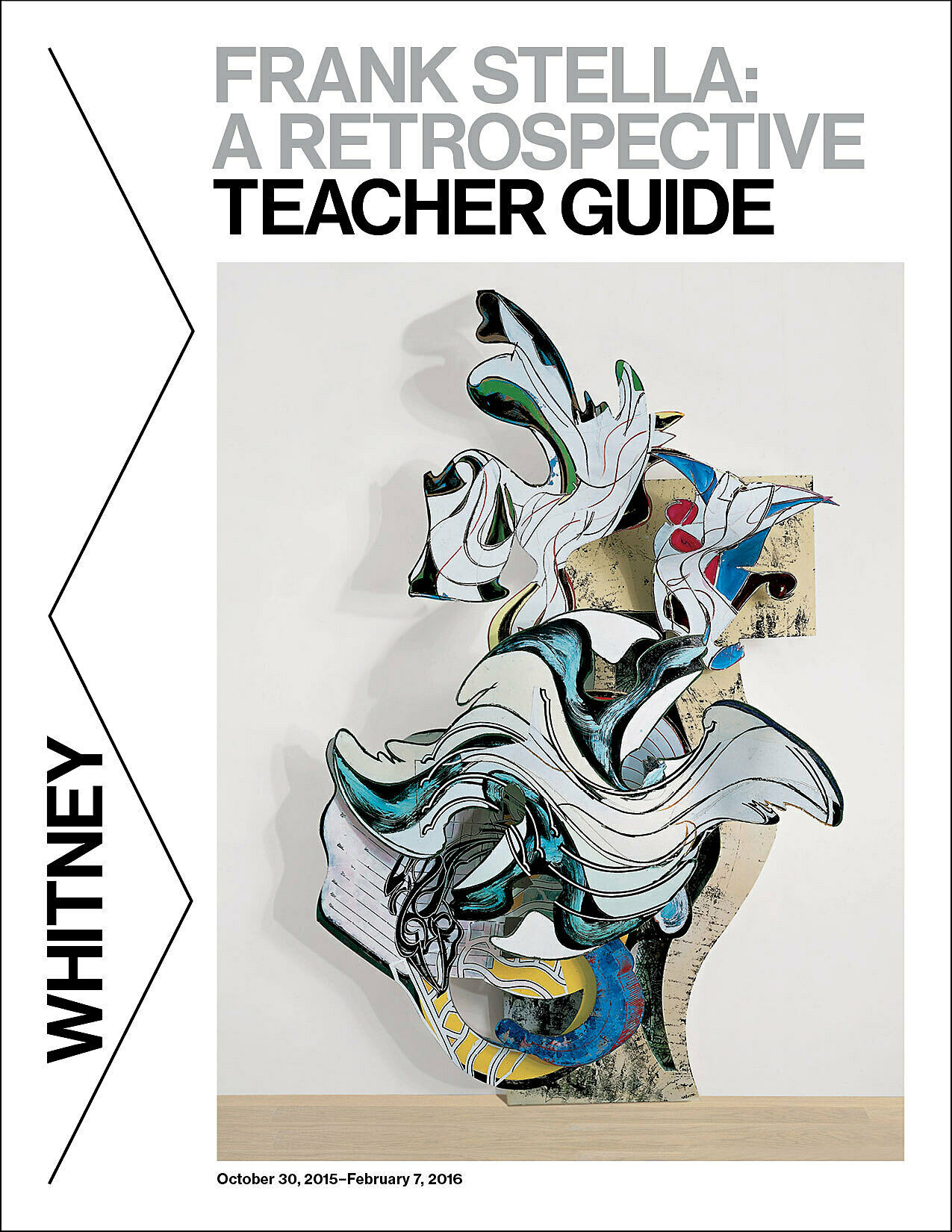

Teacher Guide:

Frank Stella: A Retrospective

Oct 30, 2015

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Frank Stella: A Retrospective, on view at the Whitney from October 30, 2015 through February 7, 2016. The exhibition features paintings, reliefs, sculpture, and prints that span the artist’s career. Also on view are drawings and maquettes that exemplify Stella’s conceptual and material process.

