacy means that, living amidst the social and economic powers that are destroying mankind, we are called on to question radically what is going on and boldly stand up for human life itself. In the same process of modernisation, culture and society also became differentiated and fragmented. Politics, art, science, economics, business, education, religion all became their own separate areas of life. The area of religion became the reservation in which God was given a place to live. Talk of God and the holy was restricted to that place only. When religious life came to have a monopoly on the holy, as it were, other aspects of life could carry on as if they had no relationship to the holy or as if the borders of the existence of what was holy and of human activity did not concern them.

8

The borders of science In two areas of life, this has been particularly clear to see. One is the scientific/ technological domain. Within its framework, western man has approached life as if there were no borders on the landscape, thus permitting him to go as far as his knowledge and ability allow. In the areas of biomedicine, genetic engineering and virtual technology, we are at present in unknown territory. Here for once we have to ask whether there is a sacred border beyond which we may not go. The old maps provide no help. It is for this very reason that we need humility, sensitivity and respect so much, and they stem from an awareness of human borders and what is holy. This is a special challenge for Christian theology of creation. The challenge is on an altogether different scale compared to the conflicts between Christian belief and the natural sciences that date back to the 19th century. Now it is of fundamental importance to ask whether the borders of mankind are marked by anything more than intelligence and ambition. Should we be going on a voyage of discovery in all areas, or are there borders that cannot be crossed from the perspective of humanity and life, borders at which we have to stop, just like we do when we encounter the holy?

The borders of economics, business and consumerism The other area is economics and business. They now dominate our culture. It is on their terms that we decide what is important and what is not. Within this sphere of influence, the basic relations of human existence are shaped in a whole new way. How someone relates to economic activity is crucial. People are seen to be fundamentally dependent on it. It has a surplus value, with some features of the holy, but it does not point beyond mankind. One’s relationship with it is not the same as that with the holy or God, which indicates something outside man. There is of course room for God, but the limits of human activity or existence are not seen through Him, but through the economy. In the current climate, there is a danger that the holy, and symbols denoting the holy, will simply become a commodity, like everything else. There will be products that people acquire in order to experience what is holy. There is some demand for this, because a need for the sacred lies deep within a person, just like the desire to live. But, at the same time, the holy ceases to be holy. It becomes banal and metamorphoses into a momentary experience. It no longer allows us to identify human borders and territory. If people are primarily understood in relation to economic activity, the whole field of human endeavour is in danger of being perceived as one of market relations, pro9

duction, consumption, buying and selling. Then a person also comes to be seen as a product in the social and financial markets. Man, like creation, ceases to be valuable in himself, as something created, in a relationship with his Creator. The borders of humanity are then those of the market, and there is nothing beyond them. If the sense of what is holy disappears from our culture, so does the perspective from which human endeavour, mankind’s own territory, can be examined. This is the danger of a culture ruled by market ideology and consumerism. The consequences could be fateful. They are already visible in the area of global environmental issues as well as in the shape of the growing worldwide gap between the survivors and those who are left to rely on their own luck. This affects the poorest part of the world the hardest, although those who brought about the situation are the rich industrialised countries.

Where the holy places and spaces are It is in this western world, absorbed as it is by scientific/technological culture and consumerism, that we have a need for holy areas, a need to raise their profile and protect them, and not just have them safely placed within religion’s conventional realm. Holy places and spaces are places to stop at. They are places for calm and silence. Silence is the domain of the holy; it is God’s domain. When you can use words to sell anything and they lose their meaning, there is a need to turn to silence, to arrive at the real borders of human existence. The holy shuns the limelight, words and communication: it lives beyond them, where things are left unsaid - there are no words. Silence and stillness are the key ingredients of the Christian tradition, when everything stops before God. They are the essence of prayer. Finns get very close to this when they feel like turning their backs on everything that seems fulfilling in their daily lives but appears to conceal what is fundamentally true, and so they retreat to the seashore or the depths of the forest. There where you believe that you can breathe the presence of God. It is a genuine desire to acknowledge those fundamental relationships that have been put in place for man, the created being, and to see mankind’s place from the most basic of perspectives. The legacy of taking one’s time, silence and stopping represents an attitude to life of someone that is calm, takes deep breaths and submits to prayer. Thus, like other religions, the Christian Church takes on the task of maintaining a counterculture, amid all the efficiency, speed and cost-effectiveness of the modern world. In the silence, we also need to listen carefully to the voices of the limnologists, meteorologists and many other natural scientists, as well as the environmental move-

10

ment. Their intention is the same as that of the prophets in the Old Testament, who reminded us of our basic relationship with the reality of God and its distortion. Those voices radically compel us to confront the fact that there are limits beyond which mankind should not pass. They call for humility when contemplating creation; they tell us to stop at the border of the holy. On the European scene, where creation groans under the burden of weighty tarmac, there are signs that what is holy has not vanished. Even in the midst of everything, there is a constant dialogue with God. We have church buildings as a sign of this. Inside the churches, such pointless and unproductive activities as religious services go on. They do not have any particular appeal, and are given no public attention. The markets ignore them. Nonetheless, perhaps precisely because of them, a cultural place on the landscape remains open, somewhere people take stock of the fundamental relationships associated with their existence and want to bow their heads, as they do when they are before something holy. When people bow their heads before God in church, this is also a matter of confession: admitting that we cannot listen to the tragic sigh of creation as outside observers. We are deeply involved, even the Christian Church. As human beings, we are part of the consumer culture that contaminates everything, and, as Christians, we have interpreted our faith in such a manner that it has made way for the arrogant exploitation of creation. The Church cannot, and is unwilling to, dictate from on high how people should behave: instead, it invites them to common self-reflection, humility and the courage to change. In the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church’s Climate Programme, this invitation can be summarised in just three words: gratitude, respect and moderation.

Courage The Church’s approach derives from those fundamental stories about what is holy that are told in church services. Alongside the first stories in the Bible, another tale is told, one that gives another view of what is holy. It is the story of Christ, the central theme of the New Testament. It highlights the fact that the sacred, the reality of God, is not just beyond this reality, beyond the gates in God’s own domain, but is also fragmented radically amid humanity as a whole. The holy is not encountered solely in something that reflects the identity of something from the outside, something else that is purer and more whole. It can also be found wherever people have suffered loss, been victims, lost their way, lost their identity or been broken.

11

That is why this is not just about awareness and identification of the holy depending on humility and respect amid the reality that surrounds us. They also form a basis for the courage to stand up for all life at its weakest and most fractured points. ¤¤¤ The articles in this book highlight the notion of creation groaning, something that comes from different parts of Europe, their nature conservation sites, sacred areas and the life of prayer pursued in monasteries. It is the sound of an awareness of what is holy, inviting us to act with humility before creation and, at the same time, boldly resist the greedy world of business economy and the consumer culture. The articles, written by specialists, give a picture of a world we all share, where man is bound to creation, inseparably and fatefully. The worlds of different cultures and faiths have not shown a desire to withdraw or stay silent when it comes to acknowledging the responsibility we all have for creation. Europe’s holy places and traditions of prayer are powerful voices that call on us all to be determined and unyielding in our defence of what is holy in life. To this groan, this call, and on behalf of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, I would like to add these words from Psalm 104: “When you send your Spirit, they are created, and you renew the face of the ground.”

