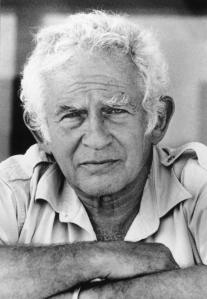

Norman Mailer’s writing was about dualities and disappointments. God and the Devil were engaged in an epic battle, and, no matter which side won, life was still excrement and death, “a bath in shit with no reward.” That last bit comes from his 1972 review of Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris, published in Mind of an Outlaw, a recent compendium of many of Mailer’s uncollected or out-of-print essays. The book culls together a lot of minor work, the Bertolucci review included, with a few of Mailer’s greatest hits mixed in. Still, Bad Mailer is better than a lot of other writing produced in the 65 years since he set in motion post-World War II fiction with the first line of The Naked and the Dead: “Nobody could sleep.”

As an example, Mailer most clearly outlined his philosophy, which remained consistent even as his styles and topics changed with each book, in an otherwise forgettable profile of Jimmy Carter from 1976, reprinted in Mind of an Outlaw: “Mailer,” he writes, referring to himself in his preferred third person, “had a notion of God as not clearly omnipotent but rather as a powerful God at war with other opposed visions of the universe.” As with God, so too Mailer. The first complete biography of Mailer, by J. Michael Lennon, the author’s longtime friend and archivist, suggests even with its title, A Double Life, that for all of Mailer’s concerns with the universe at large, more interesting was that good and evil were continuously waging war over his own soul.

Much of the first third of Mr. Lennon’s work relies on previously reported stories from former biographies of the author (and playwright, filmmaker, poet and occasional actor), especially Mailer: A Biography by Hilary Mills (1982) and Peter Manso’s comprehensive oral history, Mailer: His Life and Times (1985), both of which appeared not long after The Executioner’s Song solidified Mailer’s reputation as one of the great 20th-century writers. But Mr. Lennon is a fine apologist for Mailer’s less-appreciated work, including Barbary Shore, his critically despised follow-up to his beloved debut. It focuses on leftist radicals in Brooklyn, one of which is a World War II veteran trying to write a novel, Mailer’s first foray into blatant self-reference. Mr. Lennon makes the case that the novel’s publication around the beginning of the Korean War marred the book in “a period when anything that offered a socialistic alternative was abominated.” (Barbary Shore happens to be a favorite of Gore Vidal, Mailer’s recurring enemy; he wrote in The Nation that he admired the book for its “hallucinatory writing of a kind Mailer tried … only that one time.”)

Mr. Lennon, who had unprecedented access to the author and his papers, hits his stride in his meticulous recreation of the party Mailer threw for his friend Roger Donoghue beginning the night of Nov. 19, 1960. This was when Mailer announced to his friends his intention to run for mayor of New York City and then, a few hours later, stabbed his second wife, Adele. (“Double life,” indeed.) Even before the incident, Mailer’s reputation had tarnished after the critical failures of Barbary Shore, its successor, the criminally underrated The Deer Park and Mailer’s disastrous column in The Village Voice (Mailer, in his biography-by-way-of-career survey, Advertisements for Myself, called the public’s response “a blitzkrieg.” A sample: A column about Samuel Beckett’s new play Waiting for Godot begins, “I have not seen Waiting for Godot, nor read the text.”) He took a hiatus from fiction, and the sudden fame that had been heaped upon him after his first novel was receding, “a process as painful in America as the withdrawal of a drug from an addict,” as Gore Vidal wrote in his Nation piece.

