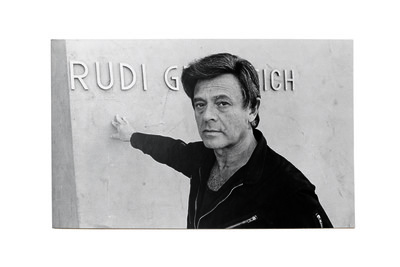

The life and times of serial avant-gardist Rudi Gernreich.

By Tim Blanks

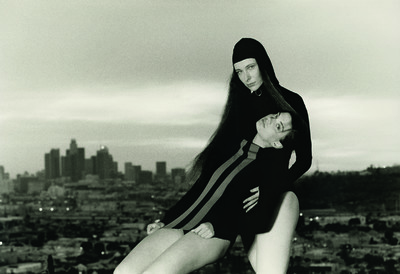

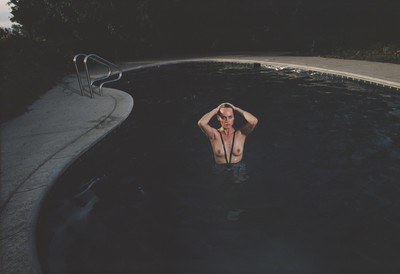

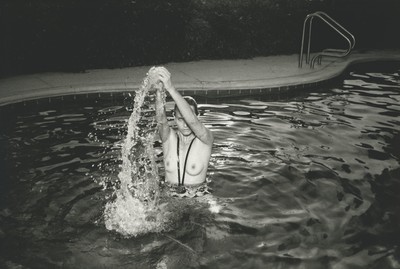

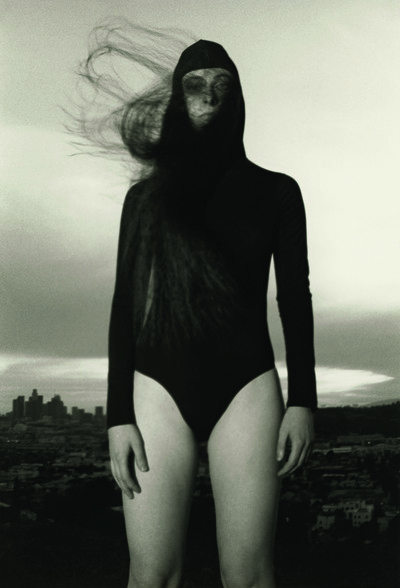

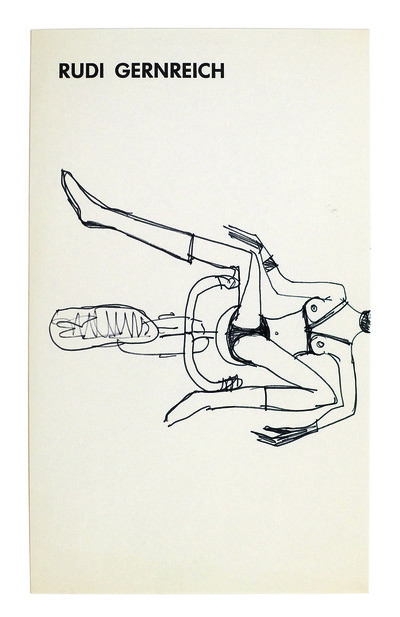

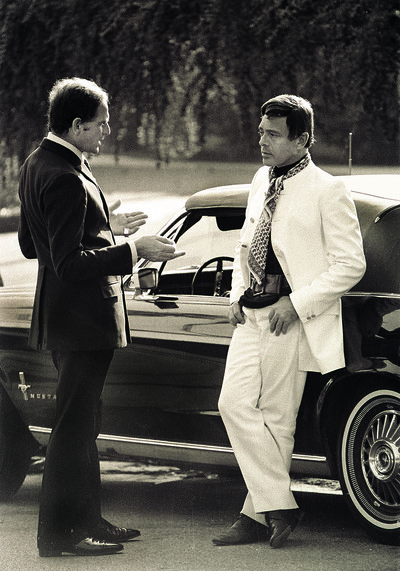

Photographs by Robi Rodriguez

Styling by Karen Langley

The life and times of serial avant-gardist Rudi Gernreich.

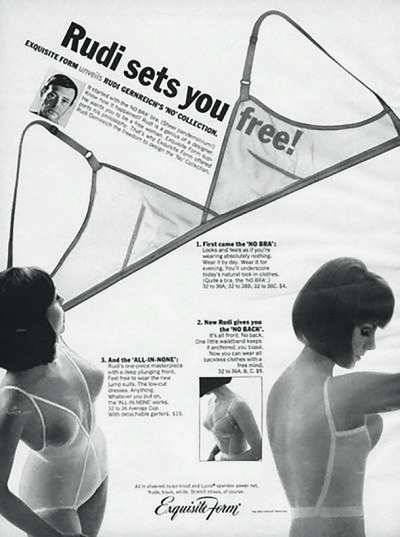

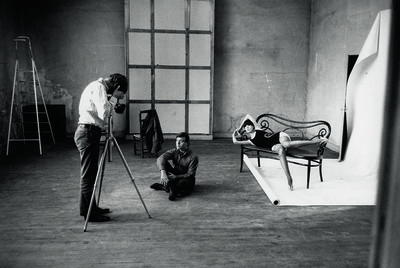

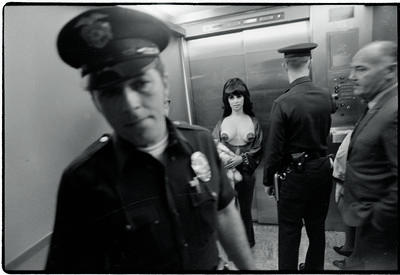

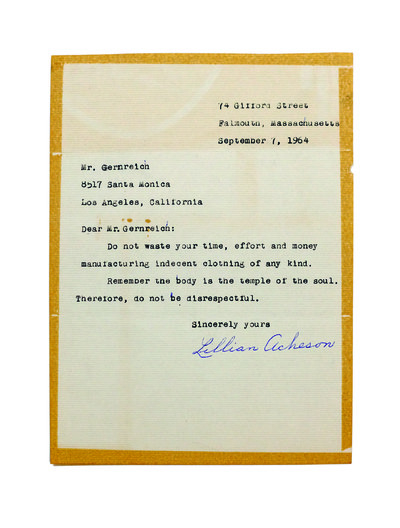

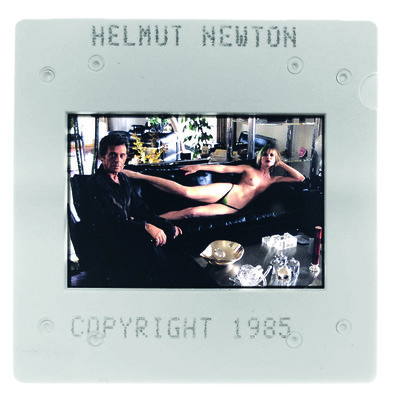

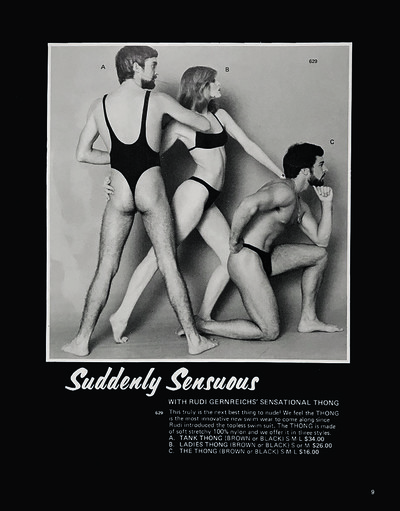

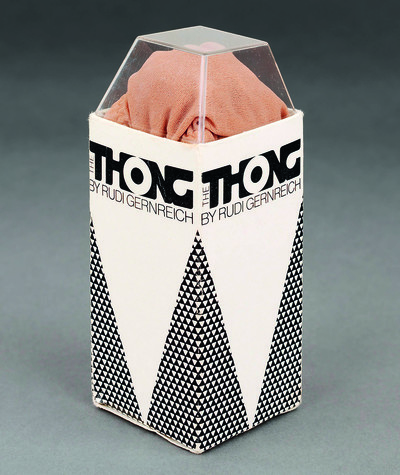

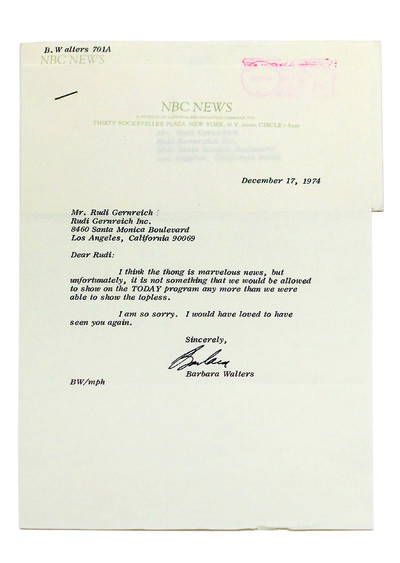

There was a time when Rudi Gernreich was the most famous designer in the world. When he launched the monokini, his topless bathing suit, in 1964, even the Vatican weighed in with an opinion. ‘An enemy of the church,’ railed Pope Paul VI. But that particular cause célèbre wasn’t the only one over a three-decade career in which Gernreich literally reshaped women’s fashion with his elevation of knitwear, transformation of swimwear, and, more than anything, invention of the ‘no-bra’ bra, without which it would be hard to imagine contemporary womenswear. Then there were minis and cut-outs and thongs and pre-Calvin briefs and boxers for women, a whole repertoire of liberated body-consciousness years and years before it occurred to anyone else. Rudi could even lay claim to the first fashion video, when his clothes were the focus of Basic Black, a seven-minute short created with his iconic muse, actress Peggy Moffitt, and her photographer husband William Claxton in 1967.

