The Amy Lowell Letters Project (ALLP), an open-access, digital scholarly edition of the letters of American poet, editor, and critic Amy Lowell (1874–1925). I am the PI, Project Director, and editor. Complete list of ALLP team members, past and present, here.

about amy lowell

At the time of her death in 1925, Amy Lowell was one of the most celebrated, sought-after, and fought-about authors in America. Her books–both poetry and criticism–were best-sellers and her tempestuous lectures and readings drew crowds of thousands and fueled countless news reports. She published prodigiously during her fifteen-year career (1910-1925): six volumes of poetry (three more were published posthumously), two volumes of literary criticism, a two-volume biography of John Keats, and countless articles and reviews. What’s O’Clock, in press at the time of her death, won the 1926 Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

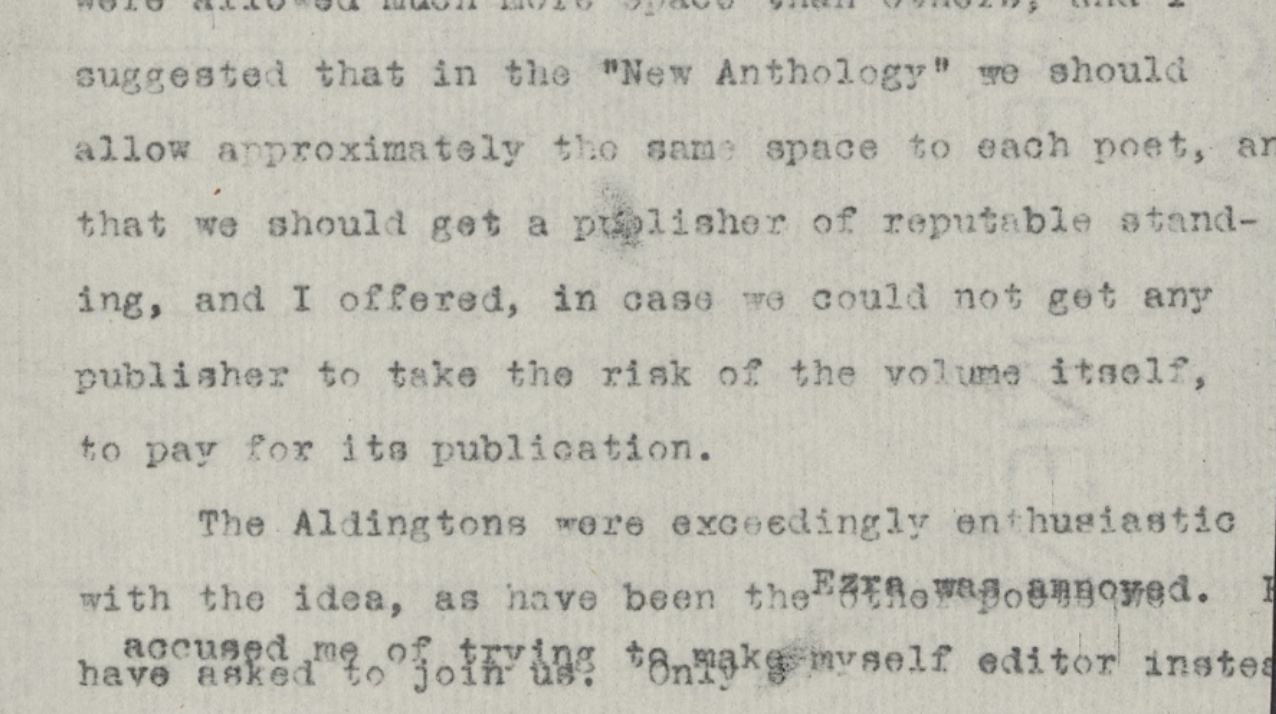

Early in her career fellow American poet Ezra Pound included her poem, “In a Garden” in his influential 1914 Des Imagistes anthology, but the two soon had a falling out over Lowell’s plans to aggressively market Imagism, the loosely-organized poetic style that initially brought them together, by publishing an annual Imagist anthology with a major commercial press.

