Note: This post is longer than usual. I had considered running it in two installments but thought it would lessen the impact of its message by doing that.

So sit back with a cup of coffee, relax and read. 🙂

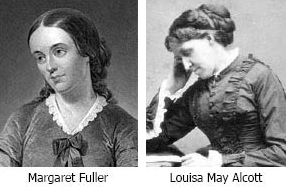

Two ladies,

Two ladies,

same vision

Two New England feminists, both heavily influenced by transcendentalism.

Both in the company of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Bronson Alcott.

Both very reform-minded.

Both would forever change history for women.

Louisa May Alcott and Margaret Fuller were neither friends nor colleagues yet they shared a similar passion for women’s rights, believing it was best for society.

Continuing with the theme of yesterday’s post, Pulitzer prize-winning author John Matteson drew connections between these two women while highlighting their different approaches.

What was Margaret Fuller’s vision for women?

Margaret Fuller, much like Bronson, believed in attaining spiritual perfection. She was the most passionate of the transcendentalists, that passion often spilling over to the individuals themselves.

Much more than a flirt …

It is titillating to read about her intense relationships with Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne (not a transcendentalist, but he did base the heroine of The Scarlett Letter on Margaret – see Wikipedia on Margaret Fuller) but it is also distracting. Margaret may have been a flirt but she was brilliant.

Living her words

A woman’s voice was needed in the Transcendentalist movement and she brought it. While Bronson and Emerson talked a great game regarding the value and worth of women, Margaret lived it, educating women through her writing and her brand of “conversations.”

The vision laid out

Women in the Nineteen Century is Margaret’s tour de force, where she lays out her vision for women.

Matteson laid out Margaret’s demand for full rights for women, well beyond the political and economic; this would include equality spiritually and intellectually.

Bringing virtue to the marketplace

A reformer at heart, she believed that women needed to be in marketplace in order to bring about reform. Taking the traditional role of the wife leading the husband to greater virtue, she extends it out to the greater society: women in business would lead the marketplace (and the men in it) to greater virtue.

A reformer at heart, she believed that women needed to be in marketplace in order to bring about reform. Taking the traditional role of the wife leading the husband to greater virtue, she extends it out to the greater society: women in business would lead the marketplace (and the men in it) to greater virtue.

Man versus Men, Woman versus Women

Margaret was a philosopher greatly influenced by Transcendentalism. She, like Bronson Alcott, believed in attaining spiritual perfection. Part of that perfection involved gender. Daily reality had placed men and women in narrow roles and neither gender was free because of what she called, “debased living.”

Note that the original title of Women in the Nineteenth Century had been “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men, Woman versus Women”; it was originally a series of essays serialized in The Dial, the Transcendentalist magazine that Margaret edited for Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Note that the original title of Women in the Nineteenth Century had been “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men, Woman versus Women”; it was originally a series of essays serialized in The Dial, the Transcendentalist magazine that Margaret edited for Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Effects on marriage

The distortion of the genders in turn, warped the institution of marriage Margaret believed that the dependency of women on men had debased marriage and sex. She remained single for several years until she had a child with Italian revolutionary Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, a marquis who had been disinherited by his family. While it is assumed they were married but there is no hard evidence that they did (source: Wikipedia).

Lead by deeds

Placing reform above all else, Margaret felt that women did not necessarily need to rule but to lead by example. In order to do that, it was imperative not to impede the soul. Each man and woman had to be free to realize their full potential, be who they were meant to be.

Benefits to society

This freedom, however, was not meant just to satisfy individual wants. Here Margaret led by example. She denounced not only the treatment of women but African and Native Americans as well. She advocated for reform in prisons, visiting women in Sing Sing in October of 1844 and even staying overnight (source: Wikipedia). She raised concerns for the homeless, especially in New York (Ibid).

On the same page

If you are familiar with Louisa’s beliefs on women and reform, you can see in similarities already between the two women from Matteson’s description of Margaret’s vision.