For almost six decades, Stella has explored the materials and processes of painting. From his earliest paintings completed when he was in his twenties to his recent large-scale work, Stella has continually re-invented and pushed the limits of abstraction. He asks us to consider what an abstract painting can be. Can it tell a story, sound like music, or is it just lines, shapes and colors? Or perhaps an abstract painting is just the materials it is made of, as Stella simply said, “What you see is what you see.”

Read an article about Frank Stella and his work in The New York Times:

When you and your students visit the exhibition, you will see a selection of works by Stella that reveal how he has explored and experimented with abstract painting. This guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offers suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts. These materials have been written for Elementary, Middle, or High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team at the Whitney

FRANK STELLA: A RETROSPECTIVE

The more paintings you make, the more you learn.”

—Frank Stella

By any measure, Frank Stella has learned—and taught us—a great deal about abstract painting. For almost six decades he has worked with unparalleled intensity, producing several thousand paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures. The exhibition—which inevitably presents only a selection of Stella’s vast output—is the artist’s first retrospective in the United States in almost thirty years. Although its thrust is chronological, the artist, who was deeply involved in its installation, made a number of strategic interventions into the exhibition’s temporal thread to reveal the range of his visual concerns as well as continuities in seemingly disparate works. Some rooms function as medleys, drawing out relationships among works executed across the years—suggesting that even the most minimalist compositions are not devoid of meaning but invite associations with architecture, landscapes, and literature.

Born in Malden, Massachusetts in 1936, Stella’s first experience with paint was painting houses and boats with his father in his youth. He began making art seriously in the early 1950s while attending Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. Between 1954 and 1958 Stella studied painting and history at Princeton University, where he first produced paintings in an Abstract Expressionist style, employing loose brushwork and abstract forms. When he moved to New York’s Lower East Side in 1958, Stella’s compositions grew clearer and more defined as he addressed the problem of how to make a painting. In his exploration of abstraction, Stella worked in series, developing increasingly complex variations on selected themes.