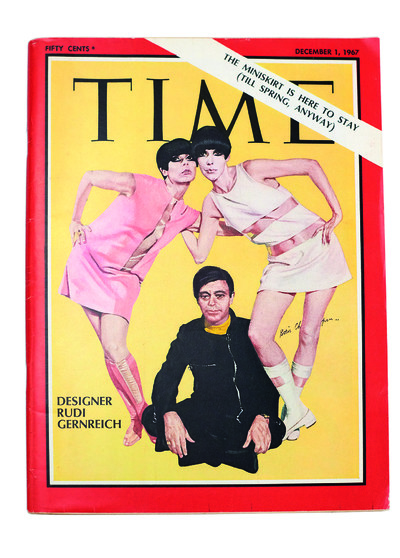

Gernreich wasn’t a prophet without honour. Awards came often in the 1950s and 1960s. The monokini was tucked away in a 1965 time capsule between the Bible and the Pill, definitive of its era. In 1967, Gernreich made the cover of Time, one of just a handful of designers to receive that accolade in the magazine’s 96-year history (others include Schiaparelli, Dior and Armani). The following year, he took a sabbatical, however, saying he was over fashion. For its January 1, 1970 issue,

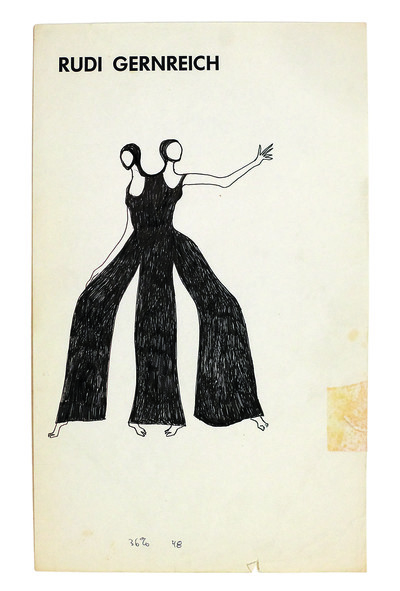

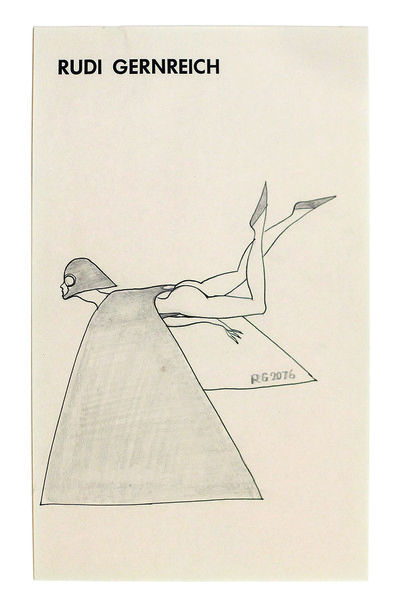

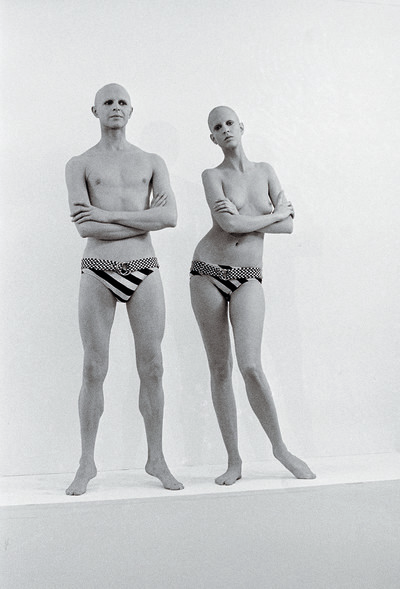

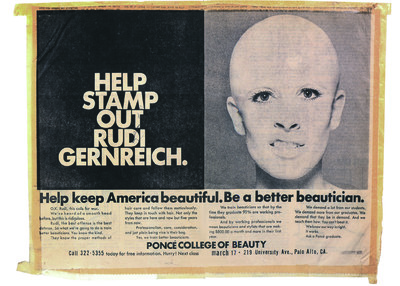

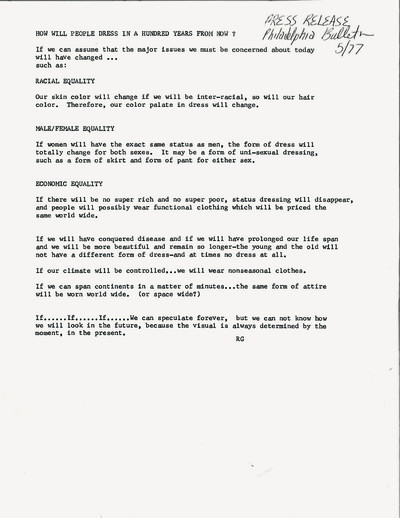

Life asked Gernreich to contribute his vision of fashion in the year 2000. He offered drawings of a man and woman stripped to barest, genderless essentials. ‘I see unisex as a total statement about the equality of men and women,’ he declared. ‘Their different sexual natures no longer need the social support of differences of dress. Unisex reveals nature, our common humanity. It doesn’t hide or confuse it.’ Gernreich was invited to realize his vision at Expo ’70 in Japan. His models, shaved of every strand of hair on their bodies, were dressed identically in tunics and leggings from past collections. He wanted to make the point that the ‘newness’ of the clothes was irrelevant: ‘Who puts them on makes them what they are.’ And, equally, who takes them off – the models stripped naked.

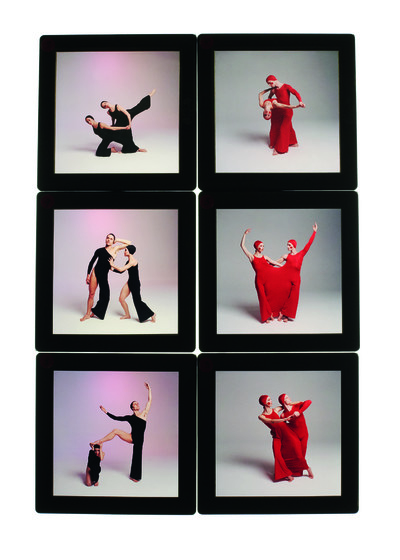

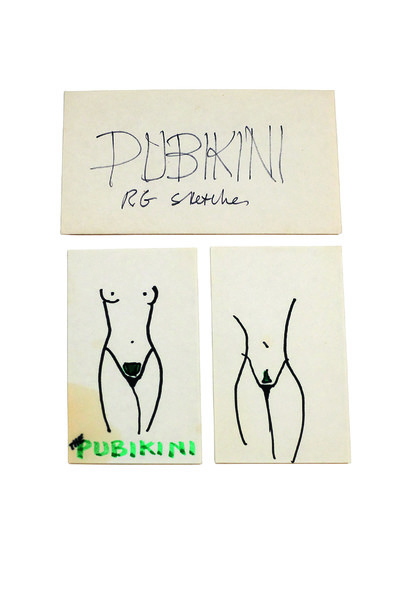

After this ‘anti-fashion’ statement, Gernreich dabbled throughout the 1970s: designing furniture, homewares, costumes for his friend Bella Lewitzky’s ballet company, conceptualizing the thong as a response to California banning nudity on beaches, even making soups for his friend Wolfgang Puck’s restaurant. Maybe this resumé created a dilettanté-ish stratum between Gernreich’s radical past and his place in posterity. For whatever reason, by the time he died of lung cancer in April 1985, he had already been consigned to another era.

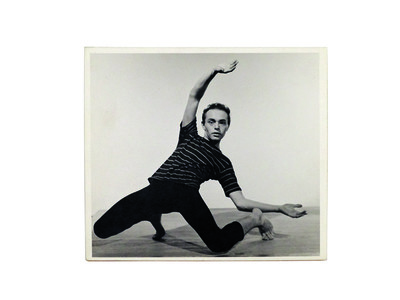

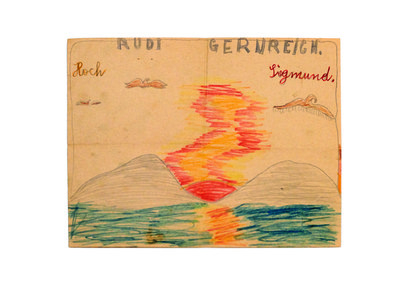

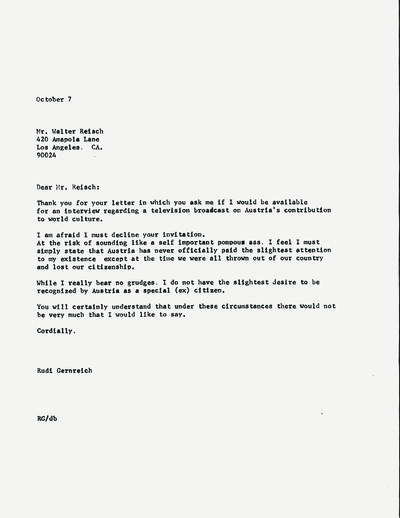

We can waste time by reasoning why, or we can diligently apply ourselves to some reputation recuperation. Gernreich is ready for a new prime time. I heard a delicious rumour that Nicolas Winding Refn wants to film his life story. Well, who wouldn’t? Born in 1922 into a Jewish family in Vienna, Gernreich was exposed to fashion early on through his aunt’s dress shop. He was 12 when she took him to Paris, where he went to a Balenciaga couture show. That obviously lingered in his psyche, almost as much as the influence of the Wiener Werkstätte, all around him in Vienna. When the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938, Gernreich and his mother fled to the United States (his father had committed suicide when Rudi was eight) and settled in a Los Angeles community of Viennese exiles. He was an art student, until he became captivated by dance, joining the Lester Horton Dance Troupe, which was a hotbed of left-wing radicalism. That gelled with Gernreich’s own outsider political and artistic sensibilities. Through Horton, Gernreich met Harry Hay, and, in 1950, the pair founded the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest LGBT organizations in North America.

