My Cartooning: John Updike

I can’t remember the moment when I fell in love with cartoons. Almost certainly it was an image out of the Disney studio, which in the 1930s pervaded popular culture, including cheap (10 cents) books for children. I still have a Donald Duck, on oilclothy paper in big format, and remember a smaller, cardboard-covered book based on the animated cartoon of the Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf.

It was the intense stylization of those images, with their finely brushed outlines and their rounded and buttony furniture and their faces so curiously amalgamated of human and animal elements, that drew me in, into a world where I, child though I was, loomed as a king, in a realm where my parents and other grownups were strangers. I became an expert. Spread out on the floor with my crayons and colored pencils, I taught myself to copy cartoons—I can still do a serviceable Mickey Mouse—and by the age of six or so was copying many of the syndicated comic characters of the day: Popeye and his rubber-legged sweetheart, Alley Oop on his dinosaur, Barney Google, Dagwood, Dick Tracy. I don’t believe I attempted the more naturalistic style of Milton Caniff and Alex Raymond and Hal Foster, but certainly I entered into their adventures, each panel like a separate door into the same magical large room.

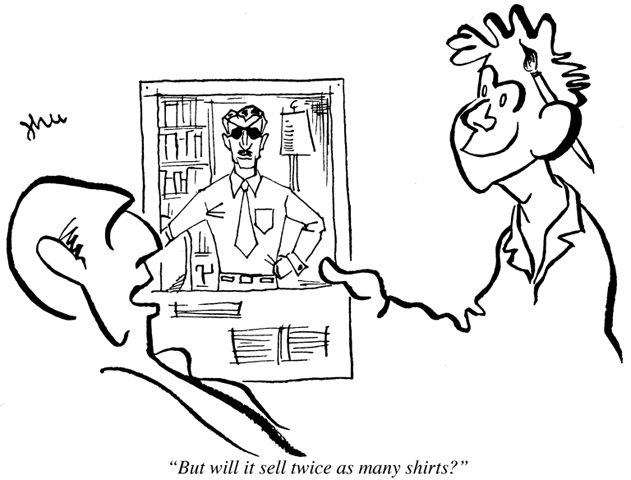

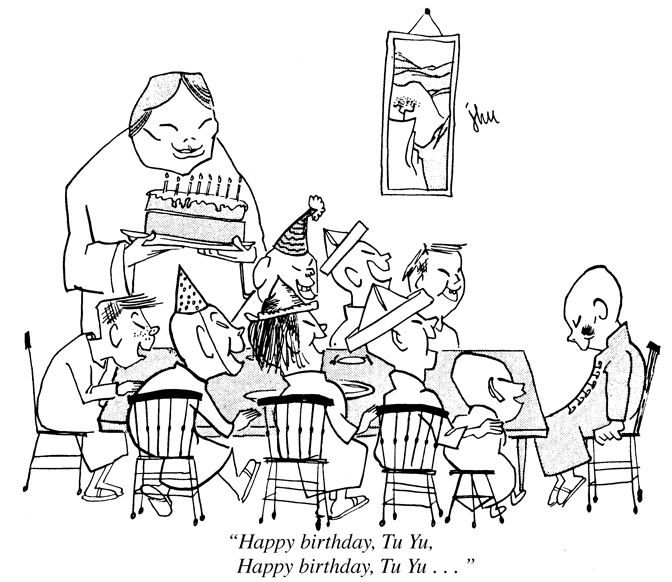

The Disney cartoons at the movies, which my parents took me to from the age of three on, and which I began to attend alone at the age of six, composed another corner of this room, dazzlingly bright and busy. I recently acquired the video of Snow White, and the procession of dwarves home from the diamond mine, and the fluttering of the birds that shepherd Snow White through the forest, seemed as marvelous and poignant as when I first saw it in 1937, at the age of five. For a time I dreamed of being a Disney animator, dreams fed by those documentary films of his which displayed his studio and revealed the details of animation’s technology. I copied comic-strip characters on plywood and cut them out with a coping saw; I scissored the strips out of the daily newspaper and made little books of them; I drew caricatures of my classmates; I became the class poster-maker. I sent fan letters to comic-strip artists and sometimes got back original strips in return. The arrival of The New Yorker at our house when I was 11 or so shifted my ambition toward single-gag magazine cartoons, which appeared not only in The New Yorker but Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post and many lesser magazines. Arno, Chon Day, Cobean, Thurber, Gluyas Williams, Robert Taylor, Garrett Price—I pored over them and could identify their styles, to the mild amusement of my friends, upside-down, flipping the pages rapidly.

