Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

David Blight’s massive and masterful biography of Frederick Douglass describes a brief encounter that occurred in 1877. President Rutherford B. Hayes has appointed Douglass marshal of the District of Columbia, making the former slave and renowned abolitionist the first African American to be nominated for a government position requiring Senate approval. A bailiff approaches a man to ask “if he was looking for Marshal Douglass,” and the man, a onetime constable, replies, “No, sir, not now; but there was a time, when he was a fugitive slave, when I tried hard to find him.”

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

In Stock Online

Hardcover

$33.49

$37.50

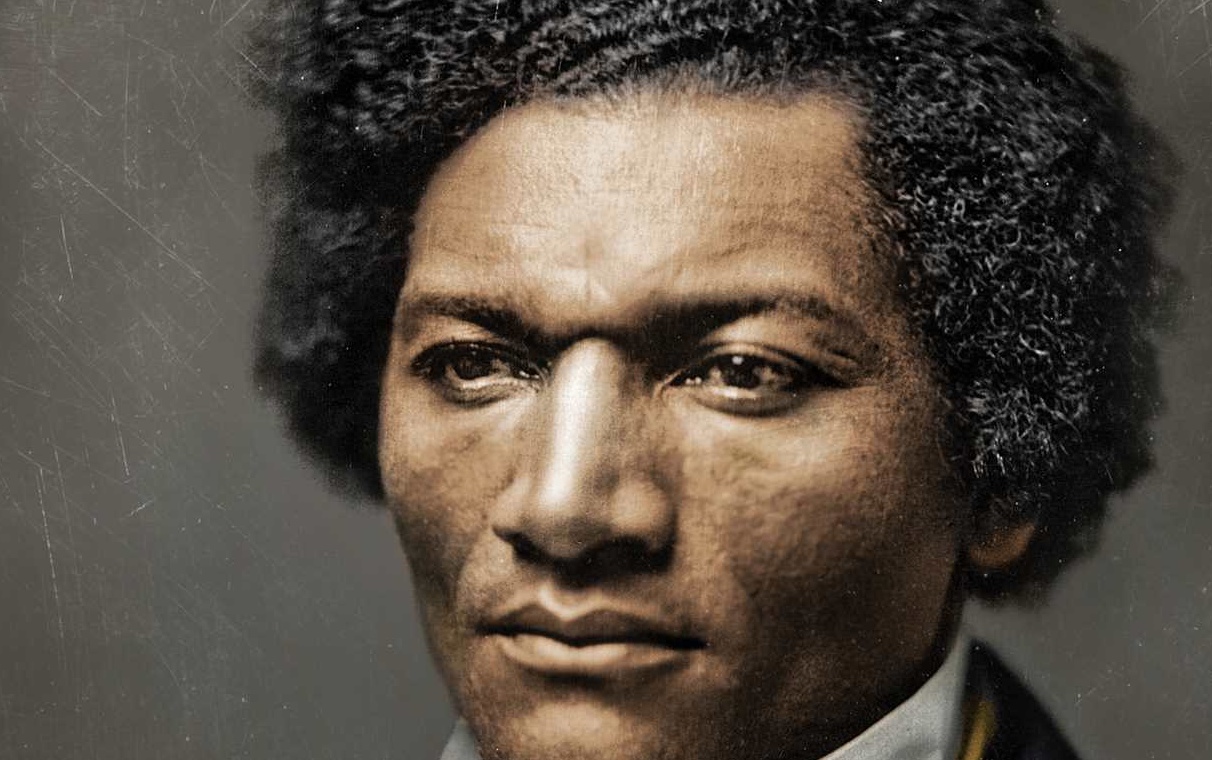

This is one of many moments in Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom when the reader is filled with wonder at the sheer unlikelihood of Douglass’s extraordinary American life. Born into bondage on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1818–his white owner was likely his father, but he was never able, despite lifelong effort, to confirm either the truth of his paternity or his birthdate–Douglass was a slave for 20 years and a fugitive for nine, before a group of abolitionist friends purchased his freedom. He was, during his lifetime, the most famous black man in the world, and he was the most photographed American of the 19th century. For more than five decades he maintained a crushing schedule criss-crossing the country giving speeches, first on the abolition circuit and then, after the Civil War, in an effort to compel his country to live up to the failed promises of emancipation. He was also the author of three widely read and now classic autobiographies, in which he constantly revisited and reassessed his past.

Endeavoring to tell the life story of somebody who told his own life story so often and so well surely has its pitfalls. Indeed, Blight concedes from the outset that “confronting the autobiographer in Douglass is both a pleasure and a peril as his biographer.” The author, an American history professor at Yale and a Douglass scholar of many decades, manages the task beautifully, quoting liberally from his subject’s brilliant books, speeches, and articles (Douglass edited several newspapers throughout his long career) while providing context on his eventful times, his friendships and rivalries, and his enduring relevance. Significantly, Blight also probes the absences in Douglass’s body of work, particularly as they pertain to his first wife, Anna, who was born free and helped Douglass escape from bondage but who remained illiterate throughout her life.