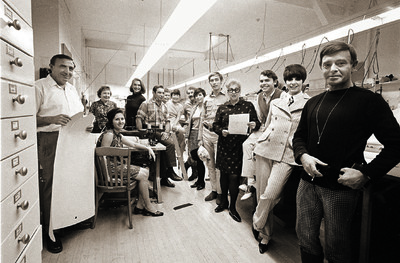

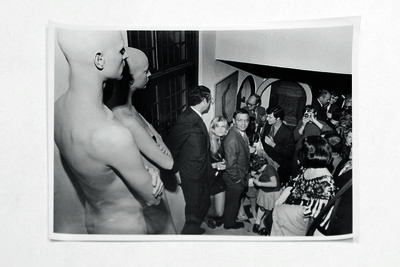

‘You are what you decide you want to be,’ Gernreich said in 1970. It might be that his activism – his commitment to equality, diversity, sexual expression and LGBT rights, made manifest in his bequest to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) – is one way to highlight his relevance. Another is his deep-rooted engagement with the arts community in Los Angeles, which embraced him. There is a famous photograph of the city’s art elite posed on the steps of the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art in 1968; Rudi is the only fashion designer. Try to imagine something similar happening at the same time on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

‘Rudi spoke of his childhood in Vienna, of being turned on by the glimpses of flesh of women’s thighs between their stockings and their garters.’

Los Angeles was both a blessing and a curse for Gernreich. The physical environment was ideal for his open-minded, body-conscious aesthetic, but the city was also marginal in the fashion and, slightly less so, the art world. That may have hindered his place in posterity, but what’s more enlightening is to trace Gernreich’s influence, from his groundbreaking knitwear in the 1950s onwards. His disciples are an interesting group. Yves Saint Laurent was a fan (Rudi pioneered the sheer looks and androgyny that gilded YSL with scandal). I would hazard that André Courrèges was, too. Tom Ford’s career-defining pieces at Gucci owe a debt to Gernreich’s cut-outs. Silk jersey clasped by sculpted metal neckpieces and cuffs? More echoes of Rudi. Stephen Sprouse and Norma Kamali were clearly acolytes. The DNA of a very particular, strong line in American fashion derives from Gernreich.

German entrepreneur Matthias Kind is currently overseeing the revival of the Rudi Gernreich brand and clothing line. Meanwhile the Skirball Cultural Centre in Los Angeles is showing “Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich” until September. I’ve heard there is also a major exhibition planned for what would have been Rudi’s 100th

birthday in 2022 at FIT in New York. It would be wonderful to think that the then V&A curator James Laver was being unduly downbeat when he declared in 1964 that it would take ‘a century and a half’ for Gernreich’s monokini to be considered beautiful. Though, on second thoughts, being able to conceive of his relevance 150 years later could actually be construed as a major compliment to his enduring modernity.

After all, there was, is and will be no one like him.

Barbara Bain, actress: When I met Rudi in 1951, it was one of the sweetest meetings in the universe between two people. We were in the outer office waiting for Diana Vreeland at Harper’s Bazaar. I was modelling to pay for my dancing classes with Martha Graham. My agency had sent me to meet Vreeland, and I was terrorized by the whole idea. I walked in, and there was this pretty boy with a rail of clothes. Rudi had come in from Los Angeles, and LA designers were really special in New York. He said to me in a very shaky voice, ‘Would you like to see my things?’ I fell in love with what was hanging on the rack. Knitted fabrics, in bold colours, with a very clean line. They looked very much like they had come out of the modern dance world. I said, ‘This is great, you are going to do so well.’ And he hugged me and said, ‘You are divine and you are going to do well!’

So, there we were, these two skinny kids cheering each other up. So we always had that moment together, on the cusp of any kind of big career. And when Rudi came to New York with his line every year, he would call me and I would be in the show for him.

Billy Al Bengston, artist: We would have met around 1958 or 1960, through Pat Faure. She was probably the most sophisticated person in California at that time; she was a blender. She brought me to Rudi. He was an unusual cat, a handsome little fella when most of the designers weren’t very attractive. He dressed in black, which was unusual for California at that time. Very individual, sort of like a European existentialist. If you talked about Rudi, people would say, ‘Oh, the guy who wears all black.’ I just thought, who would wear those uncomfortable clothes in California? It was definitely not Californian. Black. Too fucking hot. And you know, we weren’t all nocturnal, a lot of things happened during the day. Wearing black during the day, unless you’re a Bedouin, doesn’t cut it. And he had horrendous dandruff. I once mentioned it to him: ‘Rudi, you got to stop wearing black or get rid of your dandruff.’ He was never a glamorous figure to me; he was a little mouse as far as I was concerned. He never left the house without his wig on.

Tim Blanks: Did you ever see him without his wig?

Billy Al Bengston: Yeah, quite by accident.

Tim: What he did look like without it?

Billy: He looked like Rudi without his wig.

Layne Nielson, Rudi Gernreich’s accessories designer: Rudi was small, only 5’6”. Some people have described him as elfin but I wouldn’t go that far. He had this captivating personality that could win over everybody, an innate Viennese good humour. I was from Utah and had never met anyone from Europe until I went to Los Angeles. He was an exotic and sophisticated European. He always dressed completely differently from anybody else, starting from when he was a child, and his mother just let him dress in whatever he wanted. One of his cousins told me that he always dressed up in bizarre outfits, unlike any other child in Vienna. Rudi had his own idea about how he wanted to present himself; I guess he would look in the mirror and find it appealing. There are photographs of him about the time when I met him in 1958 and he was wearing conventional suits, so he looked like he would fit in with everyone else. But when you saw him in person in that outfit, he would

look completely different because of his short stature and the innate grace of the way he moved. Some people have said it was a dancer’s grace, but he was never a very good dancer. He was just very light on his feet. There was nothing effeminate about him, though, absolutely nothing like that.

‘He dressed in black, like a European existentialist,not at all Californian. If you talked about Rudi, people would say, “Oh, the guy who wears black.”’

Billy Al Bengston: I liked Rudi personally. He was a goofy little guy. He was as tight as a tick but he was generous compared to everyone else. I was about as

crapped-out broke as you could get and I did a couple of jobs for him. He had some money. You had to have money to run in his crowd. I think if they had parties, Peggy Moffitt took over. Moffitt was a great lip; she was a magnificent social person.

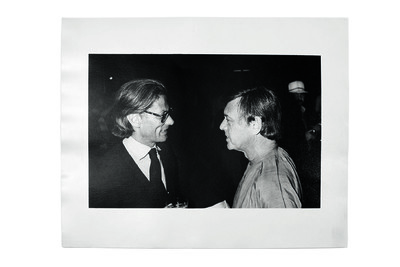

Irving Blum, gallerist: I became very friendly with Bill and Peggy Claxton in the late 1950s, early 1960s, and she brought Rudi into the gallery. He was really excited about a lot of the people I was showing: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, and I remember that he was particularly taken with Ellsworth Kelly.

Billy Al Bengston: I was the only one who knew Warhol. He was a nice creep. I liked him a lot. But we had very little in common. Name-fucker – I think that was a term that was popular then. But you got to realize at that time, we would just go to the coffee shop down from the Ferus Gallery and drink coffee and that would be about it. Rudi wasn’t part of that. He was a hardworking son of a gun. He didn’t care about any of that. I would say he was about as devoted as you could get to his profession. Yet light-hearted, too.

Irving Blum: I thought Rudi was enormously sensitive and bright. He wasn’t very forthcoming, but when he was, it was absolutely worth listening. He had an innate understanding of what it was I was up to. He responded to the modernity; to his eye, it was extremely fresh. I really appreciated that and became very fond of him. Rudi didn’t really buy art from me, maybe a drawing or two. I remember he liked John Altoon a lot. I was the first person to show Warhol, so Andy came out a few times. He came especially for the Duchamp show at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963 and Rudi was there. So they could have met there or at the gallery. I didn’t see Rudi that often. Generally, when he came, it was with Peggy, who was fabulous. I adored her and I adored her husband, Bill. And Rudi kind of came in their wake. I knew what he was doing in fashion was extremely radical; I loved it. Jimmy Galanos used to come around as well. He was interested in what I was doing, but not in the same way Rudi was. He was completely fascinated by art activity and I always thought he had a radical voice. Galanos and I never talked about Rudi, but I’m sure he was aware of him. Everyone was.

Elizabeth Saltzman, fashion editor: My mother always wore Rudi. She was wearing him in the 1950s. She was part of that whole crew. Before I was born, she was an editor at Glamour, and a stylist. Rudi to me was equal to the coolness of my mom. It was just normal life for us, except my mom was different from every other mother ever. She didn’t make my clothes, or bake cookies, or come dressed in Lily Pulitzer. My mother had short hair, and wore knitted swimwear at the beach in really cool yellows and reds, and turtleneck swimsuits and cut-outs. And all that was Rudi. We are a minimalist family; we keep nothing, but she still has two of those bathing suits tucked in her bathing suit drawer.