Kari Mäkinen Archbishop

Pielpajärvi Wilderness Church in Inari. > 12

13

14

Introduction to the proceedings of the third workshop of the Delos Initiative in Inari/Aanaar, Lapland, Finland Josep-Maria Mallarach, Thymio Papayannis and Rauno Väisänen

In order to provide to the reader with an introduction to the Proceedings of the third workshop of the Delos Initiative, it seems fitting, first, to present a short overview of what this Initiative is about, its goals, approach and accomplishments, and next, to discuss the purpose of the workshop, the reason for holding it in Northern Lapland, its development and programme.

The Delos Initiative: purpose, approach and accomplishments

itual values, the Delos Initiative was launched in 2004 in the framework of the Task Force on Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Areas of IUCN World Commission of Protected Areas. The Initiative was named after the Aegean island of Delos, a sacred site for both Greeks and Romans, dedicated to Apollo, the god of light, which was the centre of a long lasting Athenian Alliance. In ancient Greek the name Delos means ‘towards the light’. Delos Island has no links to any single living faith.

To contribute to improve the conservation of sacred natural sites (SNS) in developed countries and thus to assist in maintaining both their natural and spir-

The purpose of the Delos Initiative is to identify the pertinence and meaning of sacred natural sites and to investigate how spiritual values can contribute to

< Dwarf Cornel (Cornus suecica) 15

the conservation and wise use of natural areas in developed countries. The sacred natural sites in developing countries have received relatively much less public and scientific attention, e.g. by the IUCN/WCPA Task Force on Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Areas (Wild and McLeod, 2008). The Delos Initiative was born to remind and recognise that such sacred natural sites exist also in many protected areas of the technologically developed countries, though often neglected or overlooked, and that they are facing specific challenges and need action, if we are to conserve their heritage for the future. The Delos Initiative approach is mainly based on the standardised analysis of specific sites, chosen based on the criteria of relevance and representativeness. The idea is that if best practices can be identified and developed in highly significant sacred natural sites, these practices will easily spread to other sites by means of their different layers of radiance. The case studies chosen may either be important for world religions, the local or folk variations of them, or for the spiritual traditions of indigenous people or local communities. Case studies are carefully analysed, usually by local experts, with the objective to assess their natural, cultural and spiritual values, to understand their specificities, how they are related to each other, what are their main stakeholders, often different for the different dimensions of the heritage, and also to identify threats and opportuni16

ties for improvement. The draft diagnose is discussed with various local stakeholders, so that a deeper comprehension of the issues could be achieved. Then, a certain number of recommendations is proposed to overcome the main issues identified, hopefully after discussion and consensus with the main stakeholders again. The results of this process are presented to a peer group and debated among its members, so that lessons of general interest can be extracted from them. In parallel, theoretical work is carried out to understand the basic principles that the spiritual tradition has about the symbolic character of nature and in the sacredness of natural spiritual manifestations. At this level, the Delos Initiative attempts to assess their relevance and influence in various contexts and to propose and validate analogies and potential relationships. These two approaches and the implementation of the lessons they provide have brought forward positive results for the conservation of sacred natural sites, in particular, as well as for nature in general in several countries. Current case studies of the Delos InitiaÂtive include protected areas from virtually all IUCN management categories of protected areas. They are found in Europe, North America, Africa, Asia and Oceania, and related to the largest world religions and several primal spiritual traditions and folk religions. Most of these cases combine outstanding natural, cultural and spiritual values. All these sacred natural sites

have preceded the establishment of protected areas, often by several centuries, sometimes by thousands of years, and many of them have traditional custodians or guardians. Some are known by small communities, and have restrictions for access to outsiders, whilst others receive large numbers of pilgrims or visitors, numbering several million per year. The Delos Initiative has previously held two workshops, the first one at the holy mountain of Montserrat, Catalonia, Spain in 2006, and the second at Ouranoupolis, next to the monastic republic of Mount Athos, Greece, in 2007. The work carried out during the first years was compiled in the proceedings of both workshops (Mallarach and Papayannis, 2007; Papayannis and Mallarach eds, 2010) and encapsulated in the Montserrat (2006) and Ouranoupolis Statements (2007). Thus, the purpose of organising the third Delos workshop in Inari in Finnish Lapland, in the Sámi homeland, was to bring in the Northern European dimension and, especially, and to familiarise with the culture of the indigenous Sámi people. The conclusions of the work that has been done are being further evaluated and refined, so that guidance can be provided, initially to the managers of protected natural areas that include sacred sites, but which can also be of use to the custodians of these sites, and other concerned stakeholders. Specific Guidelines for sacred natural sites related to mainstream religions is a need recognised in the IUCN-UNESCO Guidelines

for Protected Area Managers on Sacred Natural Sites (Wild and McLeod, 2008), given that the existing guidelines focus on the sacred natural sites of indigenous and local communities. Until the present day, most of the work of the Delos Initiative has been developed in Europe, either at bioregional or national levels, together with organisations such as the IUCN Landscape Task Force, the EUROPARC Federation, Eurosite, the Convention of the Carpathian Protected Areas, Mediterranean Ramsar sites, and the Protected Area Unit of the Romanian National Forest Administration (Romsilva). For instance, the Spanish Section of Europarc agreed to integrate the cultural and spiritual values in the planning and management of protected areas in the Programme of Work for. Protected Areas of Spain 2009-13 (EUROPARC España, 2009), and currently specific guidance is being develop at the national level. Another example was the first Conference of the Carpathian Convention on Protected Areas in Romania in 2008, which approved the identification and characterisation of the Carpathian cultural identity in the protected areas, including spiritual, cultural and natural values, in the Programme of Work, and established a working group for the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of protected areas.

The Inari workshop The third workshop of the Delos Initiative was held in Inari, Lapland, Finland, from 30 June to 4 July 2010. The theme 17

of the workshop was: Diversity of sacred lands in Europe. The workshop was organised and supported by the Natural Heritage Services of Metsähallitus, the Ministry of the Environment and the IUCN National Committee of Finland. The workshop was attended by 30 participants from 14 countries: Estonia, Finland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Greece, Norway, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom, including both expert members of the Delos Initiative and observers from Finland and Russia. This third workshop featured a higher number of case studies than the two previous workshops, including many that were highly significant themselves and/ or to widen the representativeness. The location A short explanation of the place names is also in place. The venue of the workshop is Inari in Finnish. Inari is called Aanaar in Inari Sámi, Anár in North Sámi and Aanar in Skolt Sámi. Inari’s

name in Swedish, Finland’s second official national language is Enare. Inari is a Finnish Sámi village and the Sámi administrative centre that has roughly the same area of the old siida, located at the shores of Lake Inari. The word siida, meaning Lapp village, was the basic unit of the Sámi community, consisting of single family units or extended families. Each siida had a clearly defined area. (Näkkäläjärvi, 2002). Inari is situated some 300 kilometres of north of the Arctic Circle, in the northern part of Lapland. Traditionally, the Inari Sámi have been fishermen, hunters and gatherers (Lehtola, 2000). Nowadays, the traditional livelihoods are still important, but the Inari Sámi are mainly employed in similar occupations as the Finns. The significance of Inari is multiple for the Sámi people. For many centuries this was the ‘land of the three kings’ of Sweden, Norway and Russia, an important trade post located at the crossroads (Lehtola, 2000). It is for this

Participants of the Delos3 Workshop visiting the outdoor section of the Sámi Museum.