The luckiest break of Douglass’s early years occurred in 1826, when he was sent from an Eastern Shore plantation to his owner’s extended family in Baltimore, a bustling port city with a large population of free blacks. He would be sent to and from Baltimore over the years, until his final escape in 1838. But during his first stay, his new mistress, before her husband put a stop to it, taught the eager young Frederick to read. As a teenager he managed to acquire a school reader called The Columbian Orator. The compilation of prose, poetry, and speeches covered a variety of topics, including a debate over slavery. Blight movingly imagines the teenage Douglass grasping for the first time “that slavery was subject to ‘argument.’” The reader was one of the few possessions Douglass carried with him as a fugitive, and he treasured the book to the end of his life.

In addition to constant hunger, Blight writes, “boredom, rage, and a growing intelligence mixed to make Frederick a troublesome slave.” At age 16 he was sent for a year to a cruel and sadistic overseer on the Chesapeake Bay to be “broken,” an experience he described wrenchingly in 1845’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Not long after his escape to the North, Douglass entered the orbit of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, the mentor who launched the younger man’s career as an orator after hearing him describe his experiences in bondage. “I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment,” Garrison wrote of the first time he heard the mesmerizing Douglass speak.

The two eventually had an acrimonious break when Douglass could no longer subscribe to Garrisonian pacifism. He had too much righteous fury. “I have no love for America, as such. I have no patriotism. I have no country,” he declared in a fiery 1847 speech. Elsewhere, he called the Bill of Rights, to blacks, “a bill of wrongs. Its self-evident truths are self-evident lies.” Only with the outbreak of the Civil War, which Douglass welcomed, did the former slave begin to identify as an American. In Douglass’s view, Blight writes, “during the final year and a half of the Civil War one America died a violent, necessary death; out of its ashes a second, redefined America came into being amid destruction and explosions of hope.” He was convinced, the author adds, that “the American nation, and history itself, had taken a rare, fundamentally moral turn.

Of course, the years after the war brought crushing counterevidence to that view, from the Supreme Court’s gutting of the 14th Amendment to the unchecked terror wrought against Southern blacks through voter suppression, lynching, and mob violence. In the face of these bitter setbacks, Douglass’s radicalism gave way to pragmatism; the subversive outsider transformed himself into a political insider in a bid to effect change. Douglass always urged blacks to remain loyal to the party of Lincoln, observing, as Blight puts it, that “they might sometimes be ‘slighted’ by Republicans…but they were ‘murdered’ by Democrats.”

Douglass, a fierce individualist, also preached self-improvement and self-reliance to his black audiences, a message that sometimes fell flat to listeners who were struggling to survive and thwarted at every turn. Still, for that reason, some Republicans today try to claim Douglass’s mantle. Blight uses his subject’s own words to set them straight. As the nation tragically retreated from political and social equality for blacks, deferring to states’ rights and enabling the rise of Jim Crow, Douglass made clear where he stood on the issue of activist government. “If the general government had the power to make black men citizens, it has the power to protect them in that citizenship,” he argued. “If it had the right to make them voters it has the right to protect them in the exercise of the elective franchise.”

Given the fullness of Douglass’s life, its momentousness and its contradictions, it’s little surprise that there is quarrel over his legacy. As a young man he faced the lash; as an adult he conferred with President Lincoln in the White House. He worked relentlessly to support a large and often contentious extended family whose members relied on him for financial help. He buried two children and ten grandchildren. He never stopped forcing America to face her hypocrisies. After his late-in-life second marriage, to a white woman 20 years his junior, caused a scandal, Douglass pointed out the million Americans of mixed blood resulting from the sexual exploitation of black slave women by their white masters. “It would seem that what the American people object to is not the mixture of the races,” he noted, “but honorable marriage between them.”

Douglass reached untold numbers of Americans during his lifetime, and his words and thinking live on, still challenging us today. As the author elegantly puts it, “‘Why am I a slave?’ is an existential question that reflects as well as anticipates many others like it in human history. Why am I poor? Why is he so rich, and she only his servant or chattel? Why am I hated for my religion, my race, my sexuality, the accident of my birth in this valley or on that side of the river or on this side of the railroad tracks?…Douglass’s story represents so many others over the ages.” In Blight’s able hands, its many lessons are brought, relevant and alive, into the 21st century.

This is one of many moments in Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom when the reader is filled with wonder at the sheer unlikelihood of Douglass’s extraordinary American life. Born into bondage on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1818–his white owner was likely his father, but he was never able, despite lifelong effort, to confirm either the truth of his paternity or his birthdate–Douglass was a slave for 20 years and a fugitive for nine, before a group of abolitionist friends purchased his freedom. He was, during his lifetime, the most famous black man in the world, and he was the most photographed American of the 19th century. For more than five decades he maintained a crushing schedule criss-crossing the country giving speeches, first on the abolition circuit and then, after the Civil War, in an effort to compel his country to live up to the failed promises of emancipation. He was also the author of three widely read and now classic autobiographies, in which he constantly revisited and reassessed his past.