Mr. Lennon calls Mailer stabbing his wife one of the author’s “memory crystals, an experience to be harvested,” so let’s go over the details, as reported by the biographer. The party was, in Mr. Lennon’s words, “the worst night of [Mailer’s] life,” though one must imagine it was worse for Adele. Mild-mannered Allen Ginsberg called Norman Podhoretz a “big dumb fuckhead.” A crasher “wrapped in bandages” tried to convince George Plimpton he had been a victim of police brutality. Meanwhile, a highly inebriated Mailer was stalking the room, staring people down and inviting them to go downstairs into the street to fight. Adele was also drunk and made a “fag crack” (Mailer’s words) at her husband. Tensions rose, and, early the next morning, Mailer stabbed Adele twice with a penknife, the one he used to clean his nails, once in the back and once in the chest, barely missing her heart. The next day, he formally announced in a taped interview with Mike Wallace that he would be running for mayor of New York on his own “Existentialist Ticket.” He then went to the hospital to be arrested. After a psychological evaluation, an investigator told Mailer, “Your recent history indicates that you cannot distinguish fiction from reality.” Mailer was booked in the psych ward at Bellevue but was ultimately found to be legally sane. His wife declined to testify against him, probably, according to Hilary Mills, though it goes unmentioned by Mr. Lennon, at the urging of her husband. He received three years’ probation. Adele’s story stops here, with Mailer’s famous friends blaming her for the incident and her children dismissing her as, to steal Mr. Lennon’s word, “bitter.”

LET ME TELL YOU about my Master’s thesis on Mailer. I wrote it in 2009, and it has rested ever since in the drawer that holds many semi-repressed memories that I can’t bring myself to part with. When I recently dug up the folder I keep it in, an index card with the following notes in my handwriting fell out:

– Myth of Mailer’s persona is fact.

– Writing is the truth.

– Mailer is an ass hole even when

he’s “not being” an ass hole.

I had a good laugh at that. The paper essentially pinpoints the moments in Mailer’s writing where autobiography seeps in and argues—as I recall, insufficiently—that Mailer believed journalism (which he and/or his publishers had a tendency to label as fiction), like all narrative writing, is several layers removed from reality—representational, even as certain details are presented as fact. I could not bring myself to reread the whole thing, but—before the pulpit of Mailer, always a sucker for self-flagellation—I offer an out-of-context line before moving on: “There is no Mailer. Or so it seems.” (“Too much?” my advisor commented in the margin.)

That Mailer was able to live the stabbing incident down is perhaps a testament to his talent. If anyone ever benefited from the biographical fallacy it was Mailer. It helped that he chose to fictionalize the event, exhuming its absurdities and bolstering them, allowing myth to overshadow history. By 1965, he reckoned with the worst night of his life (and, it should go without saying, a failed mayoral campaign) with his return to fiction, An American Dream, originally published serially in Esquire, in which a former politician and current television personality murders his wife (in chapter one, no less). Suddenly, the reality of Mailer’s explosion of violence was, like the original diagnosis of his troubled mind after stabbing Adele, indistinguishable from fiction. In this version, the wife dies, but that’s basically what happens in Mr. Lennon’s biography as well; apart from an aside here and there, she’s never heard from again, and Mailer is back to his old biblical ways: “I was gone like a bat and shaking hands with the Devil once more,” he writes in An American Dream.

Mailer, at this time, was turning into the greatest political commentator of his generation. His first attempt at political journalism was “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” a retrospective piece on the 1960 Democratic National Convention, which was held in Los Angeles. The article was on newsstands the same month that Mailer was starting to make his way through New York’s criminal justice system. The piece is the centerfold of the Mind of an Outlaw collection, overshadowing even Mailer’s most famous nonfiction essay included here, “The White Negro,” about the “muted cool religious revival” movement of hipsters and the counterculture as mere repercussions of the traumas of mass death by means of calculated genocide—be it a concentration camp or an atomic bomb with its “radioactive cities.”

If ”The White Negro” characterizes noncomformity as a return of America’s repressed doom after World War II had forever scarred its id, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket” is the country’s carnival-esque ego. Mailer was smart enough to treat the political convention as what it really is: not “housing projects of facts and statistics” but rather the marathon jack-off America treats itself to every four years, a spectacle of showmanship that speaks to what it is to be an American at a given moment in history.

