“The difference between a childhood and a boyhood must be this: our childhood is what we alone have had; our boyhood is what any boy in our environment would have had.”

(Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 165)

“One thing is true is that the impressions you get in your first 18 or 20 years are probably the most intense you get. . . .”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 168)

“In my childhood and youth, radio was everywhere—in the barber shop, at the dentist’s, and on its own little table in the parlor off the living room—a dome-topped brown Philco with an orange dial.”

(Updike, John. More Matter. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. 803)

“Various artists and writers have influenced me at different times. My first really artistic hero was Walt Disney. I wanted to work for him. Then I sort of fell in love with The New Yorker. It began coming into the house when I was about 12.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

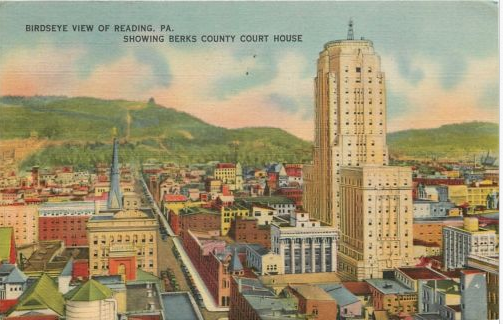

“Pennsylvania, where I spent my first 18 years, is a place of vivid impressions, even after more than 30 years away. When I sit down to write about the area of my youth, somehow I’m excited by returning—if only in my mind—to those rather pedestrian streets. I grew  up in the Reading area. It was a grand place—thriving downtown, factories pouring out smoke and textiles and steel and pretzels and beer. It was a town that made things. It was a muscular, semi-tough kind of place. . . . I was brought up in two houses within one county. And so I’ve had a more stable early life than most young Americans now, when there’s a lot more moving around and a kind of placelessness that you feel in fiction written by young people.”

up in the Reading area. It was a grand place—thriving downtown, factories pouring out smoke and textiles and steel and pretzels and beer. It was a town that made things. It was a muscular, semi-tough kind of place. . . . I was brought up in two houses within one county. And so I’ve had a more stable early life than most young Americans now, when there’s a lot more moving around and a kind of placelessness that you feel in fiction written by young people.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 183)

“I feel that there’s something particularly fruitful here for becoming a writer. I find there is a sense of human richness here. Puritanism didn’t touch the area with a heavy hand. You have more access to people’s real selves and not their social masks—there’s a richness and a brutality.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

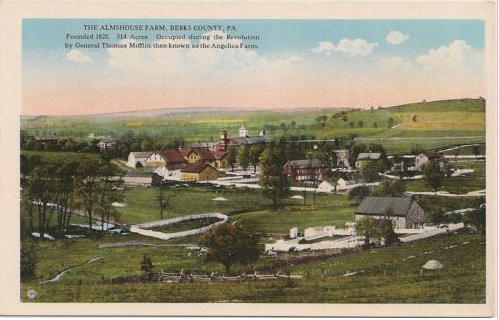

“[Shillington] was a town, a square-mile town that looked like a lot of other towns in Pennsylvania, a lot of row houses . . . . Our neighbors remained the same and my father was very lucky to get a job teaching high school, because he really was out of work and quite scared. He was frightened to not have a job, and to have a wife and a new child and responsibilities and no net under him, as they say. There was, however, a poorhouse at the end of my street and my father always said he liked being there, because if worse came to worst he could always walk to the poorhouse.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

“I am an only child and we were not rich but we were not exactly on skid row, either. My father was a high-school teacher, which didn’t bring in much money but was respectable. We had some status in the town. It was a town of 5,000, so a high-school teacher’s son was somebody. Many people knew me by name. We lived with my grandparents, my mother’s parents, in their house. My grandfather was in his way a distinguished man, too. He was a lovely talker. He really had that old-fashioned way of talking as a kind of performance. He had been in his 40s when my mother was born, so he was 90 when he died and I was 23. That makes him almost 70 years older than I. So I had the benefit of living with a man of the past.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 166-67)

“A little gravel alley, too small to be marked with a street sign but known in the neighborhood as Shilling Alley, wound hazardously around our property and on down, past an untidy sequence of back buildings (chicken houses, barns out of plumb, a gunshot, a small lumber mill, a shack where a blind man lived, and the enchanted grotto of a garage whose cement floors had been waxed to the lustre of ebony by oil drippings and in whose greasy-black depths a silver drinking fountain spurted the coldest water in the world. . . . on down to Lancaster Avenue, the main street where the trolley cars ran.”

Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 153)

“We have a large grape arbor, and a stone birdbath, and a brick walk, and a privet hedge the height of a child and many bushes behind which my playmates hide. There is a pansy bed that in winter we cover with straw. . . in our garden grows, among other vegetables, a bland, turniplike cabbage called kohlrabi, which I have never seen, or eaten, since the days when, for a snack, I would tear one from its down with my hands.”

(Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 152)

“There was a front porch, a side porch, and an upstairs porch, and the yard had held cherry trees, a walnut tree, a birdbath, a bed of lilies of the valley, and a vegetable garden that his grandfather turned with a shovel every spring.”