18

unique position in Northern Lapland that Inari is the only village of Finland where three Sámi languages coexist, i.e. North Sámi, Inari Sámi and Skolt Sámi. Significant efforts are being done both by the Sámi communities and authorities and by the Finnish government to preserve this rich heritage in face of the pressures of standardisation and globalisation (Aikio, 2000). Moreover, Inari is the closest village to one of the most important ancient Sámi sacred natural sites: Ukonsaari, i.e. the island of Ukko/Äijih, the ancient divinity of the thunder. This relevant sacred natural site was presented as a case study at the workshop held in Montserrat, Spain, in 2006 (Norokorpi and Ojanlatva, 2007). The venue of the workshop was the auditorium of Siida - The Sámi Museum and Nature Centre which is the interpretation centre for the culture and the environment in Northern Lapland. This remarkable facility opened its doors in 1998, after long years of preparation involving numerous Sámi researchers. It was a milestone for the Sámi people, and their self-esteem, as well as an outstanding facility that provides one of the best exhibitions about the Sámi life and its relations to nature and the northern environment. The Northern countries Many people of the North, including the Sámi are not very willing to speak about spiritual matters, not because they are not significant to them, but because they are considered very personal, private and sacred. This is a quite common

attitude in cultures with consistent shamanistic backgrounds, which are mainly based on experiences, supported by oral tradition, and have little, if any, written records, and very limited development of theology and philosophy. Studies conducted during the last few years showed that most visitors are attracted to protected areas of Finland, and also to other Scandinavian countries, not only to view or observe nature (plants, animals, landscapes), but also to have an experience of peace, harmony, grandeur, etc. showing that, even in those highly secularised countries, the immaterial values of nature continue to be highly significant for modern societies. It is possible that this kind of attitude is also hidden in the spiritual motivation of many nature conservationists, although it may be covered by the science language and piles of technical data. The programme The workshop began on Thursday with the welcoming speeches of Rauno Väisänen, Director of Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services of Finland; Tarmo Jomppanen, Director of the Sámi Museum; and Klemetti Näkkäläjärvi, President of the Saami Parliament. These initial speeches were not polite formalities, but conveyed important political and ethical messages, and for this reason they have been included verbatim. This was followed by a session devoted to the Sámi people and their rela19

tion to nature. Jelena Porsanger began with an exploration about the Sámi religion and concept of nature; Tiina Äikäs explained the results of the excavations conducted in sacred sites of Lapland (sieidi), raising a significant discussion about the ethical implications and the ways how the ethical principles were taken into consideration during the research and afterwards.

Kalns (Blue hill) in the context of other ancient cult sites of Semigallia, Latvia, featuring a remarkable ancient holy natural site which is considered a national symbol by Latvian people, with a relevant record of actions for conservation, despite many pressures and impacts, and also a recent complex used for the rituals of followers of old Latvian traditions and neo-pagans.

The afternoon session was devoted to native and indigenous sacred lands. It featured three presentations. The first, by Ahto Kaasik, talked about the Estonian national strategy for SNS protection and the challenges for conserving the sacred hill of Hiiemägi. Next, Vykintas Vaitkevičius presented the Žemaitija National Park and the ancient sacred places of Mikytai, Lithuania. The last presentation, the only one from overseas, was about the Mayo Lands and indigenous communities, Mexico, by Bas Verschuuren.

The second session focussed on the management of sacred lands by mainstream churches. It featured three presentations. First, Vita de Waal presented an overview of the extraordinary number and diversity of sacred natural sites at the Parco Nazionale della Majella, Italy, from prehistoric times to the present. Next, Rob Wild presented the case study of the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, one of Britain’s foremost Christian Sacred Natural Sites, the only one where national ecological values overlap with national religious and historical values, discussing the revival of the Celtic Christian spirituality and the role of nature saints in it. Finally, Chiara Serenelli presented a landscape approach to the wetland of Colfiorito, a Ramsar site connected with the Via Lauretana, an old pilgrimage trail in Italy discussing the role that landscape planning has and may have on the conservation and restoration of the key heritage elements that make this site precious.

On Friday, the first session was devoted to minority faiths in European countries and safeguarding natural and spiritual heritage. It featured a presentation about the little known Alevi-Bektashi Muslim communities found in Greece, Albania, Bulgaria and Turkey, by Irini Lyratzaki. The next presentation, on Uvac-Milesevka Special Nature Reserve and Mileseva Monastery, Serbia, by Svetlana Dindarac, discussed the rich and complex reality of an outstanding sacred natural site located in the holy region of Raska, the heart of old Serbia, and the current revival of its religious significance. Thirdly, Juris Urtaˉ ns, presented the Zilais 20

The third session focussed on the management of monastic communities. Thymio Papayannis presented an update about the preparation of an integrated management study for Mount Athos,

Greece, the only monastic republic of the world, in accordance with World Heritage Site Committee requirements. Next, Josep-Maria Mallarach made an overview presentation on the best practices and new trends on the management of monastic lands in Europe and Middle Eastern countries, summarizing a sixteen-century-old experience of community management which is still alive and vibrant in many countries. On Saturday, the first session was devoted to explore the diversity of sacred natural sites in Europe, including three presentations. The first dealt with the amazing diversity and number of sacred natural sites found in the Carpathian Mountains, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Serbia, by Sebastian Catanoiu. The second, with the recovery of sacred sites in Scotland, by Alastair McIntosh, where the author, through personal eloquent histories stressed the need to enter into a dynamic relationship with Sacred Natural Sites to become more fully alive, participating in the responsibility to conserve and reactivate them, as part of spirituality of resurrection; of that which gives life as love made manifest. The last presentation, by Alexander Davydov, was also an overview of a variety of Orthodox Christian and indigenous sacred sites in the Barents Euro-Arctic Region, including the most northern regions of Russia, Finland, Sweden and Norway. The two last sessions were not devoted to more case studies but to discuss and assess the validation of the 2008 IUCN-UNESCO Guidelines for Protect-

