Wild panther lilies thrive in the summer by the misty gray coast. Tucked around eight miles from Highway 1 in San Mateo County is the community of La Honda, where author Ken Kesey lived between 1962 and 1967. When he arrived, leaving behind bohemian Perry Lane in what is now Menlo Park, Kesey was in search of creative isolation. Many homes were summer cabins built around 1929, but ranchers and others lived alongside the vacationers. The houses were spread far apart on the hillside, allowing for significant privacy and freedom.

A man who’d grown up on an old La Honda ranch and had been a teenager when Kesey moved there and began farming pot, uncommon for that time and place, noted that Kesey kept to himself: “My sense was that he was an outlier. You had to live there a long time to be part of that community. I never heard of any parties with him that included established residents.” In fact, as teenagers, the man and his friends would go to the café, one of the few businesses in town, to watch Kesey because he was so different from the locals. Kesey didn’t mix with the community, instead hosting ragers for the writers and artistic types he’d known on Perry Lane.

The author was fairly fresh off the success of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and working on another novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, about a stubborn, freedom-obsessed family in a small Oregon town who cut trees for the local mill despite a strike by a loggers union protesting lower pay as a result of automation. You can see threads of the latter book in the drive into La Honda, if you squint. “And watching, seeing half-remembered farmhouses and landmarks stroking past, I couldn’t quite shake the sensation that the road I traveled moved not so much through miles and mountains, as back, through time.”

When I drive in from the flats one afternoon, a portion of the road that travels directly into the mountains is still closed due to ferocious mudslides during a winter of heavy rain that further isolated an already secluded town. Instead of traveling east through the hills on 84, I take 92 to the coast and then drive south along the ocean to visit Kesey’s former home from the other direction.

The house is set back from the curves of La Honda Road, accessible only by crossing a wooden bridge over the creek. It’s a long cabin made of pine and fir, with red trim, restored and lofted out of the floodplain after extensive damage to the siding from El Nino in 1998. The house, which Kesey would call a Viking lodge and the architecture of which may have been modeled, loosely, on the saltbox houses of Revolutionary War-era New England, is a mile away from what the locals call “town”—an expansive name for a handful of businesses alongside the highway, including a country store, a post office, and Applejack’s, a dive bar known for its colorful patrons, loggers and ranchers still among them.

The house is now owned by a retired couple, Terry Adams and Eva Knodt. Adams is soft-spoken in person, a seemingly unlikely preserver of Kesey’s legacy. He first encountered Kesey in a grad school seminar while on active duty in the air force. At the time, as a budding writer with a conservative father, he thought using psychedelics to write was cheating, but his views evolved. After moving to Palo Alto, he met the psychologist Vik Lovell, the person who introduced Kesey to the CIA experiments with acid and mushrooms underway at the VA hospital in Menlo Park and to whom Kesey dedicated One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, saying Lovell “told me dragons did not exist, then led me to their lairs.” Adams first connected with Lovell at a local psychodrama group and later through an egalitarian men’s group that rejected the egotism of charismatic leaders. The group went backpacking through Big Sur and took LSD and mushrooms ritualistically.

Later, in 1995, when Adams and Knodt had decided to move in together, Adams saw a flyer advertising Kesey’s dilapidated cabin. He ended up taking the flyer to St. Michael’s Alley, then a bohemian Palo Alto hot spot for poetry readings and now an upscale eatery—where Lovell recognized that it was his friend Kesey’s house for sale. When approached by Knodt and Adams, the realtor didn’t take the couple seriously because they weren’t wealthy enough, even though the house, as Adams says, was “terrifically run-down.”

Adams wrote Kesey a long letter explaining that he would try to do something with the legacy of the house, but Kesey didn’t respond. It was Lovell who smoothed the path by vouching for Adams. Adams shares with Kesey certain elements of his life story, including a more conservative upbringing, a growing interest in psychedelics, and a serious literary bent—he would also later publish a book of poetry, Adam’s Ribs.