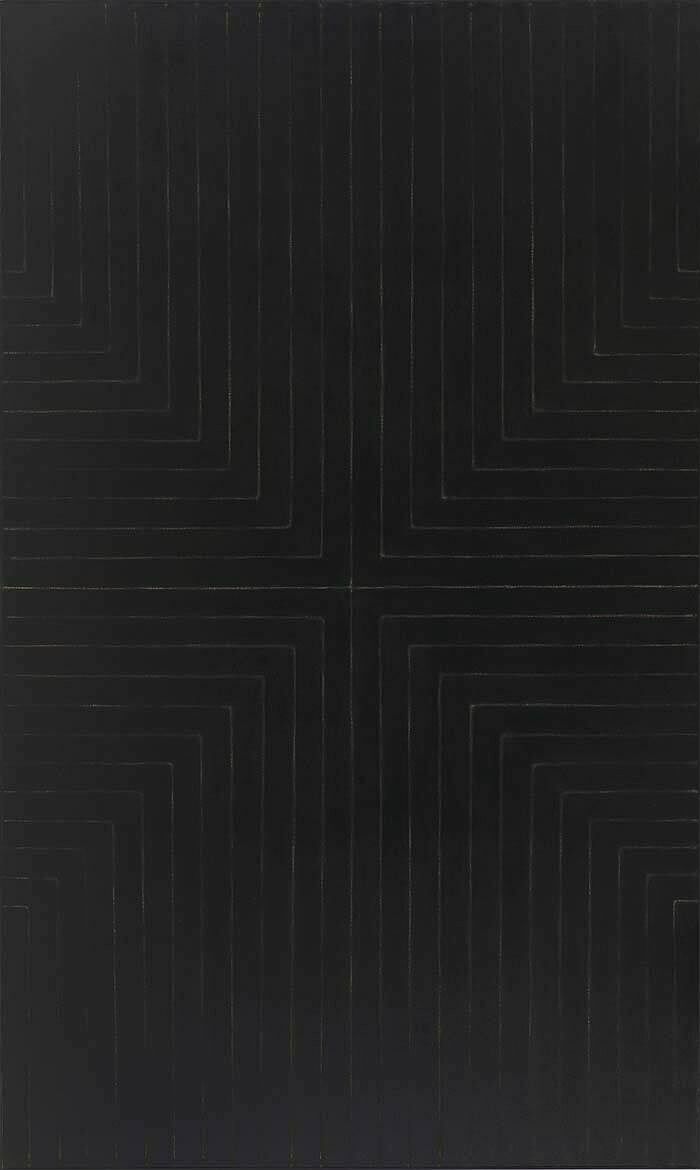

By 1959, Stella was making symmetrical, linear compositions that systematically alternated bands of black enamel house paint with lines of exposed canvas, creating a unified, forceful, and immediate visual impact and object-like quality. The result was his first series of radical abstractions, the Black Paintings, (1958-60). The Black Paintings, in their simplicity and use of a single color, opened new paths for abstraction and exerted a profound influence on the art of the 1960s.

In the following decade, Stella began producing shaped canvases that opened up new possibilities for what “pictorial structure could be.” Rather than serving as neutral supports, the canvas and stretcher bars instead became essential parts of the image. By the mid-1960s he was producing bright, multi-colored, and even more eccentrically shaped paintings with rigidly crisp, geometric forms.

In the late 1960s, Stella began gradually but methodically to incorporate increasingly different kinds of elements into his painting—color, material, and space—as if to see just how far he could push abstraction. His Protractor Paintings (1967-71) built upon these explorations in color and shape. The use of curvilinear elements, which have often been compared to patterns traditionally found in Islamic art, added compositional and linear complexity to his work. During the 1970s, Stella opened up the medium of painting as radically as he had once reduced it, making curvilinear, improvisational, highly painterly works which he executed on massive aluminum armatures.

Stella’s fearless attitude toward change and constant willingness to set himself new problems and explore new forms, materials, and techniques has meant that his art has always responded actively to its time. Over the last thirty-five years, much of Stella’s work has been related in spirit to literature and music. In recent decades he has made strategic use of advanced technologies such as 3-D printing, and computer-aided design (CAD) software has been essential in his visualization and fabrication of complex sculptural forms. Stella’s recent work testifies to his flexible, innovative approach to the aesthetic problems he sets for himself as well as his ability to constantly reinvent himself.

Works cited

Auping, Michael. Frank Stella: A Retrospective. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2015.

Stella, Frank. Working Space, (The Charles Elliot Norton Lectures), Harvard University Press, 1986, 60.

Frank Stella, Die Fahne hoch!, 1959. Enamel on canvas, 121 5/8 x 72 13/16 in. (308.9 x 184.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz and purchase with funds from the John I. H. Baur Purchase Fund, the Charles and Anita Blatt Fund, Peter M. Brant, B. H. Friedman, the Gilman Foundation, Inc., Susan Morse Hilles, The Lauder Foundation, Frances and Sydney Lewis, the Albert A. List Fund, Philip Morris Incorporated, Sandra Payson, Mr. and Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Percy Uris, Warner Communications Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts 75.22. © 2015 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © Whitney Museum

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one or two works of art in the exhibition. See the Images and Related Information section of this guide for examples of works that may have particular relevance to your classroom.

Objectives:

- Introduce students to the work of Frank Stella.

- Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit.

- -Explore some of the ways that Stella learned about painting.

Artist as Experimenter

WHAT IS A PAINTING?

“There are two problems in painting. One is to find out what painting is and the other is to find out how to make a painting.“

-Frank Stella, Pratt Lecture, presented at Pratt Institute, New York, Winter 1960.

Early in his artistic career, Frank Stella learned about painting by questioning what it is. Ask your students to discuss what constitutes their idea of a painting and what a painting can be about. Consider what materials and tools it is made with, what the support can be (for example, canvas, paper, wall, wood, metal, glass), who makes the painting, and how it is viewed.

a. You may want to ask younger students to imagine what they could paint with instead of brushes. For example, fingers, hands, or sponges.

b. Ask students to think about what makes a painting different from other types of art, such as a drawing or a sculpture.

c. If your class has recently done an art project or seen an exhibition at a gallery or an art museum, ask them to consider how the work that they made or looked at together as a class matches their definition of a painting.