ed Area Managers of Sacred Natural Sites. This exercise allowed the active engagement of all the participants before and during the workshop. In the first session the work was carried in three parallel working groups, whilst in the second one the results of the three groups were presented and discussed, allowing the drawing of joint conclusions. Despite its limitations, this first attempt of assessing the applicability of the existing Guidelines for Sacred Natural Sites was an interesting learning exercise. The concluding session was a lively discussion in order to identify the key points that were to be included in the Inari/Aanaar Statement, which was refined during the next few days, until it reached consensus. The workshop included a guided visit to Siida - The Sรกmi Museum and Nature Centre, which features the evolution of the Sรกmi communities in this harsh but beautiful environment, their crafts and tools. In one of the rooms there was a temporary display of traditional Sรกmi drums, painted with symbolic designs and motives. There was also a visit to the open air museum, which features a good sample of different types of log homes and buildings that have been used in the Sรกmi area. In addition, an interesting field visit was organised, with two parts, enjoying a sunny afternoon. The first part, by boat, took the participants to Lake Inari, sailing to the Ukonsaari/ร ijih Island, where there were some interesting discussions about the need to set 21

limits to accessibility. The uniqueness of this ancient sacred natural site was made more apparent, as it were, thanks to the beautiful afternoon light and gorgeous views of the lake shores. The second part of the field trip, included a lovely walk through a wilderness area, from Pielpavuono Fjord to Pielpajärvi Wilderness Church, following a fairy-tale landscape of ancient forests, scattered with different types of wetlands. Once at the wilderness church, a wooden building dating from 1760, Vicar Arto Seppänen gave a speech to the participants on the relation of the Sámi and the Lutheran Church. Finally, after the last dinner in the Hotel Inarin Kultahovi a local cultural programme, including traditional Sámi yoik singing was offered to the participants. The co-ordinators of the Delos Initiative want to express their profound gratitude to the Finnish Saami Parliament

and to the Natural Heritage Services of Metsähallitus for hosting the Workshop in Inari, with the support of the Ministry of Environment and the IUCN National Committee of Finland, and contributing with the Delos co-ordination to the organisation of the workshop. In particular, they are especially pleased by the excellent involvement of the Natural Heritage Services, the national agency in charge of protected areas, including the participation of the Director of the Natural Heritage Services to the entire workshop, as well as to the editing of the proceedings. Finally, the three editors want to thank for the effective coordination and the careful linguistic review done by Liisa Nikula, Metsähallitus Natural Heritage Services, which succeeded in producing a good quality English publication from manuscripts of very diverse quality.

Rock on the path to Pielpajärvi Wilderness Church

22

References Aikio, A. (2000). The geographical and sociolinguistic situation, pp. 34-40, in J. Pennanen and K. Näkkäläjärvi (Editors) (2003) SIIDDASTALLAN - From Lapp Communities to Modern Sámi Life. Siida Sámi Museum (Inari). EUROPARC España (2009). Programa de trabajo para las Áreas Protegidas 20092013. Ed. Fungobe, Madrid. Lehtola, T. (2000). The history of the Sámi of Inari, pp.122-137, in J. Pennanen and K. Nakkäläjärvi (Editors) (2003) SIIDDASTALLAN -From Lapp Communities to Modern Sámi Life. Siida Sámi Museum (Inari). Mallarach, J.-M. and Papayannis, T. (2007). Nature and spirituality in protected areas: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop of the Delos Initiative. Mallarach, T. Sant Joan les Fonts, Spain: Abadia de Montserrat and IUCN. Näkkäläjärvi, K. (2003). The siida, or Sámi village, as the basis of community life. pp. 114-121, in J. Pennanen and K. Näkkäläjärvi (Editors) (2003) SIIDDASTALLAN - From Lapp Communities to Modern Sámi Life. Siida Sámi Museum (Inari). Papayannis, T. & Mallarach, J-M, eds. (2009). The Sacred Dimension of Protected Areas: Proceedings of the Second Workshop of the Delos Initiative - Ouranoupolis 2007 IUCN; Athens, Greece: Med-INA. Verschuuren, B; Wild, R; McNeely, J & Oviedo, G. (2010). Sacred Natural sites. Conserving Nature and Culture. Earthscan, London And New York. Wild, R. & McLeod, C. (Editors). (2008). Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected Area Managers. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; Paris, France: UNESCO, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series, 16.

23

Part One:

The Sรกmi people and their relation to nature

25

26

Greetings from the Saami Parliament Juvvá Lemet – Klemetti Näkkäläjärvi

The Constitution of Finland guarantees for the Saami the status of an indigenous people, the right to their own language and culture. The constitution grants Saami people cultural autonomy in Northern Finland in their homeland, which covers the municipalities of Enontekiö, Inari and Utsjoki and the northern part of Sodankylä. The Saami Language Act protects the language, and the responsibilities of the Saami Parliament are specially set by law. The Saami are the only indigenous people in European Union. In Finland there are three Saami languages spoken: the North, Inari and Skolt Saami. All of the languages are spoken

in Inari municipality. There are around 9300 Saamis living in Finland. There are also Saami people living in Norway, Sweden and Russia and all together there are ca. 70 000 – 100 000 Saamis. The traditional Saami livelihoods are reindeer herding, fishing, hunting, gathering and Saami handicrafts, Sámi Duodji. The only viable traditional livelihood is reindeer herding. Hunting and fishing have become secondary livelihoods. An important part of the Saami culture is the knowledge embedded in the language on places, nature, flora and fauna and the community’s history. The Saami musical tradition, yoik, is an important part of our culture and the

< The President of the Saami Parliament participated in the Seminar and wished all the participants welcome to Sápmi. 27

yoik transmits the oral tradition to future generations. Although all the Saami people live in villages, attend Finnish schools and many are occupied outside traditional Saami livelihoods, the Saami culture’s traditions are still very much alive. The Saami society is facing threats. Over sixty percent of the Saami in Finland are living outside the traditional Saami homeland and as many as 70% of the Saami children are living outside the Saami homeland. For the future of the Saami culture the situation is threatening. The Saami living outside the Saami homeland do not get education in the Saami language and culture with a few exceptions. The connection to the Saami traditions and the traditional Saami livelihoods weaken when living outside the Saami homeland. The Finnish Saami Parliament was established in 1995. There are Saami Parliaments in Norway and Sweden as well. The Saami Parliament is a political organ. Every four year 21 Saami are elected to the Saami Parliament. The Saami Parliament mainly works by giving statements, and by negotiating with officials. All the time the Parliament is trying to improve the legal status of the Saami. It also provides funding for services provided in the Saami language in the social and health sector, to Saami organisations and culture, and for the production of learning materials in the Saami language. The Saami Parliament has an office in Inari and side offices in Enontekiö and Utsjoki. There are around 30 people working in the Saami Parliament. A new Saami Cultural Cen28

tre is under construction in Inari. It is called Sajos and it should be completed in 2012. The building will also house the Saami Parliament and offer other services as well. The Saami Parliament was very happy that the third Delos Workshop was organised in the Saami homeland and especially in Inari, which is a home of the three Saami cultures. The Áddjá, Ukko in Finnish, is probably the most wellknown Saami sieidi in Finland. The sieidi is a sacred place for the Saami people. A sieidi is usually a natural object that is usually of stone and unshaped by human. Sacred sites and the meanings associated with them are a part of the ethnic identity of the Saami, and they have played a role in the creation of the Saami environmental relationship. Sieidis are evidence of social organisation and of a process of getting a grip of the environment of the surrounding reality. Sieidis have functioned as part of the Saami people’s environmental relationship. When asking the sieidi, for example, for help in hunting or fishing, it is important that the sieidi as well will be offered respect and benefit through sacrifice. The people and the Gods had mutual respect; and the Saami people would not try to control the force of nature or Gods at all. The Saami have offered usually meat, fish, antlers, metal and coins to the sieidi. Áddjá has been a sacred place for the Aanaar Saami people during centuries. Àddjá is a perfect Delos case study site. Inari municipality is planning on having a lot of tourist attractions and resort villages built around