When the deal on the house closed in July 1997, Kesey, his wife, and his friends came by to reminisce. Kesey pointed out a few things to Adams and Knodt, including the fairy circle of redwoods where the Pranksters would have “heart-to-heart talks,” Adams says. The circle is much smaller than I expected, more intimate for a core group of 14 Pranksters, particularly if the Hells Angels, friends of Kesey’s, showed up.

The woods surrounding the Kesey property are where the police conducted the infamous stakeout for the Pranksters’ drug activity. After Kesey was busted for pot in 1965, he commented, “I have the impression now and then that the community would like to be rid of us.” In 1966, he faked his suicide and fled to Mexico to evade marijuana charges, before serving time at an experimental work camp and moving back to Oregon. Meanwhile, the house was abandoned, though local squatters and people Kesey knew would come to stay. By the time Adams and Knodt moved in, as Adams puts it, “the trash mountain was kind of an archaeological dig,” with accumulated layers of toothpaste, old clothes, and cleaning bottles.

The continued mystique of the Kesey house lies, perhaps, in its careful restoration, completed by Adams and Knodt after the 1998 floods. Though it’s been elevated from the floodplain, the house retains its floor plan. While Kesey was in certain ways forward-thinking for his time (I’m musing on the resurgence in interest in psychedelics as therapeutic agents—he was grossly backward on depictions of race, by today’s standards), there’s a pleasing nostalgia to the things that remain in the house. Adams shows me a doorjamb that retains pencil marks demonstrating the height of Kesey family members, including two marks for Kesey’s son Zane, one in 1964 and one when he was remeasured in 2014. There are surfaces painted by Kesey and the Pranksters—when he was arrested for marijuana, Kesey was painting the toilet. A small piano on a southerly wall is covered on all surfaces with Day-Glo paint. A kitchen door is still layered in the collages of Kesey’s time.

In the space where Kesey’s bus, Furthur, used to rest is a different school bus, one that Adams and Knodt have converted into an RV, complete with a running toilet and a bed. The front panel of the bus says only “ART.” The couple drove the bus down to a parking lot in Palo Alto when the area was evacuated during the wildfires. Beyond the bus on the west side of the property are the woods and the smooth patch of dirt where Kesey kept his writing shack. Long gone, the shack once overlooked the glassy creek where salmon run. While I stand there, the creek is clear and nearly still, reflecting the luminous green and sunlight of the overhead redwoods, a contrast to the “snorting and squalling” Oregon creek of Sometimes a Great Notion.

I can picture Kesey coming out to write among the mystical ferns and redwoods. On psychedelics, the feeling of immensity would be nearly unbearable. Grounding then to concentrate on words, manageable and discrete, over yellow pads of paper or a typewriter. This sorcerous place for Kesey’s writing, perhaps, is what allows for such a strong depiction of small-town life in Sometimes a Great Notion, full of the agitation of a strike yet less disturbing than One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, written on Perry Lane, during a period when Kesey worked as an orderly in the psych facility at the VA and regularly irritated the reserved Wallace Stegner, with whom he workshopped.

In the early days of his ownership of the property, Kesey struggled to get his writer friends to visit him. Decades later, Adams and local novelist Joe Cottonwood cofounded La Honda Lit Night. According to Adams, something like Lit Night has been going on in La Honda since the ’60s. Most of those involved don’t workshop, don’t aspire to get published. They have lively imaginations and like to be heard by those around them, Adams says.

Following the Lit Night readings on the night I visited, the conversation shifted to ChatGPT, and Knodt likened it to a calculator, a shortcut for completing the mechanical elements of composition while freeing minds for larger creativity. Even though Kesey chose a house in this bucolic environment, removed from surveillance, 60 years on, it’s not entirely possible, even here, to escape the advances of Silicon Valley. And while La Honda may have felt to Kesey like a space apart, free from meddling, its severe environmental conditions sometimes require state interventions, as with, for instance, the road repair, which allowed the highway to reopen at the end of July, and those state interventions are sometimes a failure, a friend told me, relating that the fire line was held not by Cal Fire, which was tied up protecting more-populated areas near Santa Cruz, but by locals who’d defied orders to evacuate.