Layne Nielson: The word Californian always seemed to be attached to his name, because the Californian lifestyle was so different to anyplace else in the country; it allowed a more casual kind of dressing. It was a style that was recognized in New York as something completely different. Back then, Vogue would run entire issues called ‘Californian Style’. Rudi was influenced by Claire McCardell because he admired her all-American attitude. She paid no attention to what was coming out of Paris, which every other designer in the United States was copying. Norman Norell, for example, said he didn’t do anything until he saw what Paris was doing. But Claire McCardell struck out on her own. I think her clothes were gaudy beyond belief, so in that respect they were the exact antithesis of Rudi’s because his were always very dramatic. He was influenced by the Wiener Werkstätte. Surprisingly, he also said he admired Balenciaga, but look at Balenciaga at his best, when he was cutting some of those big cape coats that apparently have no seams, and you can see why. Rudi understood the simplicity.

‘When the monokini hit in 1964, Rudi became an international sensation overnight. It was all media chaos, which is exactly what he wanted.’

Excerpt from a phone conversation between Michèle Lamy, Rick Owens and Tim Blanks

Tim Blanks: Rick, as a designer from California, do you consider Rudi a Californian designer?

Rick Owens: Was he Californian, really, or was there a Viennese influence?

Tim: Well, he was inspired by the Wiener Werkstätte, for sure, but he always called himself a Californian designer.

Rick: He was happy to say that because California was exotic to him, the way Europeans are exotic to us. I think it is kind of that whole Europe-meets-California thing. That has always been my fascination. I think it has something to do with his aesthetic too, but in reverse. My whole shtick is that I’m a Californian working in Europe, while he was an Old World European working in California.

Layne Nielson: I met Rudi in 1958. I had just moved to Los Angeles from Utah where I grew up. I was fleeing home and a friend offered me a place to sleep and he got me a job at the UCLA library, printing numbers on the spines of books. It was mostly art students, but one of the people sitting next to me was not an art student, but a very sophisticated European dressed in a suit. It turned out he was Rudi’s cousin, Paul. One day he mentioned to me that he had a cousin who was a very famous designer, and wheels started to turn in my head. I didn’t know what I was going to do in Los Angeles; I certainly hadn’t thought about the clothing industry. I thought I was going to be a musician or something like that. So, I said to Paul, do you think I could meet your cousin? A few days later, Paul said to me, Rudi would be happy to meet you. I cannot imagine what Paul had said to Rudi. He was already very famous at that point, and here I am, a nobody from the sticks and he is agreeing to meet with me. So, I quickly turned out some sketches overnight and I go to meet him. His workroom was in Beverly Hills and he took me for lunch at Frascati, one of the trendiest European-style restaurants in town. It wasn’t very far from the Walter Bass workrooms. I showed him the sketches and he said, ‘If you are interested in learning to make hats, I will use them in my collection.’ A kid from Utah learning to make hats? It was just too like a fantasy land or something. But he said he had a friend who could teach me the basics, and that’s how it started. I made hats for his shows, little pillbox hats, things like that on a freelance basis, until I went into the army in 1961. When I got out of the army in 1963, I contacted Rudi who said, ‘Come back and work with me’, so I went to Los Angeles and started full-time in April 1964.

The monokini had just broken on the news. The studio, everything around him, was a hive of attention and activity and media chaos. There he was, already a famous designer in the United States and then overnight, he became an international sensation. That was what Rudi wanted. And as he got more famous, his ego swelled, which just emphasized what was already part of his character: he always thought he was right about everything.

Léon Bing, muse and model: I came just after Peggy had gone to London to be an actress. I guess you could call me a muse. I remained so even when Peggy

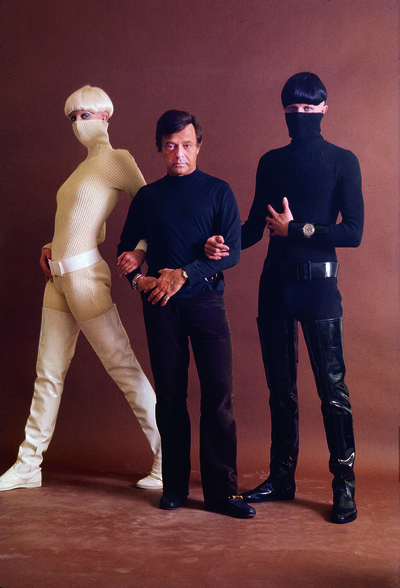

came back. Then Rudi had two muses. We were both on the cover of Time. As a muse, all I had to do was show up and bring my cheekbones. Some clothes were being made on me; some were made on Peggy. It must have been 1965 when Rudi and I first met. I was doing that big show at the Met they had every year, where every swell in town showed up in their finest and the main floor was emptied and that’s where about seven models each wore something from the museum archive. Another model came up to me and said to me that Rudi Gernreich wanted someone who looked like a spy. I did fit that bill – I had a black Louise Brooks bob. So I went to see him in his hotel suite, at the St. Regis I believe it was. He didn’t have a showroom; he rented hotel suites. I’d heard his name, though I didn’t know his clothes terribly well. I tried the first dress and I thought, ‘Oh my God, these are perfect.’ I knew from that moment that Rudi was a revolutionary, and I knew about clothes early on, because my mother had all her clothes made by Adrian. Rudi’s dresses had built-in pockets, because he very much wanted the women who wore them to feel comfortable. I didn’t wear a bra and he loved that. He made the ‘no-bra’ bra to make it look as though you weren’t wearing one. After that we were together as artist and model forever after. Edie Sedgwick and Andy Warhol came to one of our first shows together. Warhol was very, very strange-looking and she was trying to look like him with the hair colouring. They were an odd duo.

‘Rudi wasn’t particularly political, but if he thought he was going to be at the forefront, he’d do something daring and radical.’

Marylou Luther, journalist: When I first met Rudi, he let me mispronounce his name as gern-RIKE. He never once corrected me. It wasn’t until I called his office one day and his secretary Fumi answered, ‘Mr. GERN-rick’s office’ that I realized my mistake.

Léon Bing: He and I got each other’s humour, a very dry, rather English kind of humour. He could make me pee with laughter. His husband, Dr. Oreste Pucciani, was the chairman of the French department at UCLA. He knew absolutely nothing about fashion and didn’t care. Oreste was very stern-looking, like a Roman emperor, but fortunately he liked me, and it was my great delight to make him giggle. Rudi talked a lot about his childhood with me, his adolescence in Vienna. He talked about being turned on by the leather chaps that working men wore, by the glimpses of the white flesh of women’s thighs between their black stockings and

their garters, both sensual and sexual. I remember him designing an outfit in which long woollen stockings went right to mid-thigh and then a good two inches of flesh before the hem of the skirt. No one was doing anything like he did. I remember a long dark blue dress I wore for evening, a very thin wool skirt, a cap-sleeved top in one layer of chiffon so sheer you could see not only the outline of the breast but the nipples, everything. It was beautiful. The closest comparison I can make is Balanchine, the great choreographer who adored women – Rudi loved women.

Marylou Luther: Rudi never discussed his sexuality with me, but I think it was one of many influences on his design. While he never outed himself, he was one of the founders of the Mattachine Society, a forerunner of the gay movement. From 1950 to 1952, he and Harry Hay, who founded the movement, were lovers. Gernreich resigned in 1953, along with other founders, over an ideological schism. That the man who tore up so many closets with his revolutionary clothes never came out of the closet himself says a lot about Gernreich and his times. Peggy Moffitt, his model-muse, explained it this way: ‘I don’t think it ever occurred to him to come out of the closet because he felt his sexuality was understood and that there was no way to hide it.’ Gernreich’s partner of 31 years, Oreste Pucciani, told me that Rudi told him that he didn’t reveal his sexuality ‘because it would be bad for business’.

Layne Nielson: Rudi was very, very private. He had never lived away from his mother until he moved in with Oreste in 1956, I think. They kept a very low profile. All of this business about Rudi being active in some kind of a gay-rights movement is absolutely false. It is true that he was one of the two co-founders of the Mattachine Society, but it wasn’t like a planned event. Harry Hay was such a rabble rouser and what attracted Rudi to Harry was his socialist and communist leanings, not the gay rights. And one night, Harry said he had an idea about doing all these things for gay rights and Rudi simply said, ‘Well I am with you 100%.’ And if Rudi had not said that, there would have been no Mattachine Society. He didn’t fund it; he was just there. It was only when Stuart Timmons resurrected Harry Hay that this whole false notion got built way out of proportion. I say again that it is absolutely true that Rudi and Harry Hay were the two founders of the Mattachine Society, but that is about all you can say.

‘That the man who tore up so many closets with his revolutionary clothes never came out of the closet himself says a lot about Gernreich and his times.’

Tim Blanks: There was a story I heard that Rudi paid the bail of the people arrested during the Stonewall riots in 1969, which, if true, was quite an incredible political gesture at that time.

Layne: He may have. Rudi always wanted to be out in front of something. He didn’t have a terribly active political mind, but if he thought he was going to be out in the forefront, and do something daring… His whole family were socialists. So that was just part of his DNA.

Tim: Do you think that made life difficult for him in any way in America?

Layne: I don’t think he would have let anything make life difficult for him, though his involvement with the communist stuff with Harry Hay did bring him very close to danger. It got him right up close to the House Un-American Activities Committee. That was Harry Hay’s big drum to beat, as it was with Bella Lewitzky and Lester Horton. That is when Rudi was dancing with Horton, and that whole group came under scrutiny. They certainly knew about Rudi, but he was not entangled with it, let me put it that way.