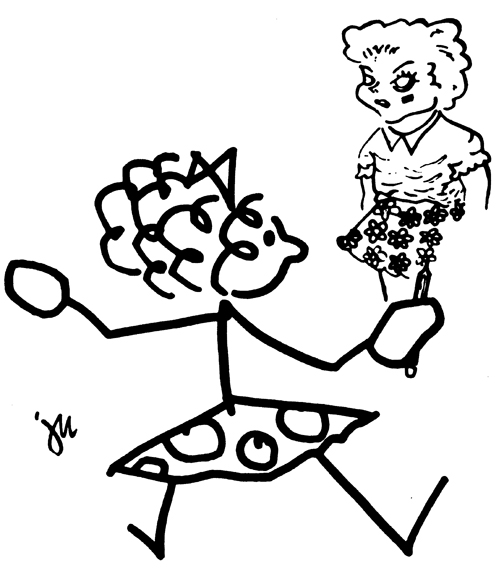

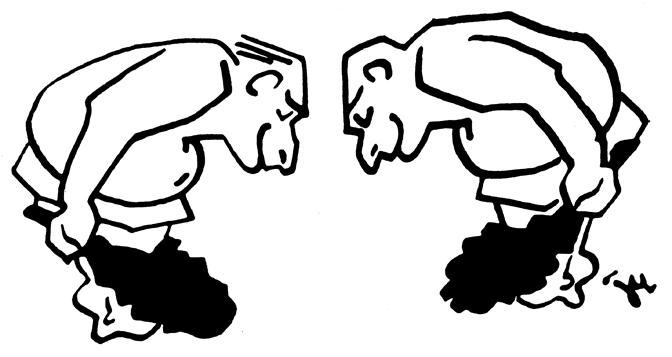

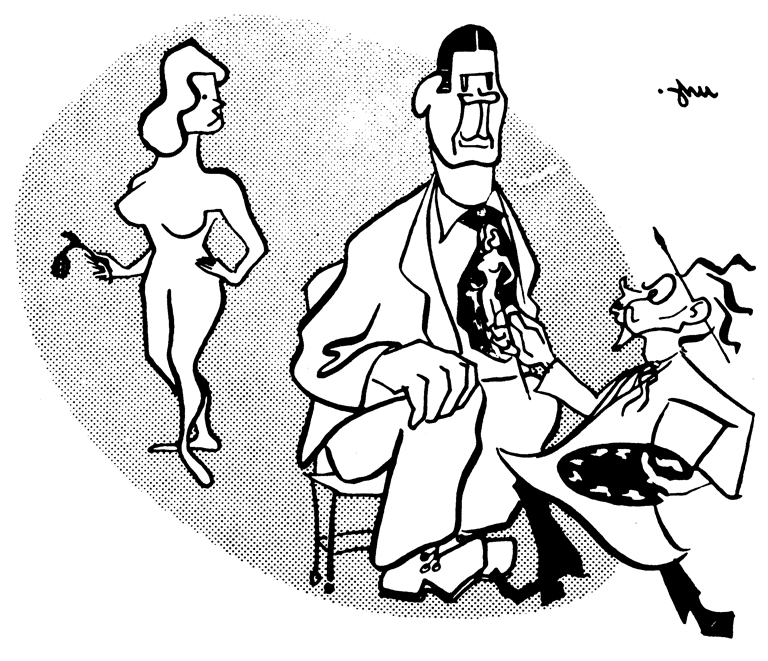

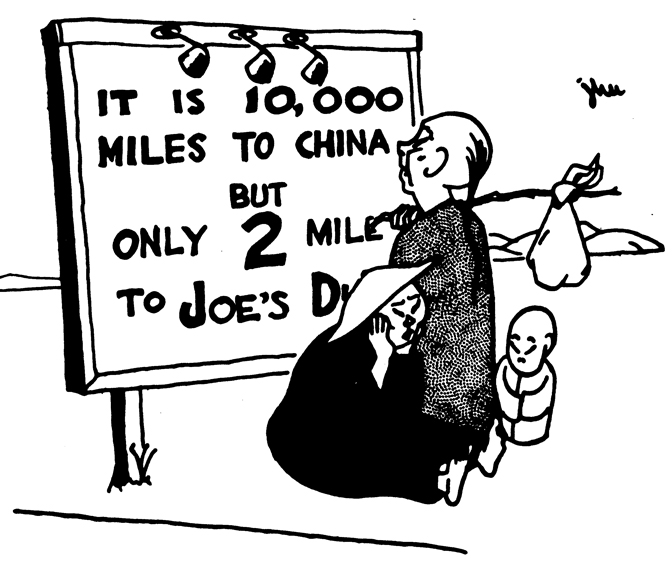

