Look, Father,” said Edith. “It’s the Pacific Ocean.” Her husband, Will Forbes, seated beside her but more engrossed in the map spread out on his lap than with the actual scenery, responded without looking up: “It’s a bay, dear. San Francisco Bay.” For the father in question, the author and transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, both comments were yet another intrusion. Ever since the observation car had been attached to the train at Emigrant Gap—it was little more than a flat car with a low wall around it and some benches nailed into it—the extraordinarily beautiful views of springtime in the Sierra Nevada had infused his spirit with wonder and melancholy.

All Emerson wanted that day was to observe and ponder. And yet everyone else, his party and a scattering of other travelers gathered on the open-air train car, somehow felt the need to speak, to exclaim, a few of them even to debate the merits of what they were seeing. He loved his daughter and did not show his annoyance. He acknowledged her comment with a brief smile and noticed her gloved hands, her bonnet, the slight change in her figure reflecting her pregnancy. It had never ceased to amaze him that he, neither a monster nor the handsomest of men, and his wife, large-boned and plain, had managed to produce so delicate a beauty.

But bothered he was on this April day in 1871. More than anything else in that moment, despite the affection he felt for his merry group, Emerson wished everyone would be quiet. He wished he could be alone to savor the sentiments coursing through him. Earlier that morning, they had begun their descent from the Sierra foothills into the wide Central Valley, with its woodlands of oak, its lush streams and grassy slopes decorated with pockets of lupine, larkspur, poppies, and hibiscus, and with each passing mile of track, something that he had long suspected and that he had spent considerable energy denying had become more evident: He had waited too long. He should have come here when he was a much younger man. The sensation only increased after leaving Sacramento on this final leg of his journey from New England, one that would bring him to Oakland, the final terminus of the Central Pacific Railroad.

When he was younger and sprier, the dangers and difficulties of transcontinental travel had allowed him to put it off as something to get to later. Back then, the trip had been faced only by tougher folk, adventurers or desperate families willing to risk life and limb for a better future. But in 1869, almost 2,000 miles of track finally connected the lines of the Northeast with new routes laid down from Iowa to Oakland. Given the more settled and genteel society that was taking hold in California in the aftermath of the gold rush, the completion of the rail route was a logical development. Up until then, it had been easier for Emerson—as well as his nearby contemporaries Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Herman Melville—to sail to Europe. The completion of the transcontinental railway changed all that, though it was not a seamless ribbon of gleaming steel track. Rather, it was a potpourri cobbled together by various companies that made some people (the owners and shareholders) very rich, thanks to the labor of many others who were very poor.

Emerson was making the journey as the guest of one of those wealthy railroad men, John Murray Forbes. His oldest son, William, was married to Emerson’s daughter Edith, and the two families had grown close. Forbes’s offer included a snazzy private Pullman Palace Car stocked with goodies and champagne plus a steward and two assistants. This luxurious conveyance accommodated what would be nine travelers. In addition to Emerson and Will and Edith Forbes were John Forbes and his wife, Sarah; their friend Sarah Russell; another friend, Annie Keene Anthony; the younger brother of writer Henry James, Garth Wilkinson “Wilkie” James; and Emerson’s personal lawyer, James Bradley Thayer.

I learned the specifics of Emerson’s journey from Brian C. Wilson’s recent book, The California Days of Ralph Waldo Emerson, which chronicles the trip with an admirable eye for detail and fast-flowing prose. The purpose of Forbes’s invitation was to provide the 67-year-old Emerson with a restful holiday. Exhausted from a series of lecture tours, he was also beginning to exhibit fleeting symptoms of what, a decade later, would spiral into dementia. Even though the discomforts of such a journey were significantly mitigated by the Pullman Palace Car, it was still an arduous undertaking for a man his age.

Eleven days after leaving Massachusetts, the travelers pulled into the Oakland station late in the afternoon and then boarded carriages that took them to the ferry slip. As the steam-driven paddle wheeler got underway with the sun low in the sky, the group enjoyed a clear view of the bustling city and its splendid hills across the bay. Emerson, secretly glad to be free of the overly plush, somewhat claustrophobic Pullman car, stood on deck and breathed in the cool air, which carried a damp scent as invigorating as it was unfamiliar to him, one that blended eucalyptus and salt water. They were now bound for San Francisco’s grandest hotel, the opulent Occidental, an establishment Mark Twain once referred to as “Heaven on the half-shell.”

