At one time, nationally-acclaimed poet Carl Sandburg was so popular in Connecticut that even his goats made the news. After his death in 1967, some of Sandburg’s herd was sold to a kennel in Washington, Connecticut. The goats– Babette, Coty, and Tenu–were eventually returned to North Carolina when Sandburg’s home became a national historic site.

At one time, nationally-acclaimed poet Carl Sandburg was so popular in Connecticut that even his goats made the news. After his death in 1967, some of Sandburg’s herd was sold to a kennel in Washington, Connecticut. The goats– Babette, Coty, and Tenu–were eventually returned to North Carolina when Sandburg’s home became a national historic site.

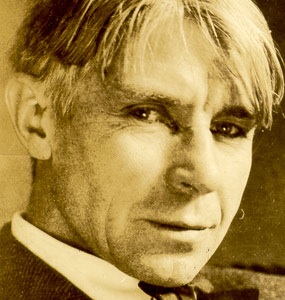

Today, however, if Sandburg is known at all by the general public, it is only as the white-haired old man who strummed a guitar and dubbed Chicago the “city of big shoulders.”

Carl Sandburg was, and still is, the people’s poet. He deserves a revival, especially in Connecticut where he had so many significant ties. But the reintroduction of his work can’t be a sanitized version of the original. It must include Sandburg the authentic radical (from the Latin, “coming from the root”). His collected folk songs and performances are treasures from America’s grassroots. His poetry offers a powerful critique of economic exploitation.

Born in 1878 to Swedish immigrants, Carl Sandburg was a working class boy who never forgot his roots. His father was a blacksmith for the Chicago railroad who took part in labor causes, including strikes. Sandburg recalled these formative events and considered himself a “partisan” who “took a kind of joy in the complete justice of the strikers.” He was ten years old.

Born in 1878 to Swedish immigrants, Carl Sandburg was a working class boy who never forgot his roots. His father was a blacksmith for the Chicago railroad who took part in labor causes, including strikes. Sandburg recalled these formative events and considered himself a “partisan” who “took a kind of joy in the complete justice of the strikers.” He was ten years old.

In his twenties Sandburg was a regular contributor of news and poetry to the International Socialist Review (ISR) and other prominent liberal and radical magazines. With his work for the Chicago Daily News he honed his skill as a reporter who wrote in the language of the working class.

In true muckraking tradition Sandburg exposed the 1915 Eastland steamer tragedy on Lake Michigan. The ship capsized, killing 800 workers on their way to a company picnic. Sandburg discovered that the Seamen’s union had for years protested the lack of ship safety regulations and quality inspections. He further revealed that the “picnic” was a mandatory event: you bought a ticket or you might lose your job.

Connecticut Visits

The College Club of Hartford may have been the first to invite Sandburg to our state. On February 3, 1922, he performed at the Center Church House on Gold Street. His lecture was entitled “Is there a New Poetry?” (Tickets could be purchased for one dollar at Mitchell’s Book Shop around the corner from the church.) Sandburg recited “The Windy City,” which had not yet been published, and sang some of the many folk songs that eventually appeared in his collection The American Song Bag.

The College Club of Hartford may have been the first to invite Sandburg to our state. On February 3, 1922, he performed at the Center Church House on Gold Street. His lecture was entitled “Is there a New Poetry?” (Tickets could be purchased for one dollar at Mitchell’s Book Shop around the corner from the church.) Sandburg recited “The Windy City,” which had not yet been published, and sang some of the many folk songs that eventually appeared in his collection The American Song Bag.

In January, 1932, Sandburg gave readings at Hartford’s Weaver High School, Bulkeley High and West Middle School for several thousand students, faculty and members of the public.

He spoke frequently at Wesleyan University and received an honorary degree there in 1940, the year he won his first Pulitzer Prize for Lincoln: The War Years. Sandburg shared the stage in Middletown with Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas and artist Grant Wood. A few days later he was in New Haven, receiving another honor from Yale University along with New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and philosopher Paul Tillich.

The poet’s body of work was widely known and celebrated throughout the state: as each new book was published, it would immediately move up the charts at local booksellers. In November, 1948, Sandburg’s Remembrance Rock was on the fiction best-seller list of Hartford’s eight bookstores. By the 1950s Sandburg no longer toured the country, but his works were as popular as ever. In 1959, Bette Davis and her husband, actor Gary Merrill (who was born in Hartford), performed Sandburg’s work at Bushnell Memorial Hall.

Moral Compass

“I am with all the rebels everywhere. Against all those who are satisfied,” Sandburg once wrote. As far as he was concerned, there was a straight line from the early builders of the American nation to the 20th century radicals, socialists, and unionists with whom the poet associated. “For the writing of the Lincoln I knew the Abolitionists better for having known the IWW I knew Garrison better for having known Debs,” he wrote. In Sandburg’s view, modern-day rebels would become tomorrow’s heroes.

Sandburg supported the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or the Wobblies) and his admiration for this radical union frequently appeared in his writing. Sandburg’s first three published collections, Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920) are full of IWW references, along with sympathetic portraits of immigrants, farmers, factory workers and the poor. He considered himself “an I.W.W. without a red card.”