(Upike, John. “The Black Room.” The Afterlife and Other Stories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994. 563)

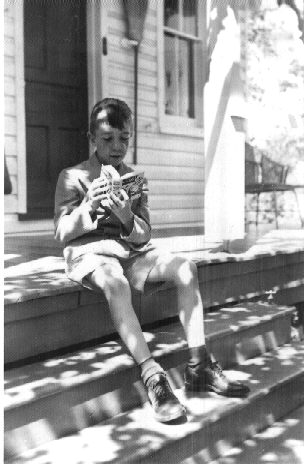

“It was one of my favorite places in the world: the side porch of the house at 117 Philadelphia Avenue . . . . On this long side porch . . . I would play by myself or with others—setting up grocery stores out of orange crates and crayoned paper fruit, making cozy houses out of overturned wicker porch furniture.”

“It was one of my favorite places in the world: the side porch of the house at 117 Philadelphia Avenue . . . . On this long side porch . . . I would play by myself or with others—setting up grocery stores out of orange crates and crayoned paper fruit, making cozy houses out of overturned wicker porch furniture.”

(Updike, John. More Matter. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. 671-72)

“And then there was a squirrel, Tilly, that we fed peanuts to; she became very tame, and under the grape arbor would take them from our hands.”

(Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 154)

“I was kind of a happy, cheerful child—liked school, liked my playmates. Mostly girls, actually, on that particular block, for some reason. A lot of girls, who didn’t venture very far, so I kind of took the children who came in from the eight houses around, and they were girls and kind of gentle and didn’t bully me or anything, weren’t mean to me. There was a nice playground within a walk. I could walk to everything. I got a tricycle and then a bicycle.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

“I did draw a lot as a kid. In fact, my first hope was to be a cartoonist or an artist of some sort, and it died slowly. Going to Harvard was, I suppose, the crucial mistake, because it turned out not to be a very good school for training practical artists, but it is pretty good for writers. So I emerged more of a writer than an artist—although I did draw until about the age of 22-23.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 217)

“It’s very hard for me to reconstruct these days because this great leap up out of Shillington now seems kind of surreal. . . . began by writing a lot of light verse, light verse for the high school literary magazine. It was a weekly called The Chatterbox. . . . I tried a few short stories but I really didn’t have a clue about fiction. . . . When I was a sophomore I thought I’d write a novel. It was called Willow and it was about what you might expect, a small town rather like Shillington, where I’d been raised.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 164)

“I have a growing sense of wonder about this little stretch of sidewalks that have received so many of my footprints.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

“When I first began to write, Reading and Shillington and Berks County were simply life to me. It was all I knew. I had hardly left the county until I was eighteen, so that my first stories and novels were very unselfconsciously about this area. Berks County is one of the main centers of what they call ‘Dutch Country,’ meaning ‘Deutsch Country,’ so there’s a kind of flavor here. Along with a lot of other imported Americanisms, there’s a German base. I think that people have that German conscientiousness. They try to keep their places clean and, generally, if they’re given a job, they do it. Even I, I’m told, am a rather hard-working author. I think it’s a county of hard-working people.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 221-22)

“I was happy in Shillington. I wasn’t especially popular or athletic or anything, but I was smart—’schmart’ as they used to say. And so I was—it was fine in Shillington.”

(Baver, Kristin. “John Updike: Berks County Runs through His Novels. Berks County Living, February 2008: 30)

“[The people of Shillington] sheltered me for the first 13 years of my life, and it was a nice time to grow up in. And they shared—there’s a sharingness you realize, looking back. People in that part of Pennsylvania are somehow more open. And there’s a sort of warmth that got me through the Rabbit novels. That Pennsylvania—Lutheran or something, I don’t know what it can be traced to—but there’s something about it that makes it easy to write about.”

(Hoerr, Dorothy. “In the Limelight: Shillington Native, World-Renown Author John Updike.” Berks County Living, November 2004: 48)

“Yes, that whole world [of writers] seemed magical. There was, however, my mother, who was trying to to be a writer, so that the basic tools of writing—that is, the typewriter, the paper, and the manila envelopes—were all in the house, and I used to watch her type and I used to watch her send the things off and hope for the best. Eventually she did get

published, although perhaps never as much as her gifts deserve. . . . My father taught junior high math, and I was his student for not one but three years—all those junior high  years. Indeed, he was my homeroom teacher for one of those years. . . . But, yes, it is a strange thing to see your father at work, as it were, and what I got out of it was two things really: A sense of pride, seeing him perform—because I saw him in high-school assemblies, and he was the funniest of the teachers and would say things which would make the whole auditorium roar with laughter. And I thought, crouching down in my seat, that that’s my dad and was kind of amazed. On the other hand, I did see, especially as he got older, the real struggle that teaching is—keeping discipline and saying the same things for the 15th year in a row—and so a sense of his agony, that is, the agony of the working teacher, was born in me also.”