Some Imagist Poets (1915, 1916, 1917), published by Houghton Mifflin, edited by Lowell, and featuring poems by H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and D.H. Lawrence, among others, introduced modernist poetic experimentation to a general readership, and turned Imagism into a full-blown poetic movement. Promoting the anthologies in lecture tours, Lowell schooled over-capacity crowds across America in how to read and appreciate Imagism, free verse, and experimental poetry more generally. For many Americans of her era, she was the face of modern poetry.

about amy lowell’s letters

Unfortunately, Lowell’s critical reputation suffered in the years following her death, primarily because her successes in marketing Imagism left her vulnerable to charges that she was less poet than propagandist. Only portions of the lively correspondence that documents her centrality to modern poetry have been published, and only in connection with other figures. No representative collection of her letters exists, even though—according to the librarians at Harvard University’s Houghton Library, where Lowell’s papers are housed—hers is one of the most accessed archives in the library, largely because she corresponded with virtually all the most prominent writers and publishers of her time.

Lowell’s letters are scholarly, newsy, and practical, full of candor, warmth, and scorn. They show the depth of her investment in the New Poetry movement, in the growth and success of the poets writing it, and in the little magazines publishing it. They reveal, as well, the many roles she played, as a poet, editor, critic, and de facto literary agent. She was involved in everything from designing book covers, to writing ad copy, advising marketing plans, and negotiating royalties. The letters show her in conversation with some of the best-known American and European poets of the early twentieth century, but they also show her engaged in equally impassioned conversations with once prominent literary figures less well known today.

Perhaps most importantly, her letters reveal the depth and complexity of her relationships with behind-the-scenes players whose roles in establishing what we now consider the modern poetry canon are usually underrepresented or overlooked: editors of both little magazines and popular weeklies, heads of publishing houses, newspaper columnists, translators, literature professors, and book sellers.

ALLP goals and methodology

I have identified thirty-five key correspondences (approximately 1400 letters) related to Lowell’s career in poetry for ALLP. In the first phase of the project my team and I are focusing in particular on letters related to the first decade of the New Poetry movement (1912-1922). A digitized, searchable archive of Lowell’s letters will be a resource for researchers working in early 20thcentury poetry, periodical studies, book history, rare book and manuscript collecting, women’s history, queer studies, Anglo-American adaptations of Asian forms and translations, and Romanticism.

Foundational digital projects in modernism, such as the Modernist Journals Project, allow users to engage with periodicals as early twentieth century readers would have encountered them. Lowell’s letters, importantly, reveal the labor behind the finished product. In this way ALLP is a feminist project. Lowell was involved with many overlapping poetic networks. Her letters testify to her investment in working collaboratively with other poets–that’s the crux of the feud with Pound, who dismissed the Imagist anthologies as a “democratic beer garden” approach to poetry. But thinking of Lowell as a mentor, a colleague, a friend goes against reductive generalizations of her as an egocentric interloper, a rich woman who bought her way into a movement. We have tried to be similarly collaborative, transparent, and feminist in our approach to this work.

In encoding, our priority has been to tag information that can be used to trace the networks that Lowell helped to build—alliances, feuds, literary movements, etc. For now, this takes precedence over documenting the materiality of the letters. While Lowell’s letters have relatively fewer additions, deletions, and modifications than other collections, we do not wish for the labor and process behind the letters to be erased, especially as this work was primarily done by unnamed secretaries. Digitized annotated letters will also include links to the facsimiles and encourage readers to consider their physical qualities and labor in Harvard’s HOLLIS archive.

support and funding

The Amy Lowell Letters Project is generously supported by grants and fellowships from The National Endowment for the Humanities, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Newberry Library, The Modernist Studies Association, the Office of Research Services, Loyola University Chicago, and the Center for Textual Studies and Digital Humanities, Loyola University Chicago.