Endeavoring to tell the life story of somebody who told his own life story so often and so well surely has its pitfalls. Indeed, Blight concedes from the outset that “confronting the autobiographer in Douglass is both a pleasure and a peril as his biographer.” The author, an American history professor at Yale and a Douglass scholar of many decades, manages the task beautifully, quoting liberally from his subject’s brilliant books, speeches, and articles (Douglass edited several newspapers throughout his long career) while providing context on his eventful times, his friendships and rivalries, and his enduring relevance. Significantly, Blight also probes the absences in Douglass’s body of work, particularly as they pertain to his first wife, Anna, who was born free and helped Douglass escape from bondage but who remained illiterate throughout her life.

The luckiest break of Douglass’s early years occurred in 1826, when he was sent from an Eastern Shore plantation to his owner’s extended family in Baltimore, a bustling port city with a large population of free blacks. He would be sent to and from Baltimore over the years, until his final escape in 1838. But during his first stay, his new mistress, before her husband put a stop to it, taught the eager young Frederick to read. As a teenager he managed to acquire a school reader called The Columbian Orator. The compilation of prose, poetry, and speeches covered a variety of topics, including a debate over slavery. Blight movingly imagines the teenage Douglass grasping for the first time “that slavery was subject to ‘argument.’” The reader was one of the few possessions Douglass carried with him as a fugitive, and he treasured the book to the end of his life.

In addition to constant hunger, Blight writes, “boredom, rage, and a growing intelligence mixed to make Frederick a troublesome slave.” At age 16 he was sent for a year to a cruel and sadistic overseer on the Chesapeake Bay to be “broken,” an experience he described wrenchingly in 1845’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Not long after his escape to the North, Douglass entered the orbit of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, the mentor who launched the younger man’s career as an orator after hearing him describe his experiences in bondage. “I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment,” Garrison wrote of the first time he heard the mesmerizing Douglass speak.

The two eventually had an acrimonious break when Douglass could no longer subscribe to Garrisonian pacifism. He had too much righteous fury. “I have no love for America, as such. I have no patriotism. I have no country,” he declared in a fiery 1847 speech. Elsewhere, he called the Bill of Rights, to blacks, “a bill of wrongs. Its self-evident truths are self-evident lies.” Only with the outbreak of the Civil War, which Douglass welcomed, did the former slave begin to identify as an American. In Douglass’s view, Blight writes, “during the final year and a half of the Civil War one America died a violent, necessary death; out of its ashes a second, redefined America came into being amid destruction and explosions of hope.” He was convinced, the author adds, that “the American nation, and history itself, had taken a rare, fundamentally moral turn.

Of course, the years after the war brought crushing counterevidence to that view, from the Supreme Court’s gutting of the 14th Amendment to the unchecked terror wrought against Southern blacks through voter suppression, lynching, and mob violence. In the face of these bitter setbacks, Douglass’s radicalism gave way to pragmatism; the subversive outsider transformed himself into a political insider in a bid to effect change. Douglass always urged blacks to remain loyal to the party of Lincoln, observing, as Blight puts it, that “they might sometimes be ‘slighted’ by Republicans…but they were ‘murdered’ by Democrats.”

Douglass, a fierce individualist, also preached self-improvement and self-reliance to his black audiences, a message that sometimes fell flat to listeners who were struggling to survive and thwarted at every turn. Still, for that reason, some Republicans today try to claim Douglass’s mantle. Blight uses his subject’s own words to set them straight. As the nation tragically retreated from political and social equality for blacks, deferring to states’ rights and enabling the rise of Jim Crow, Douglass made clear where he stood on the issue of activist government. “If the general government had the power to make black men citizens, it has the power to protect them in that citizenship,” he argued. “If it had the right to make them voters it has the right to protect them in the exercise of the elective franchise.”

Given the fullness of Douglass’s life, its momentousness and its contradictions, it’s little surprise that there is quarrel over his legacy. As a young man he faced the lash; as an adult he conferred with President Lincoln in the White House. He worked relentlessly to support a large and often contentious extended family whose members relied on him for financial help. He buried two children and ten grandchildren. He never stopped forcing America to face her hypocrisies. After his late-in-life second marriage, to a white woman 20 years his junior, caused a scandal, Douglass pointed out the million Americans of mixed blood resulting from the sexual exploitation of black slave women by their white masters. “It would seem that what the American people object to is not the mixture of the races,” he noted, “but honorable marriage between them.”

Douglass reached untold numbers of Americans during his lifetime, and his words and thinking live on, still challenging us today. As the author elegantly puts it, “‘Why am I a slave?’ is an existential question that reflects as well as anticipates many others like it in human history. Why am I poor? Why is he so rich, and she only his servant or chattel? Why am I hated for my religion, my race, my sexuality, the accident of my birth in this valley or on that side of the river or on this side of the railroad tracks?…Douglass’s story represents so many others over the ages.” In Blight’s able hands, its many lessons are brought, relevant and alive, into the 21st century.