years. Indeed, he was my homeroom teacher for one of those years. . . . But, yes, it is a strange thing to see your father at work, as it were, and what I got out of it was two things really: A sense of pride, seeing him perform—because I saw him in high-school assemblies, and he was the funniest of the teachers and would say things which would make the whole auditorium roar with laughter. And I thought, crouching down in my seat, that that’s my dad and was kind of amazed. On the other hand, I did see, especially as he got older, the real struggle that teaching is—keeping discipline and saying the same things for the 15th year in a row—and so a sense of his agony, that is, the agony of the working teacher, was born in me also.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 213-14)—Insert is Updike’s yearbook entry for senior year)

“I remember as quite a small child watching my mother try to write, in Shillington, and it was the same room I was put in when I was sick in bed [the front ‘guest’ room]. When I was sick I would watch her trying to write and I even remember she would ask me to stop talking. I’ve never heard a harsh word from her before, really, and this insistence on silence was one of my first lessons on how to be a writer. . . .”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

Shillington was “the kind of town where the town cop would dress up as Santa Claus on Christmas afternoon and give you a box of candy in the Town Hall. There was this sort of institutional coziness that was delightful to a child. I think that Berks County probably was an exceptionally pious and family-centered sort of place. So I’ve carried out into a world where both piety and the family are taking a beating, I carried out a certain . . . whatever strength such an upbringing gives you, and also a sense of possible ideal behavior, of human organization that I hold the people in my novels up against.”

(Updike, John. Remarks made at a 1983 press conference, upon receiving the Distinguished Pennsylvania Artist Award)

“All through those years Pappy Shilling, the surviving son of the landowner after whom the town was named, walked up and down Philadelphia Avenue with his thin black cane and his snow-white bangs; a vibrating chain of perfect-Sunday-school-attendance pins dangled from his lapel. Each autumn the horse-chestnut trees dropped their useless, treasurable nuts; each spring the dogwood tree put forth a slightly larger spread of blossoms. . . .”

(Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 154)

“I seem to keep coming back to writing about Pennsylvania. I sing the odd corner of Pennsylvania where the people are average, not stupid.”

(Miller, Karen L. “Updike Reflects on ‘Shillington Thoughts.'” Reading Eagle, December 10, 1989: E-1)

“The neighborhood—the feeling and the kind of houses—is certainly in all my fiction. I do get very excited here. I find I begin to talk very rapidly and jump around a lot, just being in the blocks, the streets.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 222)

“Corn grew in the strip of land between the alley and the school grounds. We ourselves had a large vegetable garden, which we tended not as a hobby but in earnest, to get food to eat. We sold asparagus and eggs to our neighbors. Our peddling things humiliated me, but then I was a new generation. . . . We kept the food money in a little recipe box on top of the icebox.”

(Updike, John. Assorted Prose. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. 165-66)

“The image of a high school meant extra much to me, because my father taught at one and I, of course, finally went to one, so that not only Rabbit, Run, but many of my short stories are about high schools as shapers of American character.”

(Updike, John. John Updike’s Pennsylvania Interviews, ed. James Plath. Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh Univ. Press, 2016.)

“Harry [‘Rabbit’ Angstrom] stayed in Pennsylvania instead of leaving, and maybe it’s one of my ways of staying there while also leaving.”

(Cheshire, David. “John Updike: A Small-Town Boy Who Tried to Make the Most of What He Had.” The Listener, January 28, 1982: 4-6)

“I do sometimes accept a speaking invitation in Pennsylvania, so I do try to come back once a year—because it’s my native turf, and I didn’t just have a casual Pennsylvania upbringing. I think really in my first 18 years of life, there were hardly 20 days that I didn’t spend in Pennsylvania.” (Hoerr, Dorothy. “A Conversation with John Updike.” Berks County Living, November 2004)

“We took a few trips to the Jersey shore, but we were too poor most of the time to take vacations. I used to go to Shillington playground. I thought that was very exciting. I played a lot of basketball there.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 243.)

“There was indeed a poorhouse a couple of blocks from where I grew up, but I very rarely went into it, and there was a fair that must have impressed me as a child. . . . They were tearing the poorhouse down at Shillington and I went up and looked at the shell. My grandfather [John Hoyer], who is somewhat like John Hook in that book, was recently dead, and so the idea of some kind of memorial gesture, embodying what seems to have been on my part a very strong sense of national decay, crystallized in this novel.”

“There was indeed a poorhouse a couple of blocks from where I grew up, but I very rarely went into it, and there was a fair that must have impressed me as a child. . . . They were tearing the poorhouse down at Shillington and I went up and looked at the shell. My grandfather [John Hoyer], who is somewhat like John Hook in that book, was recently dead, and so the idea of some kind of memorial gesture, embodying what seems to have been on my part a very strong sense of national decay, crystallized in this novel.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 47)

“[With the Rabbit books] I’ve in a way extended my youth a bit. A lot of the Rabbit books is what I imagine Pennsylvania to be like from an adult point of view. But the impressions you get in your first 18 years, you do feel very sure about them, so that in a sense I know how things happen in Pennsylvania.”

(Updike, John. Conversations with John Updike, ed. James Plath. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1994. 170)