Mailer breaks down the Kennedy cabinet, as well as the most minute features of his surroundings, in Dickensian detail. L.A. is “all open, promiscuous, borrowed, half bought, a city without iron, eschewing wood, a kingdom of stucco, the playground for mass men.” Kennedy is “a young professor whose manner was adequate for the classroom, but whose mind was off in some intricacy of the Ph.D. thesis he was writing.” The Democratic Party is “the Snopes family married to Henry James.” Nixon is seen only once, in a carefully placed parenthetical aside where he accepts his nomination, though he could just as easily be closing the gates of hell quietly behind him:

(“Yes,” Nixon said, naturally but terribly tired an hour after his nomination, the TV cameras and lights and microphones bringing out a sweat of fatigue on his face, the words coming very slowly from the tired brain, somber, modest, sober, slow, slow enough so that one could touch emphatically the cautions behind each word, “Yes, I want to say,” said Nixon, “that whatever abilities I have, I got from my mother.” A tired pause … dull moment of warning, “… and my father.” The connection now made, the rest comes easy, “… and my school and my church.” Such men are capable of anything.)

Most importantly, Mailer was becoming “Mailer,” his own greatest character. He uses the first person in “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” but, as if the reality of his own persona had become too great a burden, he would eventually merge his public persona—the one that ran for mayor a second time in 1969 and head-butted Vidal backstage at The Dick Cavett Show—with his writerly one, appearing in his stories as “Norman Mailer,” both present and omnipresent, a sustained metaphor for all his subjects on a hopeless quest for power and fame, more concept than man. I take the book that introduces the character, Armies of the Night, which is nominally about Norman Mailer, hungover from the night before, being arrested at the 1967 march on the Pentagon to protest the Vietnam War, to in fact be primarily about the creation of the “Norman Mailer” identity and its aftermath. This character allowed him to become blisteringly self-aware. He writes about himself in Armies of the Night: “He had in fact learned to live in the sarcophagus of his image. … Mailer worked for the image, and therefore he detested the portrait of himself which would be promulgated if no one could ever reach him.” Mailer, so reachable as a public intellectual engaging in shouting matches on television and in gossip columns, was now equally unavoidable in his books.

After Armies of the Night, it’s hard not to see Mailer as the subject of each of his works. He was alternately Menenhetet and Ramses II in Ancient Evenings; Jesus Christ in The Gospel According to the Son; and Adolf Hitler in The Castle in the Forest, wherein, Mailer writes, the Devil himself inhabits his father’s seed at the moment of conception. In The Executioner’s Song, which to my mind is Mailer’s masterpiece, he embodied every character—from the killer Gary Gilmore, who declined to appeal his state-ordered death sentence after murdering two people in Utah, to his naive lover Nicole, to Lawrence Schiller, the opportunist who strenuously reported the story and gave all his material to Norman Mailer, who appears in the book, attempting to make sense of Gilmore’s story but capable only of presenting the facts, for the first and only time in his career, entirely without comment.

Of course, Norman Mailer was both a writer and a real person, and Mr. Lennon’s book is a detailed, if overly repentant portrait of a man so obsessed with his own image that he managed to disappear into his work. It’s telling that Mr. Lennon’s biography becomes very good when he, Mailer-like, appears as a character in it. He goes simply by “Lennon.” As the book progresses, Mailer’s persona and self-narration are grounded in a deteriorating corpus. His knees give out, and he has to walk with two canes. His teeth fall out of his infected gums. Mr. Lennon is with Mailer in his last weeks, and describes beautifully the great philanderer’s last drink of rum. His breathing tubes got in the way. In the end, almost inevitably, the only thing intact is his mind.

OVER THE COURSE OF writing this article, I went back and read my thesis in its entirety. It was, as I had suspected it would be, not very good. The transitions are sloppy, and the argument is tenuous and hard to follow. I did, however, include a wise epigraph, from Virginia Woolf’s “A Sketch of the Past.” I’ll spare you Mr. Lennon’s unconvincing apologies for Mailer’s blanket dismissal of feminism, but, even setting that aside, this was still a strange choice. (“I’ve never been able to read Virginia Woolf,” Mailer writes in the essay “Quick and Expensive Comments on the Talent in the Room,” happily reprinted in Mind of an Outlaw, where he trashes not only his contemporaries but also his influences.) I think Mailer, if nothing else, always fearless, would have hated it:

“Was I looking in the glass one day when something in the background moved and seemed to me alive? I cannot be sure. But I have always remembered the other face in the glass, whether it was a dream or a fact, and that frightened me.”

mmiller@observer.com