Sandburg supported the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or the Wobblies) and his admiration for this radical union frequently appeared in his writing. Sandburg’s first three published collections, Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920) are full of IWW references, along with sympathetic portraits of immigrants, farmers, factory workers and the poor. He considered himself “an I.W.W. without a red card.”

The notion that Sandburg’s political leanings were just a symptom of youthful rebellion is contradicted by, of all people, J. Edgar Hoover. The FBI collected intelligence on the poet for 40 years. A newspaper exposé in 1987 revealed the extent to which Hoover kept tabs on Sandburg and all his affiliations that might be “communist front” activities. Sandburg was in good company: the FBI also had files on Ernest Hemingway, Pearl Buck, William Faulkner and 130 other famous American writers. Sandburg, however, survived the 1920 Red Scare and the Joe McCarthy years, anti-communist witch hunts that ruined the careers of other artists and writers.

He earned a reputation as a political and moral compass for many people in public life. As Secretary of Welfare in the Kennedy administration, Abraham Ribicoff considered Sandburg’s Lincoln an inspiration. Connecticut Senator Lowell Weicker quoted Sandburg during the Watergate hearings to encourage Richard Nixon to voluntarily testify before Congress. The Harlem renaissance poet Langston Hughes called Sandburg “my guiding star.”

Wallace and Wilbert

Sandburg counted a Connecticut governor as his friend. Fellow poet and Wesleyan faculty member Wilbert Snow knew Sandburg for fifty years. Snow was elected Connecticut Lieutenant Governor in 1945. He served as governor for thirteen days when sitting governor Raymond Baldwin resigned to take his newly-elected position in the U.S. Senate. Snow said Sandburg “found poetry not among the rills and rivers of the countryside but in the smokestacks of the city.” Sandburg once told Snow that he “cried for an hour” after he finished writing his six-volume Abraham Lincoln biography. Some years after completing the Lincoln work Sandburg wrote: “Poets cry their hearts out. If they don’t they ain’t poets.”

Sandburg counted a Connecticut governor as his friend. Fellow poet and Wesleyan faculty member Wilbert Snow knew Sandburg for fifty years. Snow was elected Connecticut Lieutenant Governor in 1945. He served as governor for thirteen days when sitting governor Raymond Baldwin resigned to take his newly-elected position in the U.S. Senate. Snow said Sandburg “found poetry not among the rills and rivers of the countryside but in the smokestacks of the city.” Sandburg once told Snow that he “cried for an hour” after he finished writing his six-volume Abraham Lincoln biography. Some years after completing the Lincoln work Sandburg wrote: “Poets cry their hearts out. If they don’t they ain’t poets.”

Hartford author and poet Wallace Stevens met Sandburg in their early Chicago days. The famously reserved vice president of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company so impressed Sandburg that he dedicated the poem “Arms” to Stevens. In the poem Sandburg learns that the French impressionist Renoir (who died in 1919) kept a rigorous daily schedule of painting despite arthritis that seriously crippled his hands. In the last stanza Sandburg writes that when the two poets met again “I will ask you why Renoir does it / And I believe you will tell me.” This tribute to Stevens was not published until 1993.

Sandburg described Stevens (but not by name) in a newspaper series that recorded his 1932 national lecture tour. “I sat in the home of a Business-man author (there is such an animal!) in Hartford Conn.,” Sandburg wrote. He described Stevens as “conservative in his political and economic views,” concerned about how “lady luck” dominated the fate of the middle and working class as they struggled through the Great Depression.

Is Sandburg Still Relevant?

Sandburg’s early detractors labeled his poetry “propaganda” and warned that poets had no place focusing on issues of the day. In later years, his Work was called dated, almost quaint. But there will always be ideas and events that need a poet’s anger and passion.

In December, 2012 in Newtown, Connecticut, twenty-six elementary students and staff were shot to death at the Sandy Hook Elementary School. The killer was armed with a Bushmaster semiautomatic rifle and a Glock pistol. He fired 154 bullets in five minutes.

Carl Sandburg, long dead, responded to the killings.

Just a month after the shootings, a previously unknown Sandburg poem was discovered. Found by accident at the University of Illinois, the piece is entitled “A Revolver.” It begins:

Here is a revolver. / It has an amazing language all its own. / It delivers unmistakable ultimatums. / It is the last word. / A simple, little human forefinger can tell a terrible story with it.

The poem ends: “And nothing in human philosophy persists more strangely than the old belief that God is always on the side of those who have the most revolvers.”

Guns, violence, and war are haunting subjects of Sandburg’s poetry. But they are balanced with the courage and hope of people forced to cope with tragedy and hard times. He writes in “The People, Yes:”

The people know the salt of the sea / and the strength of the winds / lashing the corners of the earth. / The people take the earth / as a tomb of rest and a cradle of hope. / Who else speaks for the Family of Man?

We have Carl Sandburg to thank for lasting portraits of ordinary Americans, as true today as when he first introduced them to us.

A version of this story appeared at connecticut history.org, a project of CT Humanities.

[…] https://shoeleatherhistoryproject.com/2015/04/17/carl-sandburg-peoples-poet/ […]