One can imagine Emerson laying his head down that night on a sumptuous feather pillow, in a city described by Wilson as filled with the “costly luxury of the cosmopolitan future looking out over the crude hucksterism of the fading frontier past.” What would he wake up to? Would this western antithesis to his New England upbringing measure up to how he had imagined it for so many—too many—years?

HIS TRUE NATURE

Emerson was born in Boston into a humble family, and his childhood was one of extreme poverty. His father was a Unitarian preacher who died of stomach cancer just before Emerson turned eight. It was only thanks to his mother’s unstinting work and devotion, and a wise aunt who took an interest in him, that he managed to gain admission to Harvard, where he studied at the divinity school. He eventually became a Unitarian preacher himself, and in 1829 he married a young, wealthy New Hampshire woman, Ellen Tucker, whose family fortune derived from a rope business. She died just two years later, of tuberculosis, at 19, leaving him a childless widower who would then redirect his life.

Emerson began to question his religious faith and drift away from the ministry. He visited Ellen’s grave regularly and did something both astonishing and macabre. Thirteen months after her burial, for a reason no one has been able to explain and about which he left a single written sentence, he had her coffin exhumed and opened for him to contemplate. He did something similar later in life, after a young son from his second marriage died of the same illness. I suspect it was related to his growing respect for science bonded with an insistence on bearing witness to reality—no matter how unpleasant.

He did his best to recover from the loss of his wife by sailing to Europe, traveling to Italy, France, and England. For a man who once stated that “traveling is a fool’s paradise,” it should be noted that this trip to the Old World, when he was 29, affected him profoundly. In Paris, he visited an exhibition at the Jardin des Plantes that brought about an epiphany, one that drew him even further away from his Christian religion. So began his turn toward the wonders of nature and, along with it, his belief in self-reliance. The moment led to the years of writing and lecturing that made him known as a leading figure of 19th-century American transcendentalism, a movement that believes that God is present in nature and humanity, interconnecting them.

In her book American Bloomsbury, Susan Cheever writes that the transcendentalists in their heyday “were the original hippies—young, smart, and dedicated to the overthrow of the stuffy existing authorities [and]…the old Calvinism of the Puritans.” Yet despite their claims to radicalism, the transcendentalists, who also tended to favor the abolition of slavery and the right of women to vote, were mostly Anglo-Saxon males from New England deeply wedded to the traditions and language of Christianity.

In 1834, as this new phase of his life was beginning, Emerson met Lydia Jackson in her hometown of Plymouth, Massachusetts, while he was giving a series of lectures. Emerson was so busy at the time that he proposed to her by mail. The proposal was accepted in kind, and after a July wedding, they—along with Emerson’s mother—settled into a comfortable home in Concord, Massachusetts, where they had four children: two sons and two daughters. Emerson’s reputation and wealth grew, as did his close friendships with Hawthorne, Fuller, and, by way of a dense correspondence, Thomas Carlyle in England.

By the time Forbes invited Emerson to San Francisco, the writer’s hippie days were well behind him. He was an aging, august figure on the American scene, but “the ‘vast West’ that he had long imagined but had not yet seen,” as Wilson describes it, called to him.

Preparing for the trip, Emerson pored over George A. Crofutt’s popular Great Trans-Continental Tourist’s Guide, which, Wilson writes, “offered a philosophy of travel that Emerson himself undoubtedly approved of: ‘Now as you are about to leave the busy hum and ceaseless bustle of the city for the broad sweeping plains, the barren patches of desert, and the grand old mountains—for all these varied features of the earth’s surface will be encountered before we reach the Pacific coast—lay aside all city prejudices and ways…and for once be natural while among nature’s loveliest and grandest creations.’ ”

ALL ABOARD

Emerson and his traveling companions crossed Massachusetts and New York—first in a drawing room car and then in a sleeper car—to Rochester, New York, where they boarded a Pullman Palace Car named the Arlington, which brought them to Chicago. There, Emerson met George Pullman himself, who presented the Forbes entourage with the latest top-of-the-line, luxuriously appointed Palace Car, called the Huron, which would take them the rest of the way.