Artist as Experimenter

ABSTRACT SURROUNDINGS

“Learning how to make abstract paintings is just about learning how to paint, literally learning what paint and canvas can do.”

-Frank Stella

While learning how to make abstract paintings, Stella adopted a systematic, problem-solving approach. East Broadway (1958) takes its title from the main thoroughfare of New York’s Chinatown, which was just a few blocks from Stella’s first loft on Eldridge Street. Upon moving to New York City in 1958, Stella painted houses part-time—and he used the same commercial paints in his art. He bought unfashionable colors from the bargain bin, used a house-painter’s brush, and stretched his canvas on frames he built from 1X3" boards. Stella titled some of this series of paintings after places in New York City, noting that their geometric structure reminded him of the semi-industrial, downtown cityscape that surrounded him at that time.

a. Ask your students to view and discuss East Broadway, 1958. Do the shapes or patterns in this painting remind them of anything? Have them imagine that the image extends beyond the limits of the painting’s edges. What else might they see in the surrounding space? Ask your students to discuss or draw what they might see.

b. Ask students to use two or three colors and two or three shapes to create an abstract work based on their surroundings—for example, a part of their school, city, or town.

Post-visit Activities

Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artist’s ideas through discussion and art-making activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? How did the exhibition change their ideas about what a painting can be? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Artist as Experimenter

SHAPE THE COMPOSITION

Ask your students to review and discuss Harran II, 1967. What mood does this painting evoke?

a. With your students, discuss how they could create other rhythms or sensations with these shapes. For example: what shapes and colors would they use to create a composition that is: peaceful or energetic, relaxed or tense, balanced or unbalanced, wild or calm, geometric or organic, symmetrical or asymmetrical? Students could choose their own descriptive word.

b. Copy and give each student square and quarter circle templates. Ask students to first draw shapes within the squares and quarter circles, then cut out the shapes and make a collage by joining the square and quarter circle shapes together in a configuration of their own design that evokes the descriptive word they selected. Students may want to draw shapes that follow the contours of the squares or quarter circles.

c. Have students use glue sticks to adhere the shapes to another sheet of paper or cardstock. .When they’ve made their collages, ask students to color the shapes, using colors that again evoke the word they chose to evoke the rhythm or sensation of their composition.

d. Ask students to find a partner and describe each other’s compositions. Have them discuss what makes their composition convey peacefulness, energy, relaxation, tension, wildness, calmness, etc.

e. Share and discuss students’ compositions. Is there anything in common among the compositions that are peaceful? Energetic? Relaxed? Tense? If so, what?

Artist as Experimenter

PICTURE THE STORY

Ask your students to view The Grand Armada, 1987. Find Chapter 87 of Moby-Dick here: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2701/2701-h/2701-h.htm

Ask students to read the chapter aloud in class. How does Stella convey a sense of the whale hunt through line, shape, color, movement, and energy?

a. Ask students to create an abstract artwork based on a book you’ve read as a class or a book of their choice. Have them choose three key images from the book or a chapter in the book to use. Ask students to play with line, shape, color, pattern, overlapping, orientation, and scale to provide a sense of the narrative and the overall mood of the book.

b. Discuss students’ work with the class. What books did they choose? How did they convey a sense of the book?

Artist as Experimenter

SEE THE MUSIC

Ask your students to view K.81 Combo (K.37 and K.43) large size , 2009. Ask younger kids what the shapes, colors and forms might sound like—for example, sharp, smooth, quiet, or loud. Play the Scarlatti sonata for your students while looking at the image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibqjmrpHGi4

Do they see any connections between what they’re listening to and what they see in this work?

a. Play a selection of music for younger students or ask older students to play music clips of their choice. List at least five adjectives that describe the quality of your music. For example, loud, cheerful, serious, aggressive, soothing, whimsical, somber, repetitive.

b. Ask students to use colored construction paper or card stock to cut, tear, rip, fold, bend, twist, or crumple paper forms and tape or staple them together to make relief sculptures that convey a sense of the sounds, energy, rhythm, and pattern of the music. Have students attach their paper shapes to chipboard, cardboard, or other type of sturdy support. Play the music on repeat as students are making their works.

c. Ask students to share their completed works. Review their list of adjectives. Does their sculpture communicate a sense of the music and the adjectives they selected?