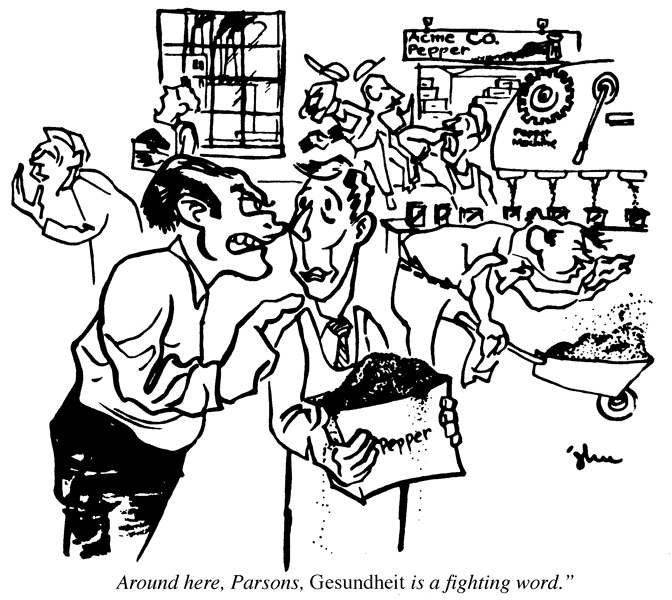

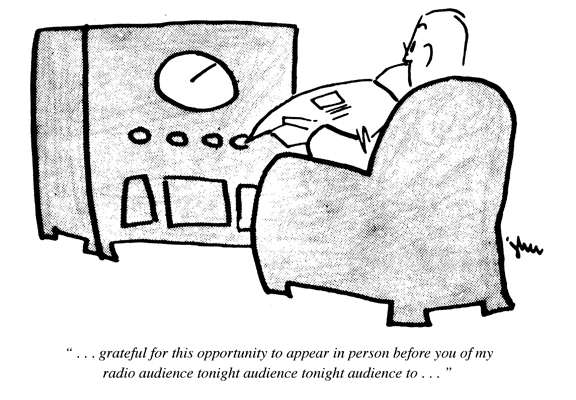

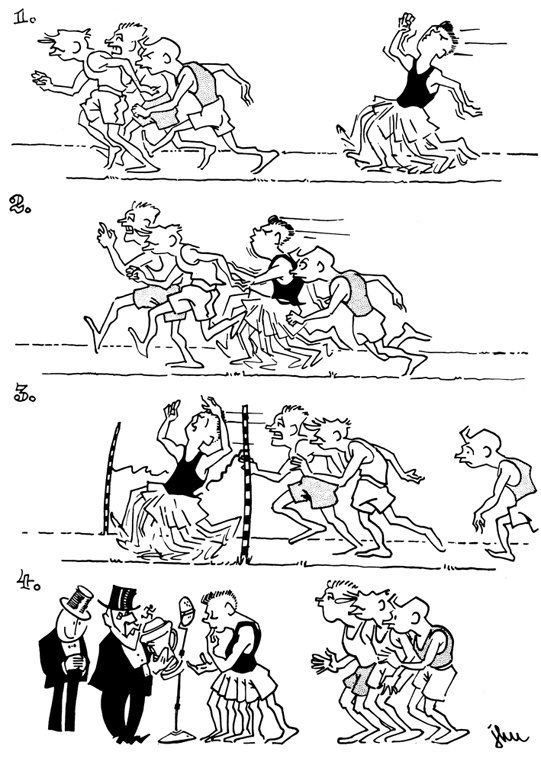