At various stations along the route, the Huron had to be uncoupled from one train and coupled to another. When a train it was attached to reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, the Huron was loaded onto a barge and ferried across the Missouri River because there was no railroad bridge. Wilson describes the group as getting along splendidly and cites A Western Journey with Mr. Emerson, written by Thayer. The party ate and drank like royalty, enjoyed sightseeing, and engaged in erudite conversations about Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, Rousseau, Wordsworth, and the finer points of German philosophy. They waxed rhapsodic while observing the flora and fauna speeding by and dutifully annotated much of it in their notebooks.

As I read Wilson’s book, I was struck by the absence of any mention of flirtation or friskiness among these people, who were known for their passionate connections to nature. I asked Wilson about it. “If Thayer is to be believed,” he said, “this was a singularly chaste group. Even Edith Forbes’s pregnancy had to be inferred, because it was never mentioned. I can imagine that with the younger members of the party—especially Wilkie James, who was a great favorite with the girls at school—there was indeed quite a bit of flirting and banter going on, perhaps more besides, but I didn’t feel free to speculate or invent.”

One of the stops Emerson wished to make before reaching California was Salt Lake City. Upon arriving in Ogden, Utah, the Huron was removed from the Union Pacific train and attached to a Utah Central locomotive for the short trip south. Emerson was curious to meet Brigham Young, the second president and prophet of the Church of Latter-day Saints, who had been born in Vermont. Wilson writes, “Brigham Young, like Emerson, was a national celebrity, and just as nineteenth-century tourists to Concord were in the habit of dropping in on Emerson unannounced, so, too, tourists in Salt Lake City felt free to do likewise with Young.”

Their encounter occurred one morning with only the males of Emerson’s party in attendance. Young had more than 20 wives and 31 children at the time, and he considered slavery to be “a divine institution.” “It is indeed interesting,” Wilson writes, “that these two Yankees, rough contemporaries of each other, would go on to found such diametrically opposed movements: one that championed ‘self-reliance’ and became the basis of American individualism, and the other championing a rigorous, theocratic communitarianism designed to last into eternity. In some respects, however, they were on the same page. Both, for example, believed that man was a god in the making.”

CITY SIGHTS

San Francisco. April 22, 1871. The Occidental Hotel. Though he was deeply grateful for the largesse of Forbes, surely Emerson was never more so than that morning, while in the privacy of his spacious suite, buttoning his shirt, looking out at the fog dispersing in the sunlight. By this time, the city had a dozen newspapers, many theaters, schools, libraries, churches, museums, and the vast, public Golden Gate Park, designed in part by Frederick Law Olmstead. Andrew Smith Hallidie’s cable car system would not get underway until two years later.

Breakfast was a group affair, in a party for whom anything resembling a dolce far niente view of life was close to anathema. Offered a coach and driver by the Unitarian minister Horatio Stebbins and eager to see the Pacific Ocean, they made their way to the Cliff House. “The journey took them directly through Chinatown,” Wilson writes. “Emerson was fascinated by the ‘China-men’ in their blue robes and ‘long queues reaching almost to their feet,’ whereas Thayer noted the abundance of tea shops, open-air butchers with whole cooked hogs hanging in front, and the ubiquitous laundries advertising their services in English on horizontal signboards and in Chinese on vertical ribbons.”

The wide Cliff House veranda loomed over the beach, offering views out to sea toward the Farallon Islands and down at numerous seals and sea lions lolling on the rocks. From there, Emerson’s group visited Mission San Francisco de Asís, from which the city had adopted its name. The following day was a Sunday, traditionally a holy day, and Emerson was surprised to see so many shops open for business and the city humming along. One evening, accompanied by bodyguards hired through the hotel, they visited an opium den before having dinner at a Chinese restaurant. Watching their food being cooked in plain view was a welcome novelty. On another day, Emerson and Thayer visited a fish market, a local winery, and then the Merchants’ Exchange Building’s library, where they were pleased to note that the 20,000-volume collection was curated by two librarian graduates of Amherst College.