Lake Inari. Some of them are planned to be built near Áddjá. For the Saami people this development is unwelcome. It’s important that the religious site and its surrounding environment are protected from mass tourism. The Saami traditional religion, shamanism has evolved together with the Saami culture and livelihoods. Nature is an important part of the Saami shamanistic religion. The Saami attitude towards nature can be described as an attitude of unity, in other words, man is seen as a part of nature, not as holding power over it. The Saami religion that has helped the Saami people to survive in nature has almost disappeared. When the colonialists came to the Saami area, the Saami religion was rapidly forbidden and also the traditions linked to shamanism disappeared. The Saami people were forced to abandon their religion and convert to Christianity. Our knowledge of the Saami religion is thin, because the oral tradition was lost. And, that is something that no science can bring back. Luckily, at least sieidis and their meaning have survived through the assimilation process. Although shamanism was replaced by Christianity, the sieidis continue to be an important part of the Saami cultural heritage, and knowledge of the sieidis has been passed on from one generation to the other. Many of the Saami sieidis are well known. However, there are still many sieidis that are only known by members of the community. The Saami people have wanted to

keep the knowledge private, and the privacy of the Saami people’s spiritual beliefs has to be respected. In recent years there has been quite a lot of discussion on who can study sacred sites of the indigenous people, who should benefit from the studies and how the research should be conducted. The approval of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 is meaningful when considering guidance on how to conduct research in sacred sites. The Declaration states in article 11 that ‘indigenous peoples have the right to practice and revitalise their cultural traditions and customs. It includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artifacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature’. Furthermore, article 12 states that ‘indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practice, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains’. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is a powerful document and it obligates different stakeholders to respect the spiritual beliefs and places of indigenous peoples. I hope that the Declaration will be implemented in Finland and in other countries as well. 29

For researchers and indigenous people, it is important that common guidelines are set on how sacred sites of indigenous people should be studied. Finland, like all of the other European Union Countries, has ratified the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. For indigenous people the Convention is highly important. Article 8(j) of the Convention protects the traditional know ledge of Saami linked in natural resources. Finland has begun the implementation of Article 8(j) of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The purpose of the work is to secure the safeguarding of the traditional Saami knowledge. The working group will complete its work in summer 2011. The Saami expect that the proposals to be made by the working group will help safeguard the traditional Saami knowledge. A code of ethical conduct was approved in the Conference of the Parties

to the Convention on Biological Diversity in autumn 2010. The code gives guidance when working in areas where indigenous people are inhabited, where their traditional areas are located or in connection to their sacred sites. When studying indigenous cultures and their heritage, it is important to take the research ethics into serious consideration. For indigenous people it is especially important that they can approve the research methods and aims, and be aware of the research results. The code of ethical conduct states that the information obtained from the research with indigenous people should be shared with them in understandable and culturally appropriate formats, with a view to promote inter-cultural exchanges, knowledge and technology transfer. Perhaps in future the Delos Initiative should consider these aspects as well.

Drum at SĂĄmi Museum. > 30

31

32

Words of welcome Tarmo Jomppanen

The Sámi Museum Siida was founded as early as in 1959, and it opened for the public for the first time on Midsummer Day in 1963. For more than three decades, the Museum was a facility that stayed open only during the summer. Today, the Open-Air Museum hosts almost 50 original Sámi buildings and constructions, as well as relevant reconstructions, and it still constitutes a popular part of the exhibitions that Siida provides to the public on the Sámi culture and northern nature. In 1998, when the new Siida Building was completed, the Sámi Museum became a facility that was able to run professionally. At the beginning of 1999, the Finnish Ministry of Education granted the Sámi Museum Siida the status of a national special museum. During the past

12 years, the museum assumed an increasing number of new and diversified tasks. The Sámi Museum has launched regional activities in the Sámi Area: in Western Lapland in Hetta in the municipality of Enontekiö and in Eastern Lapland in Sevettijärvi, which is the centre of the Skolt Sámi culture. Our third regional office will be established in a few years time at the Ailigas Institute in Utsjoki in the northern part of the Sámi Area. The Sámi Museum Siida aims at developing the activities of the museum so that it will take care of the tasks dealing with the Sámi in the museum field. As the cultural institutions of the Sámi are very young, this will, in practice, require a redistribution of the resources and the recording and documentation responsibilities. 33

At present, the Sámi Museum Siida is already responsible for collecting and recording the material cultural heritage of the Sámi related to historic times. The National Museum of Finland does not expand its Sámi collections anymore, and there has been an agreement with the Provincial Museum of Lapland that the Sámi Museum bears the main responsibility in this sphere. At the moment, the Sámi Museum has not reached a final solution on how to divide the responsibilities of managing the prehistoric cultural heritage and cultural landscapes, but it is proceeding towards an agreement. The entire Sámi Area, or Sámi Homeland, can be considered a Sámi cultural landscape. This wide region still has a great number of areas that have not been surveyed, as well as many cultural monuments and sites that have not been registered yet. The number of archaeological inventory surveys conducted in the Sámi Area is small when compared to the number of such surveys carried out elsewhere in Finland. As a result of mining, the infrastructure necessitated by tourism and the economic use of forests, the pressures on land use in Lapland have increased. To survey the area archaeologically, we need both expertise and more resources than we have now.

