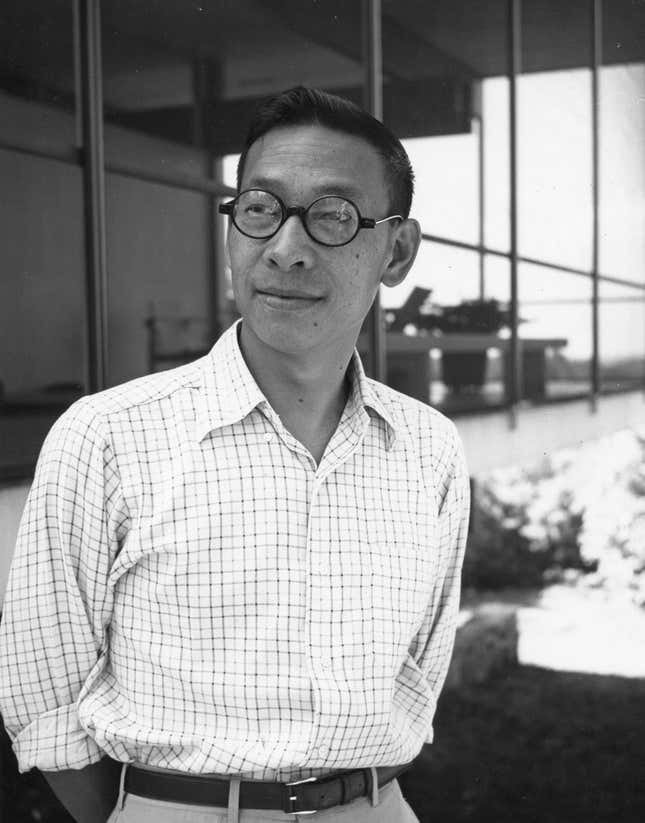

The work of I.M. Pei, one of the world’s most respected architects who passed away yesterday (May 16) aged 102, has for decades defined what it means to at once blend and distinguish cultures, to draw on diverse influences while staying true to one’s roots.

It was a question and challenge that Pei, who first arrived in San Francisco in 1935, grappled with starting from his college days.

A banker’s son, Pei was born in Guangzhou on April 26, 1917 and enjoyed a comfortable upbringing in a well-to-do family. He decided to attend college in the US, and enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, subsequently transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he graduated with a bachelor’s in architecture in 1940. Conflict at home and the looming threat of a Communist revolution convinced him to stay in the US, and Pei headed to Harvard University.

As a student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Pei studied under Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, two of the foremost Modernist architects of the day. He looked up to them both, but didn’t quite agree with Gropius’ claim that the spread of industrialization would create a single, global style of architecture.

“What about the relationship between history and architecture; between culture and architecture; climate and architecture?” Pei recalled asking Gropius, as detailed in a biography of the architect. “It was at that moment that I said I would like to prove something to myself, that there is a limit to the internationalization of architecture.”

Pei ended up writing his master’s thesis on this very topic—the importance of a country’s culture and history for architectural design. He created a plan for an art museum in his old hometown of Shanghai, giving it a Modernist cubic design but surrounding it with small gardens to bring out its Chinese character. It struck a chord with Pei’s professors, and Gropius even regarded it as the most important thesis project produced by a School of Design student.

Pei never shied away from his Chinese roots.

“I returned to China to visit family in the 1970s, nearly 40 after I departed the country,” Pei wrote in an article (link in Chinese) for the People’s Daily newspaper in 2004. “I feel that China is in my blood no matter where I live. China is my root.”

Yet he was also straightforwardly honest about the challenges of being an architect with multiple identities. Spending time in China after so many years away, he realized how little he understood about the country.

Designing the Fragrant Hill Hotel, located just outside of Beijing and completed in 1982, was the “most tortuous thing I’ve ever done, because I have to deal with a system I don’t understand,” Pei told the New York Times (paywall).

”I had to learn a lot, not about Chinese architecture, but about Chinese history all over again, how people live and their cultural traditions, and try to see what’s still alive after the Cultural Revolution and find out what roots are still living and graft them on,” he said. But he also wanted the hotel to inspire Chinese architects to draw inspiration from their own roots, instead of borrowing from the West.

Still, Pei wrestled with how to reconcile his dual Chinese and American identities, constantly navigating the “gaps between cultures,” as he once put it. In a 2010 interview with the Financial Times (paywall), Pei described his architecture as “not consciously Chinese in any sense.” It’s a sentiment that has its origins in his master’s thesis, when Pei decided that his design needed to reflect Chinese culture in some way, without resorting to widely recognized Chinese architectural details.

“I’m a Western architect,” he said in the interview.

On Chinese social network Weibo, people mourned the death of Pei by posting about him under the hashtag (link in Chinese) #Ethnic Chinese master architect I.M. Pei has passed away#.

Other buildings designed by Pei in China include the Suzhou Museum, Hong Kong’s Bank of China building, and the Macao Science Center. In Taiwan, Pei designed the Luce Memorial Chapel at a university in Taichung.

“I believe that I.M. Pei is a unique figure for every Chinese architecture student—the very idea that could be such a world-renowned Chinese master of architecture in our teaching materials. I.M. Pei is Chinese American, not an ABC (American-born Chinese). He grew up with Chinese culture. The fact that I.M. Pei was hailed as an undisputed master in America and the global architectural arena at a time when Chinese people were viewed negatively is truly rare and remarkable,” one writer wrote on Weibo (link in Chinese).

Pei’s stature and achievements around the world also inspired generations of Asian architects.

For Vicky Chan, the vice-president of the Hong Kong chapter of the American Institute of Architects, Pei gave him the confidence that, as a racial minority studying in New York, he too could achieve something.

“If someone else had made it, especially I.M. Pei, I do think I have a chance,” said Chan, who has in recent years taught Pei’s designs to young children through his non-profit organization, Architecture for Children.

And it wasn’t just architects who looked up to Pei. Jiayang Fan, a writer for the New Yorker, tweeted about Pei’s importance as a role model for other Asian immigrants in the US.

Pei’s life also traced the contours of America’s history of immigration and its interaction with international relations. He and many in his generation of fellow students were granted citizenship in the US in part because the new Communist government in China was pushing for overseas Chinese to return to the homeland, prompting the US to entice them to stay as a strategic move in the intensifying Cold War.

In her book The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority, Madeline Hsu wrote: “I. M. Pei’s life story surfs astride the shifting ideological, political, and legal tides that advanced the integration and visible successes of Chinese.”