Irving Blum: The artists, by and large, had a real regard for what Rudi was doing, and he had every kind of entrée as a consequence. So when Peggy would

take him to an artist’s studio, they were always extremely respectful and open to him. I think they saw an extraordinary creativity. Whether he saw himself as an artist is an interesting question. That subject never came up. I always thought of him really as both designer and artist.

Larry Bell, artist and sculptor: I knew Rudi from the art scene at the Ferus Gallery where I hung around. Irving Blum or Walter Hopps introduced us. I had no other contacts with the fashion world, but I knew a lot of stylish people who dressed great. Billy Al Bengston and I used to haunt the thrift shops looking for nice suits and ties. Rudi invited me and Billy to his workshop; it was the first time I had been in such a studio. I was impressed with the number of people who were around his scene. He was a possible collector and that in itself was unusual. There were a lot of people in the scene but not very many that collected our works. He was one of the first people to buy a sculpture of mine. He never talked about his past with me. We talked about colours and textures and surfaces. I thought he was very cool and he was very soft spoken and funny. In general, the humour was totally silly. He was good at it and serious with his work, just like the other artists who were close to me. I recognized a kindred spirit. Rudi had a very quiet sense of being part of the underground. I don’t remember what I thought of the topless bathing suit in 1964, but I was astounded when I went to a showing at someone’s house and all the models were naked and had shaved their bodies completely.

Rudi Gernreich, press release for the Autumn 1968 collection, released in May 1968: The body is a legitimate dimension of human reality and can be used for a lot of things besides sex. Slowly, the liberation of the body will cure our society of its sex hang-up. Today our notions of masculine and feminine are being challenged as never before, the basic masculine-feminine appeal is in people, not in clothes. When a garment becomes sufficiently basic, it can be worn unisexually.

Issey Miyake, designer: Rudi had a very definite idea about clothing and how it extended to the human body. He clothed men and women in the same clothing; he was against clothing that defined one by one’s sex. Some call him a modernist – I am not sure. I can only say that he was a designer who was always thinking of new ways to express ideas about the human body using clothing. Rudi acted quickly on what came to his mind. I believe it is very important for a creator to have such a pure attitude.

Ed Ruscha, artist: I met Rudi in the late 1960s through Léon Bing, a model for many of his daringly original fashion statements. I would occasionally spot him driving his white Bentley (very slowly) to his shop on Santa Monica Boulevard near La Cienega. He would wear his own distinctly self-designed clothing. He could be stately and aloof, but at the same time remain a rather ordinary citizen. I cast him in a short movie I did with Larry Bell. Rudi played a roguish flophouse doorman who sneers and says, ‘’At’ll be two dollars.’ Here was an elegant man in real life playing a lowdown character who cleans his dirty fingernails with a screwdriver.

Léon Bing: I grew up with art and loved it. I knew most of the young emerging artists like Ed Ruscha and Larry Bell and Ed Moses. And Irving Blum had his gallery. I met Ed [Ruscha] when we all posed for the cover of Los Angeles magazine on the steps of LACMA, with every artist represented in the museum and, for some unknown reason, Rudi and me. I loved Ruscha’s work; he was holding one of his larger paintings that was in the museum, and I thought he was even better-looking than his art. I said to Rudi, ‘Go get him,’ he said, ‘I don’t know him’ and I said, ‘That’s never stopped you before.’ So he did, and that’s how I met Ed. And then Ed got a Guggenheim Fellowship and he ended up making a book and a movie with us all called Premium, as in the crackers. Rudi played a kind of bellboy in a fleabag hotel with old dirty trousers and a dirty T-shirt. Ed poured salad all over me; I was picking parsley out of parts of my body for days after we shot it. It was

a really fun, experimental time, almost anything went. Almost is the key word there.

‘Rudi had a very definite idea about clothing and how it extended to the human body. He was against clothing that defined people by their sex.’

Larry Bell: Ed Ruscha asked Rudi to play the part of a hotel-desk manager; his role was to act like a seedy guy in a seedy Hollywood hotel. He had to wear very funky clothes that seemed totally not Rudi. If I recall correctly, he was to chew gum rapidly while he talked briefly. I was always very comfortable around this famous man; he was easy to like. He enjoyed being around artists.

Layne Nielson: I wasn’t that involved with the art scene then. Those people were another world for Rudi. He was the only clothing designer who was accepted by the arts community on that level, at least in Los Angeles. He also was the only one who was included in surveys of prominent cultural people in Los Angeles. Life ran a large newspaper ad titled, ‘What does Los Angeles think about life?’ and Rudi was the only designer included with all these other prominent figures. He always thought of himself as an artist. That sort of explains why he had no interest in learning how to put a dress together. He had no clue how to construct a garment. Even after all the years of working with Walter Bass, he still didn’t know. If you look at his clothes, the good ones, they are like cookie-cutter cut-outs, there is practically no construction to them. They are a concept and the artist in him produced them. And other artists recognized that. I have a letter from Larry

Bell that he wrote to Rudi and he said, ‘It is nice to know that there are other people, such as you Rudi, doing what we are doing.’ There were a few journalists in the fashion industry who also understood that. I think one of them wrote that one of his patterns looked like a Matisse when it was laid out.

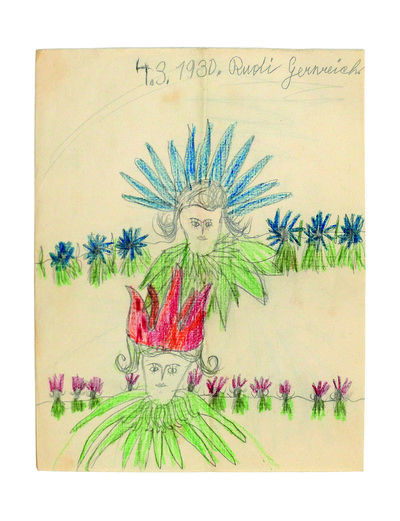

Cameron Silver, fashion historian and philanthropist: For sure, Rudi was an artist. I had a client who was aware that I had curated a Gernreich exhibition at MOCA several years ago, and she lived not far from where Harmon Knitwear was based. They had had a huge fire and someone had salvaged some of the original Rudi Gernreich fabrics, which she then sent to me. These textiles were art pieces, so graphic looking. And the typography of the scarves, the placement and manipulation of letters that was so distinctive, in the same sense that Katherine Hamnett created an iconic typography on her graphic T-shirts. Rudi never wanted the letters to say anything though, which I thought was quite interesting.

Marylou Luther: His relationship with the media was iffy. Several major magazines and newspapers refused to show pictures of Moffitt wearing his topless

bathing suit; others did not show photos of the two naked models he took to Expo ’70 in Japan. For me, Gernreich was a gift. To have someone that newsworthy in your own backyard, to have Q&A breakfasts, lunches and dinners with him was a godsend. Did I maintain my journalistic objectivity? I think I did; I hope I did.

Layne Nielson: We didn’t do many shows in LA because the market was smaller, there were fewer retail stores, and the press was in New York. And Rudi was interested in the press. That is why we would haul all this stuff to New York, three or four times a year. We showed there right up until the end of 1968 when he went out of business. The people he would show for were, for the most part, great fans. So were the big press people, from the New York Times, the Herald Tribune, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Then there were the other ladies coming from the provinces, Minneapolis or Detroit, who were there for the excitement of fashion week. And they would write that there was nothing like a Rudi Gernreich show because you never knew what you were going to see. There was always something they thought was outrageous. Then there were others who called him a kook.

‘He had no clue how to construct a garment. His clothes were like cookie-cutter cut-outs. But they were a concept, and the artist in him produced them.’

Barbara Bain: Rudi’s clothes were so strong and clean and different. They moved, they weren’t static at a time when everything else was fairly stiff. It was straight-line dresses and tight jackets. At the time I was modelling with Charles James, who was an extraordinary designer; he was called the Balenciaga of America. He would build designs that could stand up by themselves. But he wasn’t nice. I would stand there and get stuck with pins. All to pay for my dance classes!

Layne Nielson: His clothes would work on a 17-year-old and an 80-year-old. My aunt was in her 80s when she died and she had worn Rudi’s knit dresses every single day, and they had looked absolutely right. They were cut so simply that anyone could get in them and they were flattering. There was a simplicity to Rudi’s clothes. You might see a simply cut dress in one of his shows that had a very flamboyant pattern and then all these accessories to dramatize the whole thing to make it newsworthy, but you take that same dress and cut it in navy wool tweed and anybody could wear it and they did. Those were the clothes that people were coming for. You should not get the idea women were wearing these far out very dramatic pieces. [Broadway legend] Carol Channing would, because she had that kind of personality. She was one of the most professional people I had ever worked with in that kind of environment, where all she is doing is getting in and out of clothes. There was no ego involved with her whatsoever. When she walked into a room, that was it, the whole place was on fire. But no ego. It was really interesting. I helped Barbra Streisand one evening, 1966, 1967, when she came in to buy some personal wardrobe. She went through the collection and she put together a group of clothes that was completely interchangeable. Most fashionista people are not terribly bright in my opinion, but I thought, ‘My God, this woman has really got a brain.’ Sharon Tate and her sister, who was also absolutely gorgeous, used to come in and buy. I would very often be the one who was assisting and writing

up the order. But not all of the clientele would come into the showroom to buy clothes. [Indian politician and prime minister] Indira Gandhi bought directly from Rudi, while Jackie Kennedy was going to Saks.