Images and Related Information

EAST BROADWAY, 1958

After he graduated from college and moved to New York’s Lower East Side in 1958, Stella made a series of paintings with simple rectangular shapes and stripes. He used house paint from the bargain bin and house painter’s brushes to apply it to the canvas. Stella said that he was “learning how to make abstract paintings. . .learning what paint and canvas can do.” Some of these works—such as East Broadway—are titled after places in New York City. In this painting, the field of stripes—painted freehand—is interrupted by a solid rectangle. Stella has associated the straight-edged geometries of his early abstractions with the cityscape that surrounded him, and noted that the gritty palette of works like East Broadway hints at the semi-industrial atmosphere of downtown New York at that time.

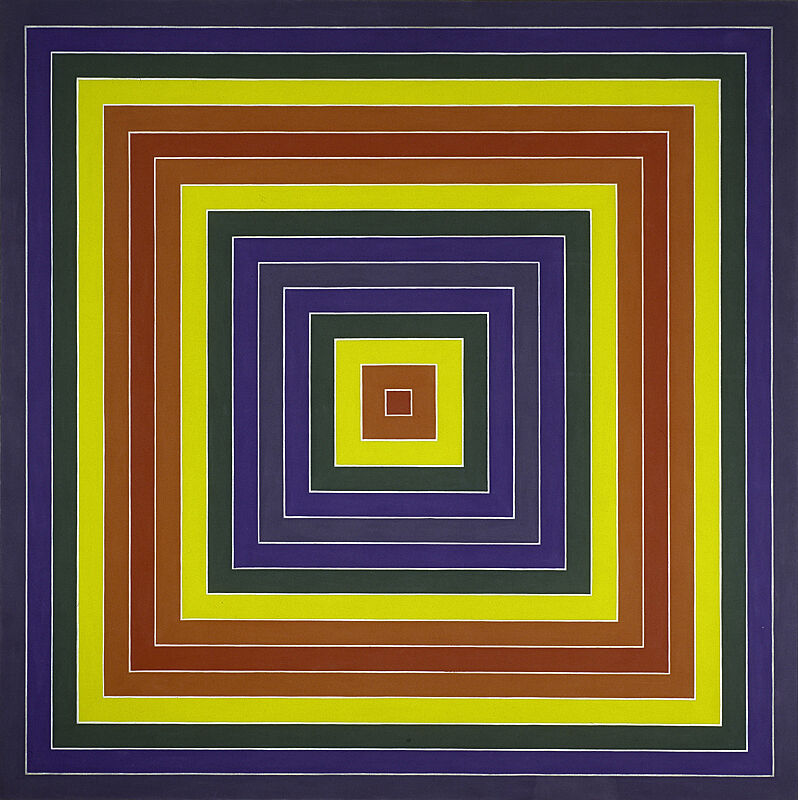

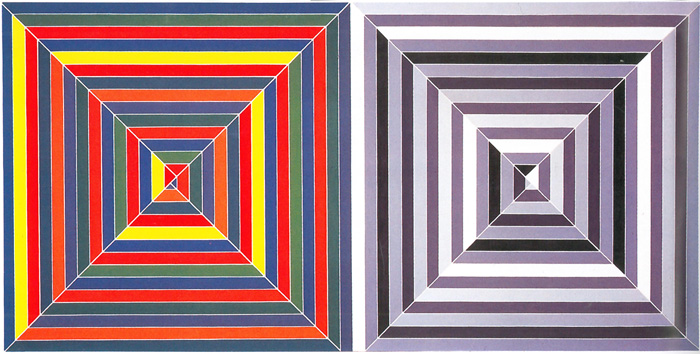

JASPER’S DILEMMA, 1962

At first, this painting recalls the kind of diagrams artists have used since the Renaissance to render perspectival space, with foreground objects appearing larger and those in the distance receding. Stella used primary and secondary colors, white, black, and various shades of gray to create this composition. He left a thin line of raw canvas between each band of color so that the squares and triangles that the bands make are visible. The squares are divided into four triangles whose points don’t quite meet in the center. The composition of stripes and the way that Stella combined the colors also form a central diamond shape and spirals that radiate from the center of each square. The title of this work and its color scheme refer to Jasper Johns; the “dilemma” makes explicit reference to Johns’s statement that the more he worked in color, the more he saw gray.

HARRAN II, 1967

In his Protractor Paintings (1967-71) Stella introduced curved shapes in bright and fluorescent colors and titled them after ancient cities with circular plans. The shapes of the paintings are based on the semi-circular protractor, a tool used for measuring and drawing angles and curves. Harran II is composed of eight-inch bands that arc like rainbows. The complex range of colors in this painting occasionally overlap and interrupt each other to punctuate its rhythm and add to its dynamism.

By intentionally merging abstraction with decorative forms and almost psychedelic color, Stella challenged the traditions of abstract and decorative painting and the long-held notion of the avant-garde that abstraction had to be difficult. Moreover, he was comfortable with making beauty part of the work and with the fact that some people might think his paintings were merely decorative.

THE GRAND ARMADA (IRS-6, 1X), 1989

Between 1986-97, Stella made hundreds of works inspired by Herman Melville’s book Moby-Dick (1851)—at least one for each of the novel’s 135 chapters. The series was initiated by an encounter with a beluga whale in an aquarium, after Stella was struck by the animal’s unlikely combination of mass and grace. While he did include fragments of recognizable imagery in the Moby-Dick works, the real aim was to respond to the relentless movement and energy of Melville’s language and story in more abstract terms, through the dynamic interaction of forms. This work is titled after Chapter 87 of the book which describes how the ship comes across a herd of whales in the Pacific Ocean and dispatches a fleet of boats to hunt them. In this chapter, the narrator Ishmael describes a vivid scene: as the men look into the water, a group of mother whales nursing their young beneath the boats seem to gaze back at them.