Word of Emerson’s arrival led to requests for lectures. It was not what he had come out there to do. But feeling it impolite to refuse and probably flattered by the attention, he ended up delivering a series of them. He was not at the top of his game at this point, and he basically phoned them in, putting together some old favorites. According to Wilson, the lectures were generally well reviewed by the Daily Alta California but were panned by the San Francisco Chronicle. “As a whole,” the Chronicle reporter summarized, “although abounding in beautiful thoughts and aphorisms, pertinent illustration and apt quotation, the lecture failed in producing the effect, the impression which it may fairly have been expected from a spoken essay by so great a man.”

ALTA CALIFORNIA

After spending a few busy days exploring San Francisco, Emerson wanted to cleanse his palate and experience the natural beauty gracing Alta California. So he, Edith, Will Forbes, and Thayer took a ferry up the bay to Vallejo, where they rode a train 16 miles to Napa and then were driven by carriage to the hot springs of Calistoga. According to Wilson, the spa town was “founded by Brigham Young’s former colleague, Sam Brannan, who, after the gold rush he helped start, had made a fortune in real estate and other enterprises[.] Calistoga was intended to be the ‘Saratoga of California,’ hence the portmanteau name.”

Forbes was waiting there for them, having arrived two days earlier. The following morning, everyone took three carriages 30 miles north to see the geysers, passing through meadows full of yellow flowers and punctuated with groups of oak trees, all the while being serenaded by meadowlarks and red-winged blackbirds. Dinner that evening on the hotel’s veranda consisted of venison, brook trout, fresh eggs, and cream. They fell asleep to the rumblings of the geysers.

The outing that made the most lasting impression on Emerson and his companions began on May 2 when they set off from San Francisco to Yosemite. Getting there required four days of “travel by ferry, railroad, stagecoach, wagon, and finally horseback,” Wilson writes. He describes Forbes as being impressed by Emerson’s stoicism. “Even ‘with the thermometer at 100°,’ he later told Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., Emerson ‘would sometimes drive with the buffalo robes drawn up over his knees, apparently indifferent to the weather, gazing on the new and grand scenes of mountain and valley through which we journeyed.’ ”

Emerson described his first impressions of Yosemite Valley in a journal entry from May 1871: “In Yosemite, grandeur of these mountains perhaps unmatched in the globe; for here they strip themselves like athletes for exhibition, and stand perpendicular granite walls, showing their entire height, and wearing a liberty cap of snow on their head.”

The group stayed at Leidig’s Hotel, a rudimentary but comfortable inn that was still under construction and that commanded an awe-inspiring view of Sentinel Rock. Wilson describes a typical outing: “The day after they arrived, Saturday, May 6, Emerson and most of the rest of the party set off on horseback to Mirror Lake, a journey of several miles up Tenaya Creek. As they rode, Emerson conversed with Mrs. Forbes, and together they recited snatches of Sir Walter Scott back and forth, with Thayer trailing behind, listening intently.” That evening, Emerson wrote in his journal: “A day of wonders…our best day yet.”

It was during this exhausting but exhilarating adventure that Emerson met and befriended John Muir. Born in Scotland, Muir was a bit of a misanthrope, an outdoorsman par excellence who had read some of Emerson’s books and held the transcendentalist, who was considerably older, in great esteem. Their takes on the natural world overlapped. In his biography A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, Donald Worster writes, “Before he had reached the age of twenty, Muir was asking: ‘What creature of all that the Lord has taken the pains to make is not essential to the completeness of that unit—the cosmos?… They are earth-born companions and our fellow mortals.’ ”

“Not only the higher mammals,” Worster goes on to say, “but also insects, reptiles, and plants were in his [Muir’s] view different kinds of ‘people.’ ” According to Wilson, on the last day they spent together, Muir said to Emerson, “You are yourself a sequoia. Stop and get acquainted with your big brethren.”