Elizabeth Saltzman: I wore it all the time when I became capable of wearing it. It wasn’t about sensuality or being extreme, because I wasn’t aware of what they were. It was about feeling different and cool, without trying. It was my norm, it was what you borrowed from your mother’s closet. Rudi’s clothes weren’t something architectural in the sense of construction; they were clothes that didn’t fight your body. They were retro, but in no way had they dated. I still don’t think there is a date to them – they are classics.

Marylou Luther: Rudi was a sociologist, anthropologist, humanist, psychologist, psychiatrist, revolutionary, innovator, fortune teller, dancer, comfort seeker, artist, artisan, and on and on and on. And he liked to shock. Baring breasts and pubic hair, passing out guns at his show, shaving bodies and heads, dressing models as nuns – he called them the Sisters of the Immaculate Mascara – these were not acts of maintaining the status quo.

Barbara Bain: Rudi was an exceedingly intelligent man, and we had wonderful conversations whenever we met. It was just a comfortable exploration of the universe. It was good to be in each other’s presence. He was an artist, he was a visionary, he was a philosopher, he was so clever with his view of anything. I never felt like that about anyone else in fashion. Charles James was an artist, too, but he was such a miserable person. Everyone felt that, it wasn’t just me.

Léon Bing: He and I once went to San Francisco to do some television thing and I’m from the Bay Area so after, we went for dinner at Ernie’s, which was the place at the time. I ordered tripe and I ate it with such relish that the captain gave me another helping. One weekend, Rudi called me up and said, ‘You have to come for dinner.’ And I was not sure, and he said, ‘You have to!’ Now, making tripe involves cooking it all day and throwing off the water and adding new water and it stinks like a charnel house while it’s cooking. And when I got to the house, Rudi had spent the whole day making tripe. He knew I loved it and that’s what he’d done for me. That was the kind of guy he was.

‘Rudi liked to shock. Baring breasts and pubic hair, passing out guns at his show, dressing models as nuns – these were not acts of maintaining the status quo.’

Layne Nielson: Rudi was so entwined with California, that was part of his identity, but he spent a lot of time on the East Coast. All of our major shows were in New York. They were very small and it is hard to imagine anybody having a show that would make a nationwide impact in such a small and unpretentious space. I think Rudi’s showroom was 530 Seventh Avenue. It was small, with folding chairs. There was no hoopla, no music. Rudi might have only 30 pieces, because he was a lazy designer and didn’t produce many clothes, but even if it was not a huge collection, it was loaded with drama. The explosive way he would put colours together shocked everyone in New York in the 1950s. I did all the accessories from the head down; the shoes were Capezio. Rudi found one style that he stuck

with. It was called the Gondola, like a little French pump. We had the same shoes for every show. It was the perfect style for any Rudi Gernreich clothes because it only had a two-inch heel. You couldn’t show Gernreich clothes with a spike heel. Occasionally when Rudi would go off on some wild creative bent, Capezio would make something special like boots, but always with a low heel. Rudi would stand right out in front of the dressing room and narrate from beginning to end. He was the star of the show. He had a very sophisticated, educated voice, though he didn’t have an education. In his early years, he still had a German accent, but he wanted to become an American and how he managed to be able to speak such perfect American English, I don’t know. Not a hint of an accent. And his grasp of the language was so thorough that he could make puns on any subject that were just spot on and hilarious.

Marylou Luther: Rudi’s biggest mistake was not having a business partner to help sell his clothes to major retailers. And not showing in Paris. Without Paris as a stage, with all its publicity and attendant fashion power, he really never attained the fashion status he deserved.

Issey Miyake: Rudi Gernreich was the designer I admired the most, back then. But then there were many other designers who also admired Rudi – I believe Claude Montana did, too. I first met Rudi in New York and I remember visiting his studio in LA. Later, he came to Japan to attend the Osaka Expo ’70 and attended one of my first fashion shows. He was intrigued by the school uniforms worn by Japanese kindergarten children and created a grown-up version. He had a wonderful sense of humour. He loved to create the reverse of ideas in that way. What I remember the most about Rudi is of course the photo of the two naked people, one male and one female, with shaved heads. The models were Renée Holt and Tom Broome. It was beautiful. It was way ahead of its time and the work of a pioneer. He was very courageous. Tom Broome later worked in my studio in Tokyo for a few years.

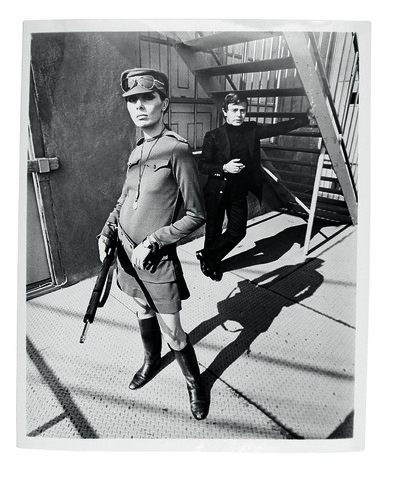

Barbara Bain: I went off to the UK in the 1970s to do this TV show called Space: 1999. The producers Gerry and Sylvia Anderson came to meet with us and tell us what the series was going to be like, and Sylvia said, ‘The only American designer I would be the least bit interested in designing the costumes for this would be Rudi Gernreich.’ And I said, ‘OK, well, I can call Rudi.’ He was semi-retired by then and he had pulled back. He was thinking a lot. But he did those costumes for us with colour-coordinated sleeves, with the colour to indicate which department you were in on the space ship. When I met with Rudi and we spoke about it, he said quite a startling thing. I asked him, ‘What do you think we’ll be wearing in 1999?’ ‘Well, I am worried,’ he answered. ‘Armour.’ That word never left my mind.

Michèle Lamy: I opened my store on Santa Monica Boulevard in 1979. His studio was not that far away and I became part of Rudi’s afternoon promenade or something. He started coming to the store to hang out. He was always in black. He told me so many anecdotes. We talked about the world and why he had been abandoned by the press. I had the feeling that he was so disappointed with life at that time. He wanted to see something new, or what we were doing. He never came in with his own pieces, but he had a lot of his communications.

Rick Owens: You mean he was bringing his clippings? It was more important to prove his relevance to you rather than to talk about the clothes themselves?

Tim Blanks: Was he quite bitter?

Michèle: I wouldn’t say bitter, but sad. Extremely sad at that time. He was not so attractive, where he had been so attractive before. He was hanging out on the boulevard to pick up some beautiful boy.

‘Rudi’s big mistake was not showing in Paris. Without Paris as a stage, with all its publicity and power, he never attained the status he deserved.’

Tim: Really? But he had Oreste waiting at home.

Michèle: He was very nostalgic, wanting to be somebody else.

Rick: When he came in, were you like, ‘Oh, a legend’ or ‘Oh, a loser’?

Michèle: Neither. There were a lot of characters, you know, who were extreme. It just seemed to be the normal thing that he was there. He was very supportive of what I was trying to do, but on the other hand, he did not think he had the energy to do something. That was the end for him. It was very sad. He didn’t have too many friends, and he was more hanging out with us to look at what we were doing, because we were something new and fabulous in LA, and we were leaving him a bit behind. And he was very aware of that.

Rick: When you say ‘we’, you mean, your friends, your clients or your boyfriend? Who is ‘we’?

Michèle: All of the above. You know in the store you had all these people there, so you had a little court.

Rick: He was just into hanging out with this little nest of cool kids?

Michèle: Yeah. And at the time, Maxfield was still on Santa Monica at the end, on the corner of Doheny. Tommy Perse was selling Giorgio Armani there, and I had plastic shoes, like Oxfords, in all the colours. So Tommy was bringing people to hang out, too, but he was telling people in straight suits, ‘You should wear summer shoes.’ He was giving other people a hand at the time, a lot. So that was on the boulevard, at the beginning of Boystown. And my first day coming in from the airport, I thought this block looked good. Tony Duquette was in one of the studios behind.

Rick: Tony Duquette and Rudi Gernreich on the same block!

Tim: Did you know Rudi left his entire estate to the ACLU?

Michèle: I remember him talking about that, and how he was going to leave everything to that society, yes.

Tim: That was quite a groundbreaking gesture. Was he sad because he’d been forgotten?

Rick: Forgotten? Or that he had been overlooked? That he had never gotten enough respect? I mean he got respect, but he felt like it was over.

Michèle: He felt it was over. He did not make money out of it. Rudi was thinking that William Claxton was against him and thought it should be about Peggy

and not Rudi.

Rick: He and William Claxton clashed over who should have been responsible for his fame.

Tim: Did you like Peggy?

Michèle: Of course, I liked Peggy. I liked to see her, there was not so much to talk about. I didn’t have a relation with Peggy and Rudi together. I understood that it was a competition with Peggy thinking she did those clothes, but they looked very fabulous on her. There was also Vidal Sassoon in the story because her look started with the cut from Vidal, and he was huge. They were all huge at that time.

Rick: Real fashion freaks like us love having an obscure kind of exotic designer as a private icon.

Michèle: That was not what he wanted. Out on the sidewalk.

Rick: It’s not like he was broke. What was he expecting, to stay famous forever? He left behind beautiful images and a lot of them.

Michèle: But at that time, there was a Fiorucci opening, and the whole world was coming. I remember thinking that Fiorucci was something that Rudi should have been part of and was not. No one was taking care of him. I also think that what he did, the jersey, the monokini, his liberation of the body really became a sport thing. It was Jane Fonda who really continued it, but everything was made into spandex.

Rick: That’s true. If he had gotten into active wear…

Michèle: That is what I thought, that should have been the follow up. But it came just 10 years too late for Rudi. The timing was wrong. Imagine Baywatch if they’d been wearing Rudi; it would have been incredible.