What is a Sámi cultural environment? In the Sámi community, the terms ‘cultural environment’ and ‘cultural land34

scape’ are understood more comprehensively than in the case of traditional cultural landscapes. The cultural landscape of the Sámi consists of an environment built by people, but also of immaterial, symbolic culture created by people. Such a cultural environment includes, for example, the communal knowledge of the right to use certain areas and routes, place names, stories, yoiking, beliefs and narratives – and a vocabulary in the native language which makes communication on these issues possible. Understanding this necessity is extremely important, especially when the management and protection of the cultural environment and heritage of the Sámi are concerned. It is also crucial to remember that, in terms of culture, the Sámi Area is not homogenous. From the point of view of cultural environments, there are differences in natural conditions and sources of livelihood; the Sámi groups are also different in terms of their visual cultures, cultural contacts, belief traditions, customs and languages. Until now, tasks that deal with Sámi cultural environments have mainly been taken care of through relevant projects. During the inventory project, a clear need for a permanent Sámi cultural environment unit became evident. The mapping of the Sámi cultural heritage and the cultural environments related to it must be an ongoing process. There are a great number of cultural environments in our area that are

threatened. It is extremely important to locate the sites which no longer show any visual signs of use, but which we know that are still there according to narrative tradition. One of the characteristics of the Sámi cultural environments is that the old way of living and moving did not necessary leave traces in nature – therefore, the natural surroundings of many cultural sites look completely untouched. For years, the founding of a Sámi Cultural Environment Unit has been one of the most important goals of the Sámi Museum. The Finnish Sámi Parliament, too, has been very active in this regard, supporting the establishment of such a unit in its statements to different authorities. We have now taken a step forward in this matter, as a three-year pilot project called Sámi Cultural Environments will be launched at the beginning of 2011. As the name suggests, the project will carry out activities that deal with Sámi cultural environments. The Sámi Museum Foundation has been granted EU funding for 2.5 years by the Regional Council of Lapland for a project called Ealli biras – Elävä ympäristö (‘Living Environment’). One of the objectives of the project is to draw up a Sámi Cultural Environment Programme for the Sámi Area. The project will employ a coordinator with expertise in Sámi cultural environments. Through special funding from the Min-

istry of Education, the project will also engage an archaeologist. The Cultural Environment Unit will operate under the auspices of the Sámi Museum Siida. It has already been agreed that during the pilot project, the National Board of Antiquities will delegate tasks concerning the management and protection of cultural environments to this office. In Finland, the National Board of Antiquities has so far made similar agreements with a number of provincial museums. Another objective of the pilot project is to draw up an operations model for the Sámi Cultural Environment Unit together with the Sámi Parliament, the National Board of Antiquities, the Ministry of Education and the Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY) in Lapland. Our goal is to ensure permanent funding for the Cultural Environment Unit so that its activities will be carried out on a permanent basis from the beginning of 2014 onwards. I would like to welcome the Delos Workshop here in the midst of a Sámi cultural landscape, which has been influenced by all the three different Sámi cultures and ways of life that coexist in the municipality of Inari: the Inari Sámi, the Skolt Sámi and the North Sámi cultures.

35

36

Indigenous Sámi religion: General considerations about relationships Jelena Porsanger

The indigenous religion of the Sámi people displays the relationship between humans and everything in creation, which can be called by the concept of ‘Nature’. This close relationship has traditionally been reciprocal, and can be considered as the very basis of the indigenous Sámi religion.

Indigenous Sámi religion Indigenous religion is a frequently used concept in the history of religion nowadays (see Harvey, 2000, 2002; Olupona, 2004). The concept includes religions that do not have a historical origin, such as Christianity, Islam, Buddhism or other world religions, and that

do not belong to any of the so-called revivalist movements. The concept of indigenous religion points to the original starting point of a religion, its persistent nature and a distinctive tradition which is characteristic for a particular people, alongside an ongoing process of change. In the history of research, terms and concepts like ‘the historical religions of literary cultures’ (Pentikäinen 1998) or ‘literary religions’ have been used to describe the world religions, while the concept of ‘indigenous religions’ represents religions which have been practiced by peoples mostly without a tradition of writing, e.g. Rydving (1993, 1995) and Braun and McCutcheon, 2000).

< Drum at Sámi Museum. 37

The concept of indigenous religions is used in Asia, America, Africa, Oceania, Australia and other parts of the world, where indigenous people are found practicing their own religion. The first part of the term ‘indigenous religion’ points to the original belonging of a religion. ‘Home’ or ‘belonging to a home place’ are connotations for the term indigenous. This concept leads to the notion of being produced or living naturally in a particular region in geographical, ethnic, or religious sense (Long 2004, 89). Present day researchers of religions have abandoned such terms as ‘primitive’, ‘pre-Christian’, ‘heathen’, ‘illiterate’ and ‘oral’. Academic religious research has traditionally focussed on issues that were quite distant from those that indigenous peoples themselves considered as indigenous religion. In connection with the Sámi indigenous religion, a sample of abandoned descriptive terms would include the following terms: ‘the Lapps’ idolarity’, ‘witchcraft and superstitions’, ‘the Lapps’ religion’, ‘the earlier Sámi heathen belief and superstitions’, ‘the original or ‘primitive’ heathen religion of the Lapps’ or ‘Sámi Pre-Christian Religion’ (Rydving (1993, 1995). These concepts are no longer in use. For the study of the Sámi spiritual culture in the Sámi language, using a Sámi approach, a new Sámi term has been proposed - sámi eamioskkoldat (in the North Sámi language, see Porsanger 2007). The concept of the Sámi indigenous religion emphasises the connection between the spiritual heritage 38

and the ongoing process of change in the spiritual life of the Sámi people, the central importance of the elders and ancestors as the carriers and teachers of the Sámi traditions, as well as embodying an inseparable unification of people and nature.

The concept of nature The Sámi have traditionally had a different notion of nature than, for example, urban people. The Sámi concept of nature implies relationships, reciprocity, and a notion of power, both for humans and for the whole surrounding world. There is no one single Sámi word, which is equivalent to the Western concept of nature. Instead, there is a variety of terms for what the Sámi considered as nature. That is why the term nature is used in this text in quotation marks. For nature one can find, for example, in North Sámi, the term of luondu, which implies the character of somebody or something, like beatnaga luondu ‘the nature of a dog’, olbmo luondu ‘character of a human’, luonddubiras ‘surrounding environment’ etc. The term meahcci implies territories and recourses outside peoples’ permanent living places, but there is a diversity of meanings of this concept (Schanche, 2002). Nature traditionally has been for the Sámi both a physical and spiritual entity, and humans are a natural part of it. For the Sámi, nature represents at the same time a home, a way of life, the source of survival, continuity and oral history, the present and the future. Tra-

ditionally, the aim of the Sámi people has not been to make the most efficient use of the natural resources as a source of income, but rather to use them rationally in a sustainable way, as survival in the North depends on the renewal of the riches of nature. The values and norms regarding nature that the Sámi learn already as children are especially crucial today both for the Sámi themselves and for the world, in general. Many indigenous peoples nowadays bring forward their values and understandings of their relationships with the natural environment. They emphasise that holistic understanding of the relationships practised by many indigenous peoples can teach the world a lesson about sustainability, balance and respect in the time of climate change and environmental problems. The Sámi have traditionally had a holistic understanding of relationships with nature. This can be exemplified by the concept of ‘maintenance of life’, used in the daily language by the North Sámi nowadays. This is a concept of birgejupmi, which is associated with people (both individuals and collectives), natural resources, physical, spiritual and psychical health, and implies a close connection between the landscape, environment, and ecosystems and the social and spiritual healthy development and identity, belonging. Birgejupmi for a person or community means ways to manage and to have good life socially, economically, spiritually and in respect to health.