Louisa’s vision for women and society

Spiritual father …

Louisa came from one of the founders of Transcendentalism, Bronson Alcott. He was all about spirituality, perfection and becoming divine.

… and reformer mother

But she also came from her mother Abba, a pragmatic reformer. Unlike her philosophical husband whose head was in the clouds, Abba practiced her Christianity day to day, often giving to others out of her family’s own want (Bronson practiced this also, believing that God would always provide).

Bronson exuded serenity as he sought to perfect himself. Abba passionately wrestled with life and others to bring forth reform. Her most noteworthy efforts were in Boston in the 1840s as one of the first social workers.

Bronson exuded serenity as he sought to perfect himself. Abba passionately wrestled with life and others to bring forth reform. Her most noteworthy efforts were in Boston in the 1840s as one of the first social workers.

Societal change needed

Coming from such a background, it is no wonder that Louisa felt that society must be reordered. It began with freeing the slaves.

Belief coming from experience

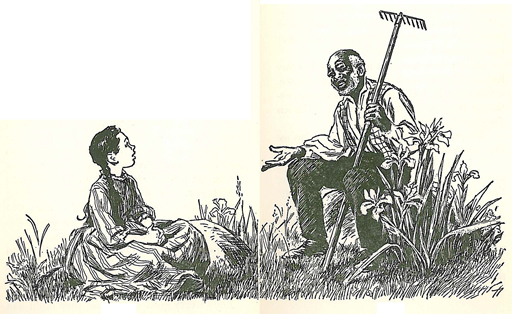

Matteson noted an incident when Louisa was 3 which most likely opened her eyes to African Americans as equals. While living in Boston, she fell into the Frog Pond; she was rescued by a black boy. She notes in her writings that this boy lit the flame of abolition in her heart.

Living out that belief

Throughout her life, Louisa helped her parents shield and transport runaway slaves to Canada; their home in Concord, known then as Hillside, was on the underground railroad.

With pride, Louisa notes that she served tea to John Brown’s widow at Orchard House.

An rare open statement

Louisa didn’t usually state her feminist views blatantly in her fiction writing. One exception was Hospital Sketches where she writes, “I’m a woman’s rights woman, and if any man had offered help in the morning, I should have condescendingly refused it, sure that I could do everything as well, if not better, myself.” (from Chapter 1, Hospital Sketches)

Another was a short story, “Happy Women.” This excerpt explains in a nutshell Louisa’s vision for womanly happiness:

This class is composed of superior women who, from various causes, remain single, and devote themselves to some earnest work; espousing philanthropy, art, literature, music, medicine, or whatever task taste, necessity, or chance suggests, and remaining as faithful to and as happy in their choice as married women with husbands and homes.

Subterfuge in her writing

Most of the time she teased out her views in her writing. She would describe the lives of purposeful women who earned their keep and remained independent. Matteson described the importance of work to Louisa saying that life was full of work that needs to be done, and it needs to be done by both sexes.

Becoming the best she can be

Becoming the best she can be

Louisa believed as did Margaret that women needed to develop themselves for if a woman developed her talent fully and used it for others, she would be happy. And just as Margaret led by example, so did Louisa, becoming a best-selling author.

Using her bully pulpit

In that position, Louisa could wield a lot of influence and she took every advantage to use it. While Jo March is often cited as the best example of an independent woman, Matteson used the example of Polly from An Old-Fashioned Girl who takes her well-off, bored and disgruntled friend Fanny to visit her sisterhood of working, purpose-filled women. Fanny’s life is changed forever after seeing that life could be so much more than the emptiness of parties and fashion.

Giving your best

Louisa was also greatly valued sacrifice. Like Margaret, a woman’s right to reach her potential was not just for herself; she was to give her best to those around her. This belief plays out again and again in her books.