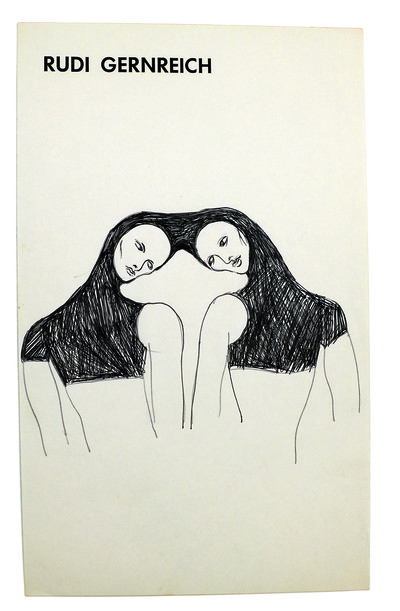

Cameron Silver: We have to realize the trifecta of Rudi, Peggy and Bill was quite magical and I don’t think there has ever been a fashion collaboration that had the same kind of impact. She was very protective – rightfully so – of Rudi because it defined so much of herself in popular culture. It’s so difficult for me to be objective and I am sure it’s difficult for Peggy to be objective. They were so close; they were like a psychic brother and sister in the way that they worked.

Layne Nielson: Throughout the 1960s when Peggy was pretending to be the most famous person in the world, she was loathed by everyone. It pains me to say that because I was good friends with her at one point.

‘That whole activewear explosion came 10 years too late for Rudi. Imagine Baywatch if they’d been wearing Rudi; it would have been incredible.’

From many accounts, that symbiotic relationship between Moffitt and Rudi soured towards the end of Gernreich’s life, with posthumous rumours of a struggle over photo archives and even the legal rights to the Rudi Gernreich brand name. In her 1998 Vanity Fair profile of Gernreich, writer Cathy Horyn reported that Moffitt and Claxton had acquired the trademark to Gernreich’s name, with a view to finding investors and reproducing Gernreich’s designs under a label that would include her name. When Horyn mentioned this to Oreste Pucciani, she wrote that, ‘he replied by saying something in French that roughly means “Up yours” and calling an attorney.’

Layne Nielson: It was terrible at the end, Rudi was so heavily drugged. He was struggling with English, even though his English was much better than mine. Before he went on the drugs, I took him to the hospital one day and he was announcing to people in the hallway that he had cancer. It seemed like it was something that hit him that he just could not quite believe it. So he never expressed anything about his life to me, regrets or anything. Some years before, he did say something to someone about how he wished he hadn’t done some of those outrageous things at the very end, like the show that brought him down, the impossible, overdone Turkish things. But he wasn’t at all spiritual. There was no religion whatsoever anywhere. He was an atheist; we were all atheists.

Marylou Luther: The last time I saw Rudi, he was in the hospice. It was new. He was their first patient. Ever the pioneer. He was lucid.

Layne Nielson: The last time I saw Rudi was the night before he died. For many years when he was doing all kinds of other things, he would call me in to make a presentation for something. My sort of expertise, if I had any, was in graphic design, so I would give him that if he needed it. As the years when on, we both went off into other things. Near the end of his life, when I heard he was ill, I wrote him a note wishing him the best and he called and he said come up. This was probably in January or February 1985. Rudi had been diagnosed with cancer, and he said, ‘I am writing my childhood memories in German and I want you to help me with the translation into English. I want to publish them in your hand-printing on lined paper schoolbooks.’ I have the original German in his handwriting, and the English in mine, not writing but printing. It really touched me that he admired mine. That was how he wanted his stories to appear. So, for maybe two or three months, that is what I did. I was there every afternoon, going through these childhood things. That was probably when I first had a glimpse there was more to the man than I had ever known. We got through quite a few of them, but then he was taken into the hospice. I was sitting with him. One of his cousins had come from New York and we traded off sitting spells so he would never be left alone. I was with him the night before he died.

All the clothes that were left in Rudi’s hands went to the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in Los Angeles. The collection was offered to LACMA as an outright gift and it was turned down by this twit who was there at the time. I think his excuse was that ‘it was too much of one designer’! LACMA also had all of the patterns that came from Walter Bass, and they were put in a dumpster. Someone on the staff called up Bella Lewitzky, a dance friend of Rudi’s and she went to the dumpster with a truck and pulled all of them out to save them. They are now at UCLA Special Collections.

Rudi and his partner Oreste Pucciani bequeathed their estates to the American Civil Liberties Union, creating a living legacy, and a permanent reminder of their activism in life. The following statement comes from the ACLU:

The gift from Rudi Gernreich and Oreste Pucciani to create the Gernreich-Pucciani Endowment Fund for LGBT issues is utilized to support our LGBTQ work generally, both in Southern California and nationwide. The funds have not supported one specific case or campaign, but rather have helped make possible many important victories including:

•The ACLU and our allies won a historic U.S. Supreme Court case in 1996, Romer v. Evans, establishing that gay people have the same right as other groups to seek government protection from discrimination.

• In 1997, the ACLU brought the lawsuit that triggered the first state policy authorizing joint adoption by gay couples, and in 2010, the case that ended the last state law explicitly banning adoption by gay people.

• In 2008, the ACLU won a milestone for transgender rights on behalf of Special Forces veteran Diane Schroer, whose U.S. government job offer was rescinded when officials learned that she was transgender.

• In May 2014, we won a groundbreaking ruling striking down Medicare’s 30-year blanket ban on coverage of gender transition-related surgery.

• In June 2015, the ACLU won the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges affirming same-sex couples’ constitutional right to marry.

• In 2018, we helped Anchorage become the first U.S. jurisdiction to vote to uphold transgender protections on a stand-alone measure.

‘The last time I saw Rudi, he was in the hospice.It was a brand-new place. He was their first patient.Ever the pioneer. He was lucid.’

On May 9, 2019, the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles opens an exhibition called

Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich.

Bethany Montagano, curator: At the Skirball, where we are guided by the Jewish tradition of welcoming the stranger, we are inspired by how Gernreich did just that: his apparel welcomed everyone into the fold – regardless of race, religion, gender, sexuality, and body type – broadening the scope of who is ‘fashionable’. We hope that visitors are inspired by Gernreich’s fearless fashions and his lifelong credo that style is about freedom and authenticity.

Humberto Leon, co-designer at Kenzo and co-owner of Opening Ceremony: I’ve consulted on the exhibition at the Skirball from the beginning. I’m not entirely sure why they wanted me. I am an American designer, I am gay, I do a lot of social justice work, so they tell me I compare well. There are lots of things Rudi did that I look up to. I feel like he was an extremist in his time. There’s the fact that he was an American but in a weird way, always pushing the boundaries. He was commercially savvy and did amazing stuff that women wanted, but it was a particular person who wanted a miniskirt when miniskirts weren’t popular, or who was interested in exposing her boobs when that wasn’t popular. I don’t think he was anywhere near what commercial means in today’s world, but he was definitely doing things that an alternative and younger community was really excited about. He was doing things that were revolutionary – the patterns, the cut-outs. The flat shoes were a good example. He was really all about women being comfortable, almost barefooted, and if you think about the time period he was working in, that is so interesting. He was also surrounded by a ton of artists. He was really carving his voice in terms of art, fashion and politics. When a designer nails all those points, it’s just super exciting. The same way maybe Mugler did it in the 1980s. Gernreich was as big and as revolutionary as that in his time period.

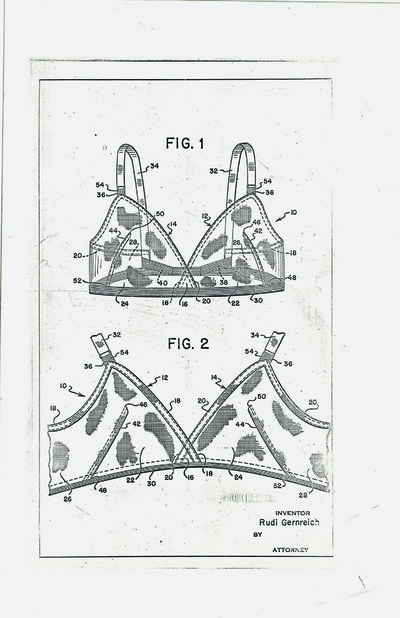

Marylou Luther: Was Rudi ahead of his time? Was Longfellow a poet? Was Shakespeare a writer? If he launched now, I think Rudi Gernreich would be the fashion superhero of the moment. I see his influence in graphics. His black-and-white geometrics – circles, stripes, triangles, squares, plaids – and the way he combined them are an obvious influence on today’s fashion prints and patterns. I also see his influence in body-slashing, body-baring, body-peeping through fabric arrangement and disarrangement. And in his lunar expeditions. Another major Gernreich contribution to fashion was the ‘no-bra’ bra. It probably did more to change the way clothes fit than any other single item of apparel, intimate or not. And compared with the twin torpedo brassieres of those days, which Gernreich compared to ‘something you put on your head on New Year’s Eve’, the ‘no-bra’ bra for Exquisite Form was indeed revolutionary, freeing women of the padding, boning and topstitching that characterized bras of that era.

Tom Ford, designer: Rudi is certainly deserving of a better place than he has in fashion. But American designers don’t have that place in fashion. The credit always goes to the Europeans, particularly the French designers working in that period. American fashion wasn’t global then, which is something I’ve said about my new role at the CFDA. I want to bring America a bit more out of its shell. America is a very introspective country, maybe the most isolated in the world in terms of understanding that there is a world out there. That’s why most American fashion designers never make a success globally like the European brands. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that America is so inward-looking.

‘Was Rudi ahead of his time? Was Longfellow a poet? Was Shakespeare a writer? If he launched today, he’d be the fashion superhero of the moment.’