Read or listen to this chapter: http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/42/moby-dick/768/chapter-87-the-grand-armada/

K.81 COMBO (K.37 AND K.43) LARGE SIZE, 2009

Stella’s recent Scarlatti Sonata Kirkpatrick series (2006–ongoing), was inspired by the music of Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757), known for his harpsichord sonatas. The relationship of Stella’s multicolored steel constructions to Scarlatti’s music is one of visualizing sound rather than a literal correspondence. “If you were to be able to follow an edge” of a given work visually, says Stella, “and follow it through quickly, you’d get that sense of rhythm and movement that you get in music.” As Stella has pursued his central ambition—to make painting as vital and generous as it can be—he has increasingly moved the medium into three dimensions, the traditional realm of sculpture. Yet his concerns are primarily those of a painter rather than a sculptor. He has remarked: “A sculpture is just a painting cut out and stood up somewhere.” In contrast to sculpture’s hallmark characteristics of mass and volume, Stella’s use of steel and other metals in the Scarlatti series convey a sense of movement, flow, and visual play.

Bibliography and links

Auping, Michael. Frank Stella: A Retrospective. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2015.

Rubin, William S. Frank Stella. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1970.

Rubin, William S. Frank Stella 1970-1987. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1987.

Information about the exhibition.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2701/2701-h/2701-h.htm

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick e-book.

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=domenico+scarlatti+sonatas

Domenico Scarlatti sonatas on YouTube.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; and Heather Maxson, Manager of School, Youth, and Family Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation; The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation; Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody; Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo and The Dorothea L. Leonhardt Foundation, Inc.; the Barker Welfare Foundation; Con Edison; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Generous endowment support for education programs is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch, Steve Tisch, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by the Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

The Whitney’s Education Department is the recipient of a National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Frank Stella: A Retrospective is jointly organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.