Duty’s faithful child

Bronson distrusted Louisa’s selfless intentions until she became a nurse. When he saw how she was willing to give up her own life for others by nursing, he wrote his famous sonnet to her, “Duty’s Faithful Child.”

Using her right to vote

Matteson ended his lively presentation with an ironic anecdote. Noting that Louisa was the first woman to register and then to vote in Concord, he quipped that the registrar gave her a literacy test! She also was required to sign her name to prove she could write.

It was the one time in her life that she was in a hurry to pay her taxes so she could qualify. 🙂

Click to Tweet & Share: Two ladies who would change the lives of women forever: Louisa May Alcott and Margaret Fuller http://wp.me/p125Rp-16Q

Click to Tweet & Share: Two ladies who would change the lives of women forever: Louisa May Alcott and Margaret Fuller http://wp.me/p125Rp-16Q

![]() Are you passionate about Louisa May Alcott too?

Are you passionate about Louisa May Alcott too?

Send an email to louisamayalcottismypassion@gmail.com

to subscribe, and never miss a post!

Facebook Louisa May Alcott is My Passion

More About Louisa on Twitter

![]() Susan’s ebook, “Game Changer” is now available From the Garret – download for free!

Susan’s ebook, “Game Changer” is now available From the Garret – download for free!

Unlike Louisa May Alcott, Margaret Fuller did eventually marry an Italian Revolutionary. Unfortunately we know little how marriage may have changed her ideas.They perished together shortly after, along with their infant son, in a shipwreck 1850.

Ooo, my bad! I knew that but didn’t proofread carefully enough before posting. Thank for catching that! I’ve since corrected my post to reflect it.

Yay, Louisa. I’m not sure I remember correctly, but didn’t Abba also register to vote then? I wonder if she let LMA go ahead of her in line?

Abba would have loved to have been there with Louisa to register to vote, but she had unfortunately did not live long enough. She had died a few years before. I’m sure she was with Louisa in spirit. 🙂

Abba would have been thrilled to have shared that with Louisa. I imagine her mother was very near to her in spirit that day.

Excellent post–now I have to read up on Margaret Fuller. I like the factoid that Hawthorne based the character Hester Prynne on her.

BTW, thanks for visiting my blog–turns out that we did see people canoeing by the Old North Bridge and I thought it looked like such a marvelous way to spend the afternoon. Next time!

Thanks for stopping by! I did a post on my trip on the Concord, here’s the link: https://louisamayalcottismypassion.com/2011/08/18/tapping-into-my-inner-thoreau-play-acting-as-sylvia-yule/ I loved being able to first paddle under the bridge, then, park my boat and walk over it! 🙂

What an informative post! Can I clarify that Margaret Fuller and Louisa May Alcott were not friends…? I was under the impression Fuller taught Alcott or they interacted at some point at Theodore Parker’s church or Emerson’s house, I’m not sure where I got that from so wanted to check! Thanks Susan for all the research and thought you put into these posts!

Margaret Fuller was friends with Louisa May Alcott’s father, Bronson. Fuller was an assistant in Alcott’s Temple school. She also visited Concord frequently int he 1840s, when the Alcott’s lived there. Alcott recounts a humorous incident when Fuller asked to she the “model children” and the Alcott girls came careening around the corner in a wheelbarrow, which they promptly upset. So, Alcott certainly knew Fuller as one of her parents friends in her childhood, but the extent of her influence and their relationship is undocumented. Off the top of my head, I’m not certain the two women ever interacted at Parker’s Church. If I am remembering correctly, Louisa was mostly active in his congregation after 1850. Fuller went to NYC in 1845 and to Europe in 1846, when Louisa was thirteen and fourteen, receptively, and died in 1850 before returning to America. Hope this helps!

That’s really helpful, thank you for such a detailed reply! Fascinating, the connections that could have been but weren’t…

Kristi, thanks for this!

Thank you! Fuller was a lot older than Louisa though I feel had they been closer in age they might have been friends. I know she was inspired by her.

Yes! You’re welcome!