Reciprocity and dialogue The traditional Sámi outlook on life is based on notions that reflect the relationship between humans, animals, non-human beings, nature, gods and other powers. In this relationship humans and nature are not opposed to each other. Rather, humans are an integral part of nature. On the other hand, nature – both physically and spiritually – is a part of the nature of humans and a source of strength for humans. The weakening of this reciprocal relationship and disruption of this balance may decrease the strength of humans. On an individual and collective level, the relationship to the internal and external world is maintained through rituals. These rituals keep the order of life in balance, which is very important for the survival of the community. Balance has been traditionally maintained by the Sámi people through rituals, by following normative patterns of behaviour, and established practices, by showing respect, and through a dialogue on both an individual and collective level. By following rules and normative patterns of behaviour people function, Sámi think and feel that they can achieve something. Especially in the worldview of the northern people, the well-being of both humans and nature depends on the balance between them. In Sámi spirituality and tradition both humans and nature are living and active interdependent beings. That is why a constant dialogue between these parts is necessary. Nature and everything that is part of it can be spoken to directly or indirectly. For example, in the 39

Kola Sámi oral tradition it is natural to say ‘You, my grandmother River’, ‘Thank you, old woman Lake’ etc. The relationship between humans and everything in creation is not only personal, but also has a moral meaning – the world around us is ethical and just.

Natural phenomena and spirits of nature In Sámi cosmology, many natural phenomena were considered universal, independent of people. These included, for example, the Midnight Sun, the Northern lights (aurora borealis), and the thunder rumbling during short summer. In Sámi cosmography, each of these had a role in explaining the origin and structure of the universe and the concept of time. It is worth mentioning that the traditional Sámi concept of time is not linear, but circular. For example, according to oral tradition, cosmic hunting of a wild reindeer or elk has happened since the beginning of the world and will never end. The hunters – in some stories the thunder god, in others the Sámi forefathers who invented skis and became stars (Gállá bártnit ‘sons of Gállá’ in North Sámi, three stars in the star constellation known as the Orion Belt) – can never reach the animal. That is why the thunder god is shooting his arrows (lightning, tiirmes tool ‘fire of thunder god’ in Kildin Sámi) from year to year. The constellation of Gállá bártnit never comes closer to the constellation of the Elk on the northern sky, but the hunters arise to the sky each evening trying to 40

reach the Elk, which is constantly moving away from them. These movements and happenings are a part of the cycle of the universe. Sámi people are aware of natural spirits and the realms that they control (see for example Bäckman, 1975; Porsanger, 1997a). In the names of natural spirits we find a reflection of the Sámi philosophy: one of the North Sámi terms for spirit vuoig ŋa is connected to the verb vuoi ŋŋat ’breathe’, as it is in many other cultures and languages. In the eastern Sámi languages names of natural spirits are compounds in which the world for ‘natural spirit’ can be translated as living being, creature, dweller, and inhabitant. The first part of the compound comes from the place where the spirit lives: for example, ‘water creature’ or ‘mountain dweller’. Natural spirits are not considered to be supernatural, physically invisible spirits or masters; they are creatures that live in the surrounding area; they are a part of living nature. Nature follows its own laws, and people need to know its way of life. The natural spirits must be taken into consideration when one settles on a new place, starts to fish, goes to hunt, or lives on a lake or a river. People need to follow certain rules to maintain the balance of nature in their nearest environment. The natural spirits control the way humans use nature.

Offerings The relationship with nature and its forces is not submissive but active.

Humans can, when necessary, influence the powers of nature by giving, offering, sharing, asking, promising, taking care of, showing respect to, or assuming the shapes of animals.

fishing and hunting, to protect reindeer herds, to bring good weather, to ensure good health, to ask a certain natural power to help people achieve what the people want.

Offerings were made to the natural spirits only when necessary: for example, when a spirit was known to be angry because people had broken some rule. One did not ask spirits for help, but for goodwill and patience while one stayed in their area. Every geographical place was considered an entity in which the physical dimension was in balance with the spiritual one. Both aspects needed to be taken into consideration when making a living. Therefore, the ideas about natural spirits are closely linked to the Sámi way of life.

The significance of sacred places is not found in the spirit or god controlling the place or the livelihood, nor in the offering or worship itself, but in the power of the thing worshipped. People live through the powers or nature, but they also live within these natural powers, as they do not separate themselves from nature and its powers. The aim of offering is to maintain the internal reciprocal relationship between nature and the people by seeking mutual benefit. When asking for goodwill or help of the natural powers, one must remember to strengthen the power through offerings and tokens of respect. Thus, the power of human beings and the power of nature are seen as interdependent.

Human beings know that natural powers influence their success in hunting and fishing, and they must therefore ask these powers to be kind and helpful. That is why individuals, families and communities found places to worship these powers. The term bassebáiki ’sacred place’ in North Sámi is often used in literature and means a place reserved for worship or considered sacred. These places are meant for the establishment and maintenance of a connection between humans, the natural environment and the powers of nature. The term bálvvošbáiki can be translated as ‘a place for offering’. The term sieidi (North Sámi, but known in all Sámi languages) designates the object of worship, especially a rock. In sacred places, offerings were made to enhance

Experts The establishment of a contact with the powers of nature can require special expertise. For this purpose there are experts who can act on behalf of a person, a family or a whole community. Instead of the term of shamanism, which has been used in the study of religions, the Sámi term of noaidevuohta was introduced in the 1990s to the study of indigenous Sámi religion by Professor Håkan Rydving (1993, 1995). Noaidevuohta (‘shamanism’) is not considered a form of religion or a practical aspect of a special naturalis41

tic religion today; it is thought to be linked with the way of life and culture of a people. The Sámi noaidevuohta is based on the worldview of a people who are dependent upon nature, and it is in harmony with the environment, and the economic and social structures. The Sámi noaidevuohta is not just a collection of rites and practices and folklore that explains these structures, but a way of perceiving the world around oneself and acting in it. The term of shaman is not suitable for the Sámi tradition, since there are own indigenous terms for spiritual experts and leaders. In North Sámi, noaidi is a term for spiritual experts, men and women, who are better than others at contacting the powers of nature and the world beyond. There are also different kinds of spiritual ‘experts’, ‘those who can see’, ‘those who know’, medicine men etc., and there is a variety of terms for different spiritual experts. The Sámi noaidi was the most important member of the community. Noaidis were the ones who maintained the world order among the people – in the life of the community and individuals. They were in contact with the world beyond through their ecstatic experiences. In the Sámi tradition, as in the shamanistic tradition of many other northern peoples, the noaidi acted on behalf of the community in order to guarantee good luck in hunting and fishing, to protect the community’s lands and waters, and to enhance the well-being of the community. They foretold the future, made contact with the world be-

42

yond, inquired about secret things, and were healers. The strength of the Sámi noaidi traditionally lay in the fact that they had to master the laws of natural powers. They had to understand how the surrounding forces and the internal power of people influence each other, so that they could use these forces for the good of their community, while at the same time insuring that powers of nature were not depleted.