Humberto Leon: I was excited about this exhibition because a lot of Rudi shows in the past have ended up being about Peggy Moffitt. Obviously, she’s instrumental as a muse, but this time, the focus was really on Rudi, as an immigrant moving to America, finding a community and a voice, and how this guy in LA changed what women could wear through the ages. And, yes, he doesn’t get the credit. He is not a part of the general conversation due to the fact he was living in a place that was really about Hollywood gowns, and there are so few designers that actually make it big out of California. That’s why this exhibition is so important. It talks about the innovation and the politics. The Skirball is very big on social justice. It is really focusing on that more than it just being about fashion, and talking

about the revolutionary aspect. It brings Rudi back into the conversation. And it’s more relevant than ever, with the issues around immigration. He is the quintessential outsider who really made himself who he wanted to be. And that is such a profound statement for emigrants today. So someone like Rudi can stand the test of time. I’ve been meeting with people on the East Coast and in Europe to see how the show could travel.

Layne Nielson: Rudi said, ‘My aim is to liberate’ – and he did. There are only a handful of real milestones where you can say, ‘This had an effect on changing everything that came after it.’ At some point, Rudi reached the point where there were fewer and fewer of those opportunities. He was continuing to deconstruct and to cut away at clothes and if you start down that road, you know where it leads – to total nudity. And once you get there, then what do you do? Do you backtrack? If you are an avant-garde futurist, it doesn’t work. Rudi’s last collection was like everything and the kitchen sink, all this stuff piled on, you could barely see the model’s nose and mouth. That was the end. But go back to the beginning. There was a knit sheath dress that Marilyn Monroe wore in 1954, no construction, no nothing, just a tube, and it revolutionized the entire industry. Swimsuits were never the same after Rudi came out with the five-button knit maillot.

That was another revolution. Then the next one was the entire brassiere industry which he changed completely, after his topless swimsuit and the ‘no-bra’ bra. Those are the big legacy items. And he certainly is responsible for the thong, which nobody knows, though I don’t think that is revolutionary in the same way as those other three items.

Cameron Silver: [My vintage-clothing store] Decades opened in 1997 and I can remember early on, getting a very large Gernreich collection and having a mini

retrospective within the store. With vintage fashion, I always tell women of a certain age that when they have a large collection of a certain designer, they create the moment. I think if I were to get 40 or 50 pieces of Rudi Gernreich in the store, it would stimulate an appetite. But it is really dependent on those collections coming in, and we haven’t had a lot of Rudi come in recently. The challenge with Rudi today is that the Harmon Knitwear is heavy for a lot of women. It may limit how much we see it on people because of the weight of the fabrics. And the survival of them is difficult because of moth damage. But the silhouettes are so brilliant that when

we get one in good shape, they do sell. The pieces that I am most attracted to tend to be the jersey knits with the cut-out pieces, I think they are spectacular. Fashion designers love Rudi.

Tom Ford: I’ve often looked back at Rudi’s work for inspiration. When I did A Single Man, I dressed Julianne Moore in a black-and-white dress because at that time the idea of having something so graphic would have been very advanced. It wasn’t Rudi Gernreich, but this character would have been ahead of the curve, would have known who he was, would have been influenced and inspired by him. Rudi was the fashion equivalent of Andy Warhol in pop. Very bold, simple, doing very advanced things for America at that time, when so much fashion was coming out of Europe. There was a cleanliness to his work, and that to me is the part

that is very American. And of course, he sexually pushed a lot of the boundaries, which I’ve always loved, with the bare midriffs, the monokini and the cut-out pieces covering the breasts.

‘Rudi was the fashion equivalent of Andy Warhol. Bold, simple, doing advanced things for America, at a time when so much fashion was from Europe.’

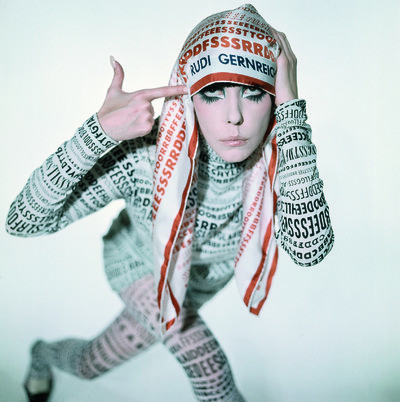

Marc Jacobs, designer: Anna Sui and I know Rudi Gernreich because we love fashion. Rudi was someone who thought outside the box and created these fantastic fashion illustrations and these concepts. Commerce never seemed like the motivation for what he did. He was aesthetically driven. I think he had something to say aesthetically and what he said still feels effective, with its graphic quality. If I singled out certain things – the topless bathing suit wasn’t my thing – but those incredible T-shirt dresses on his muse Peggy Moffitt. Also, their working together and influencing each other created these fashion moments that still resonate with me. They were almost more Martha Graham-y. I don’t know what the first thing I saw was – maybe the T-shirt dress with the stripes – but when I saw an image of Peggy Moffitt with her makeup in a creation by this man named Rudi Gernreich, I could immediately write his story or imagine his history. It gave me all of that in one image with no explanation. How much more seductive could anything be than, ‘Oh my God, that gives me this! And this! And this!’ I would compare him to people who came later like Stephen Burrows and Courrèges, even if Courrèges was still in the couture language, and there was none of the stuffiness or the structure or the architecture of couture in Rudi. There was just this great appreciation for the body.

Pierre Cardin, designer: I met Rudi during my first trip to New York and we instantly bonded. He invited me to his home in Los Angeles and we remained lifelong friends. I often travelled with him around the US, notably to Las Vegas and along the West Coast. He was a talented and audacious man – a real designer. I truly respected his work, and loved his taste for experimentation and provocation. He pushed things forward and shattered taboos. We were the same age and he died too young. It’s such a shame that today he seems to have been slightly forgotten.

Cameron Silver: I think what he did for fashion is quite similar to what Chanel did. I always think the three great designers who revolutionized women’s fashion in a forward-thinking way were Chanel, Gernreich and Halston. Rudi and Halston both had that love of dance. The difference is that Halston started as a milliner. But there is that great Rudi look – the four-sleeved sweater, with two of the sleeves tied casually over the shoulders – which is a total take on Halston. I think they

were playing off each other a little bit. They were the master modernists. The other side of a great designer is that you can look at the work from afar and know what it is, and Gernreich was one of those designers. You can see a certain pattern or a silhouette and be like, ‘Oh, that’s Rudi.’

Layne Nielson: Rudi would make fun of Halston, but Halston could not have existed without Rudi because what Halston was doing was just more Rudi. At that time, Rudi was doing some very, very simple things and that is all Halston did. I have some photographs of Halston things that appear to be direct knock-offs, but nobody picked up on that.

Elizabeth Saltzman: Halston was so out there and so revered and he was influenced heavily by Rudi. If you look at it, Halston took someone who didn’t have the publicity machine to be a social power – and Halston did. There are maybe hundreds of designers who haven’t made it because they didn’t have social capabilities. Rudi isn’t someone who gets brought back, and I guarantee you he’s not studied. He should be, though. He should be part of every fashion person’s education as much as any old Hollywood film star is. With all the health, wellness and fitness in the fashion world, it would be cool to do a Rudi Gernreich Award for Sportswear.

Tom Ford: Halston was more sensual, whereas Rudi Gernreich was not necessarily sensual. The bits and pieces of the body that were exposed were less sensual and more graphic, though maybe that was just Peggy Moffitt. The fabrics Halston used were slicker and drapier whereas Rudi’s fabrics were stiffer and held shapes. A lot of them stood away from the body. He was more early 1960s and Halston is obviously more 1970s, but graphically, yes, he would have been very inspirational. Though I think it would have been a kind of inspiration by osmosis having grown up in America in the 1960s. Rudi was kind of an American version of what Courrèges and Pierre Cardin were doing. I’m not saying he was the only person who was creating these very simple graphic futuristic shapes but for an American designer – and a West Coast American designer, which I also love about him, of course – he was very influential. And he was way ahead of the curve with the androgyny. Even with some of his menswear, it was very much like what Pierre Cardin did with menswear. It’s very hard to know who thought of what first and what was in the air, especially when you have all these people overlapping at the same time. Who really did invent the miniskirt? Mary Quant thinks she did, but

then you’ve got other people doing it at the same time. And graphically, I’m looking at things that were quite Ellsworth Kelly. Bridget Riley, too.

‘Gernreich wasn’t a one-hit wonder. He was the birth of modern fashion, and he also created an incredibly liberating moment for women.’

Irving Blum: If I had to think of an analogy in the art world for what Rudi was doing, it would probably be Bruce Nauman, in terms of work that was controversial and quite different from anything around. What Rudi was up to I always thought was really important. He was hard to categorize. How do you fit him in? Well, the answer is you don’t. He was completely his own man, and I think people still have rather a hard time dealing with him. It’s to do with his radicality. That’s why he’s not so well-known now. But I think people will come back to him. There’ll be a time when Rudi makes sense to the world. I don’t know when or why, but I am of a

mind that it will certainly happen.

Cameron Silver: He was the antithesis of a one-hit wonder. He created some of the most important examples of 20th-century fashion. I like to think of it as the birth of modern fashion, but also it was an incredibly liberating moment for women.

Léon Bing: After Rudi died, I had so many clothes because I used to take samples home in lieu of payment. Most of them went to the Met. It was marvellous being his model. When they were in LA, people like Baron Niki de Gunzberg would come to the studio and I would show them the collection. And the photographer George Hoyningen-Huene. He was very old when he came, but he took a wonderful portrait of Rudi that we have on our wall to this day. Rudi will never die to me.