It’s dangerous to write about a place of your heart, especially a place that’s hidden. The act of writing is performative. It performs a revealing, an un-hiding that is, as with ChatGPT, infinitely reproducible and subject to permutation by the other consciousness—or as we see now with that technology, the algorithms—that encounters it. Every piece of writing is also an emotional trip to someplace other than the page, a place in memory or in imagination. It’s not always a trip you want outsiders to take for fear of spoiling it, for fear of the conflicting interpretations that they inevitably bring.

Still, the place in which you write can seep in, unbidden. La Honda saw its early settlement days populated with loggers, like the small town depicted in Sometimes a Great Notion. The conditions its community grappled with—the relationship between human and environment, the dynamics of small communities in the wilderness, the encroachment of technology and automation—remain today. While you can see traces of themes important to La Honda in his depiction of the rural Pacific Northwest, Kesey didn’t expressly set his novels in the town, and it seems likely that this was a conscious decision. He abandoned an unpublished novel he wrote while living in La Honda: One Lane, about Perry Lane. And earlier, Kesey couldn’t escape the slippage of reality into One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Menlo Park’s residue slipping into pages that were set elsewhere, a mental hospital in Oregon. The man who grew up in La Honda told me that his mother had worked with Kesey at the VA hospital during his time as an orderly and could recognize that the abusive Nurse Ratched was clearly modeled after one of her psychiatric nurse coworkers.

Years ago, in a moving work of nonfiction, A Separate Place, the author Charles Jones wrote about outsiders coming to La Honda for a local celebration and destroying things because of the town’s reputation as a place where that wild behavior was acceptable: “It may be common to point to outsiders as troublemakers, but it became terrifyingly real that La Honda was being invaded at least two days a year by people who understood nothing of the place.… A kind of city violence, a city syndrome, had come unchanged into town without regard to the peace that was there if you wanted it.”

Perhaps at some point, Adams and Jones suggest, Kesey was considered one of those destructive forces. But his legend still draws curiosity, shaping what was a space of old time—loggers and ranchers—into a haven for nonconformists seeking freedom, too. “There’s a faction that has a staying power, I think,” Adams says. “It was part of what makes it interesting, what makes it attractive, a fundamental story behind what we do or some of the things we feel strongly about.”•

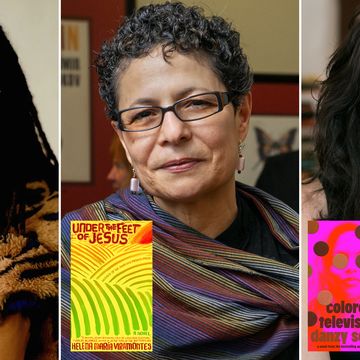

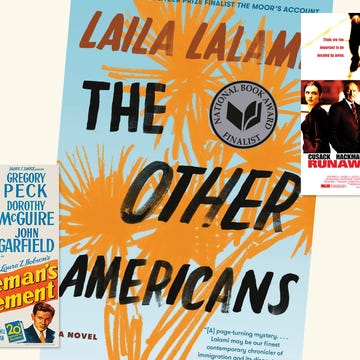

Join us on September 21 at 5 p.m., when Kelly Lytle Hernández will appear in conversation with a special guest and California Book Club host John Freeman to discuss Bad Mexicans. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

EXCERPT

Read the opening pages of Kelly Lytle Hernández’s Bad Mexicans. —Alta

WHY READ THIS

Alta Journal books editor David L. Ulin recommends Bad Mexicans. Hernández’s purpose is “to get things right, but also to give space and agency to the many necessary voices and experiences that have been marginalized.” —Alta

EVENT RECAP

If you missed last week’s CBC event to talk about Naomi Hirahara’s Clark and Division, read a recap or watch the video. —Alta

WHAT HAPPENED

CBC host John Freeman writes about the reconstruction of events through the divulgence of secrets, rumors, and facts in Clark and Division. —Alta

THE POLITICAL IS PERSONAL

Alta assistant editor Jessica Blough suggests four podcasts to listen to after reading Clark and Division. —Alta

LOVE AFFAIR

CBC editor Anita Felicelli reviews William J. Mann’s comprehensive joint biography Bogie and Bacall about the lives of a couple who shared one of the most famous romances in Hollywood. —Alta

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.