Muir joined the group for part of their return to San Francisco along the Mariposa route, which would allow them to see Yosemite Valley’s big trees. To move through the shadows of this prehistoric forest, made up of the largest trees in the world, which grew only there and nowhere else and which were among the oldest organisms on Earth, must have been close to a spiritual experience for Emerson. At one point, he was encouraged to claim a tree so it would be named for him, but Emerson, embarrassed, refused. (One was named for him posthumously.) Muir tried his best to get the group to stay longer, implying that it would be almost a sacrilege to spend so little time there. But Emerson was tired by then and turned him down. Muir would go on to become a much-celebrated figure until, in our times, he was criticized for his racism. In 2020, the Sierra Club, which he cofounded in 1892, publicly refuted those views of his.

Throughout his book’s first seven chapters, Wilson concentrates on Emerson and his journey, and he refrains from issuing any moral judgment. But in his last chapter, Wilson tells us how Thayer, later an esteemed law professor at Harvard, defended the outrageous Dawes Act of 1887, which led to the massacre at Wounded Knee three years later. Wilson adds, “Of course, looking at the trip through twenty-first-century eyes…the largely unacknowledged historical complexity of the West and the barely acknowledged human diversity of the region…was either deprecated when noticed, such as with the American Indians, the Chinese, and Irish, or totally invisible, such as with the African Americans who undoubtedly served them as porters on the train.”

BACK EAST

Emerson’s final days in San Francisco were busy. He and the other men in his troupe attended a raucous, down-and-dirty theater performance at one of the so-called melodeons, a string of theaters found along the Barbary Coast waterfront. The next day, everyone except for Emerson and the pregnant Edith traveled to the Peninsula and explored Valparaiso Park, the vast estate of shipping magnate Faxon Dean Atherton, who was originally from Dedham, Massachusetts. Father and daughter remained in the city, visiting the photo studio and gallery of Carleton Watkins.

Then came the morning of May 19. Emerson and his party left the Occidental Hotel and returned by ferry to the Oakland train station, only to be told that the arrival of their Pullman Palace Car would be delayed by a few days. At the instigation of Forbes, they used the time to go fishing for trout at Lake Tahoe.

Emerson’s final evening in California was spent at a Nevada inn just over the state line. According to Wilson, Edith and her father sat on a porch overlooking the lake, watching “the sunset light on the snowy mountains—the opal tints and clear yellow sky in the southern horizon.” Emerson was pleased to see “the minute new moon, and when that had set the evening star was so bright it made a path of light across the water, and the dashing water against the rocks made the last perfecting charm.”

Emerson and Muir remained in touch, and in numerous letters, Muir pleaded for Emerson to make a return visit to California. But after a trip to Europe and to Egypt, Emerson stayed put in his beloved Concord, where he would remain until his death in 1882.

While approaching his seventh decade, Emerson had done the improbable. He had explored and experienced what might well have been a road better taken in his youth. If only temporarily, he had exchanged his stark New England for the promise, the openness, and the beauty of California that he had dreamed about. The temptation to go back there, then older and closer to his end, was still great. Not long before he died, Emerson told his publisher, “We must not visit San Francisco too young, or we shall never wish to come away.”•

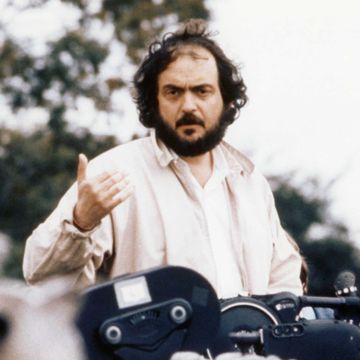

John J Healey is the author of five novels. He lives in the Berkshires of Massachusetts and in Spain. He studied medicine in Granada, Spain but left the field and began a 12-year career in motion pictures. In 1998, Healy directed the documentary Federico García Lorca and in 2010 The Practice of the Wild, a portrait of poets Gary Snyder and Jim Harrison.

His first novel Emily & Herman was published in 2013, followed by The Samurai of Seville, in 2016. Its sequel, The Samurai's Daughter, was published in 2019. A fifth novel, April in Paris, was published by Arcade in July 2021.