Holistic understanding The definition of religion can be connected to a clarification of how individuals and societies define their place in respect to the power or powers which decide the fate and destinies of people (Rydving (1993, 1995). For more scholarly discussions about definitions of religion, see Platvoet and Molendijk (1999), Braun and McCutcheon (2000). In the indigenous Sámi religion, a close and reciprocal relationship to the powers of nature plays a central role. Everything in the world has been seen as interrelated. The main idea of the Sámi philosophy and worldview comes clearly from the Sámi religious tradition connected to offerings, sacrificial places, sacred mountains, waters, natural phenomena and spirits, world of animals, spiritual experts and their activities. The surrounding forces of nature and the internal power of individuals and communities influence each other. Individuals and communities need to maintain bal-

ance in order to make their living and to ensure their well-being. This presupposes that people think about the world and themselves in a holistic and reciprocal way. This understanding is found in the present-day language use. The above mentioned concept of birgejupmi, ‘maintenance of life’, describes a holistic Sámi understanding of well-being and survival and interdependence of everything in the world.

For a more complete explanation of the indigenous Sámi religion the author suggests the following articles: Kulonen et al. (2005), Rydving (2003, 2004, and 2010), Pentikäinen (1997 and 2002) and Porsanger (1997b, 1999, 2000a, and 2000b).

43

References Bäckman, L. (1975), Sájva: Föreställningar om hjälp- och skyddsväsen i heliga fjäll bland samerna [Sájva: Helping spirits of the sacred mountains among the Sámi]. (Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion 13). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. Braun, W. and McCutcheon, R. T. (eds.) (2000), Guide to the Study of Religion. London & New York: Cassell. Grim, John A. (1998, 2004), Indigenous Traditions and Ecology: Introduction to Indigenous Traditions (http://fore.research.yale.edu/religion/indigenous). The original publication: Earth Ethics 1998 (Fall): 10, 1. Harvey, G. (ed.) (2000), Indigenous Religions: A Companion. London: Cassell. Harvey, G. (ed.) (2000), Readings in Indigenous Religions. London: Continuum. Kulonen, U.-M., Seurujärvi-Kari, I. and Pulkkinen, R. (eds.) (2005), The Saami – A Cultural Encyclopaedia. (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia 925). Helsinki: SKS. Long, C.H. (2004), A postcolonial meaning of religion: Some reflections from the indigenous world. In Beyond Primitivism: Indigenous Religious Traditions and Modernity, pp. 89–98. Olupona, J. K. (ed.) (2004), Beyond Primitivism: Indigenous Religious Traditions and Modernity. New York: Routledge. Pentikäinen, J. (1997), Die Mythologie der Saamen. [Übersetzung aus dem Finnischen Angela Bartens]. (Ethnologische Beiträge zur Circumpolarforschung Bd. 3). Berlin: Reinhold Schletzer Verlag. (1998). Shamanism and culture. Helsinki: Etnika Co (ed) (2002). Fragments of Lappish mythology / Lars Levi Læstadius. Translated by Börje Vähämäki. Beaverton, Ont.: Aspasia Books. Platvoet, Jan and Molendijk, Arie L. (eds.) (1999), The Pragmatics of Defining Religion. Contexts, Concepts and Contests (Studies in the History of Religions 84). Leiden: Brill. Porsanger [Sergejeva until 2002], J. (1997a), Ihminen ja luonto koltta- ja kuolansaamelaisten maailmankuvassa [Man and Nature in the worldview of the Kola and Skolt Sámi]. Lisensiaatin työ. Helsingin yliopisto, uskontotieteen laitos. (1997b), Noaidiene blant samene på Kola. – Ottar 1997: 217, 28–36. Tromsø. [The Sámi noaidis (shamans)] (1999), Traditionell samisk tidsregning: årstider og navn på måneder/ Áigeipmárdus sámi árbevierus: jahkeáiggit ja mánnonamat [Traditional Sámi understanding

44

of time: the seasons and the names of months]. – Almanakk for Norge 2000: jubileumsutgave. Universitetet i Oslo. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, pp. 167–177. (2000a), Noen samiske stjernebilder: et jaktfolks forestillinger om stjernehimmelen [Traditional explanations of some Sámi star constellations]. – Almanakk for Norge 2001. Universitetet i Oslo. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag. (2000b), The Sun as Father of the Universe in the Kola and Skolt Sami Tradition. Pp. 233–253 in Pentikäinen, J. & H. Gaski & V. Hirvonen & J. Sergejeva (eds.) Sami Folkloristics. (NNF Publications 6, Nordic Network of Folklore). Åbo. (2007), Bassejoga èáhci: Gáldut nuortasámiid eamioskkoldaga birra álgoálbmotmetodologiijaid olis // The Water of the Sacred River: The Sources of the Indigenous Religion of the Eastern Sami Examined Within the Framework of Indigenous Methodologies. Kárášjohka: Davvi Girji. Rydving, H. (1993) (1995), The End of Drum-Time: Religions Change among the Lule Saami, 1670s – 1740s (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Historia Religionum 12). Uppsala: Uppsala universitet. (2003), Traditionell nordsamisk religion omkring år 1700 [Traditional North Sámi religion around the year 1700]. In Mytisk landskap: ved dansende skog og susende fjell. Ed. By Arvid Sveen and Håkan Rydving, pp. 9–23. Stamsund: Orkana. (2004), Saami responses to Christianity: Resistance and change. In Beyond Primitivism: Indigenous Religious Traditions and Modernity, pp. 99–107. (2010), Tracing Sami traditions: In search of the indigenous religion among the Western Sami during the 17th and 18th centuries (Instituttet for sammenlignende kulturforskning / Serie B Skrifter vol. 135). Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture Novus forl. Schanche, A. (2002), Meahcci – den samiske utmarka [Meahcci – the Sámi outfield]. – Svanhild Andersen (ed.), Samiske landskap og Agenda 21 (Dieđut 1/2002). Guovdageaidnu: Sámi Instituhtta.

45

46

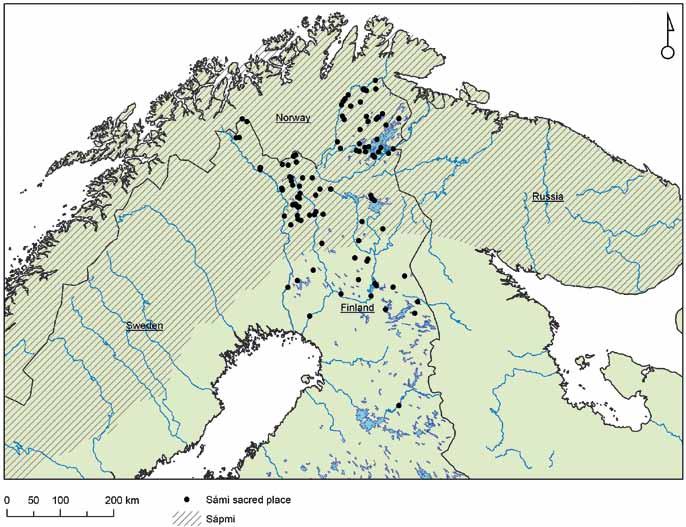

Archaeology of sieidi stones. Excavating sacred places Tiina Äikäs