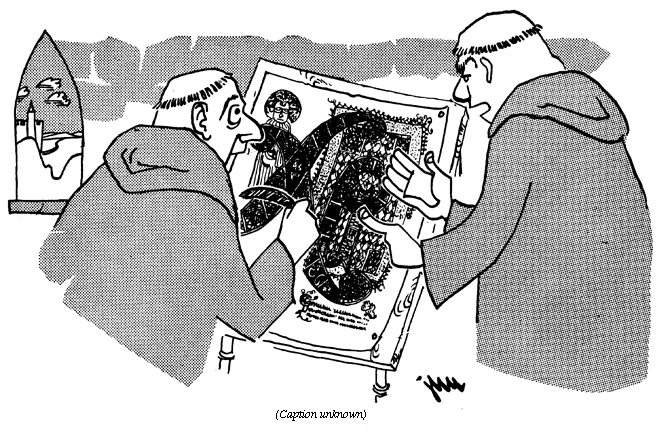

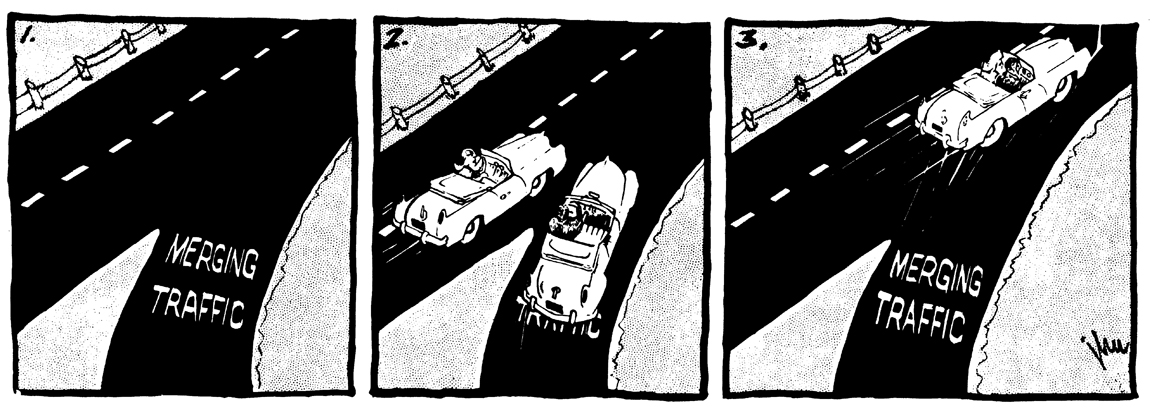

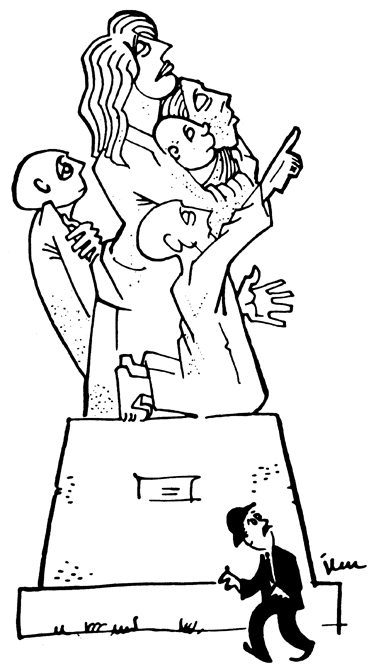

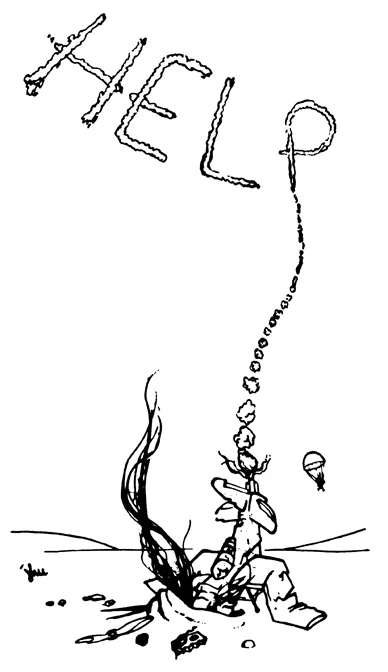

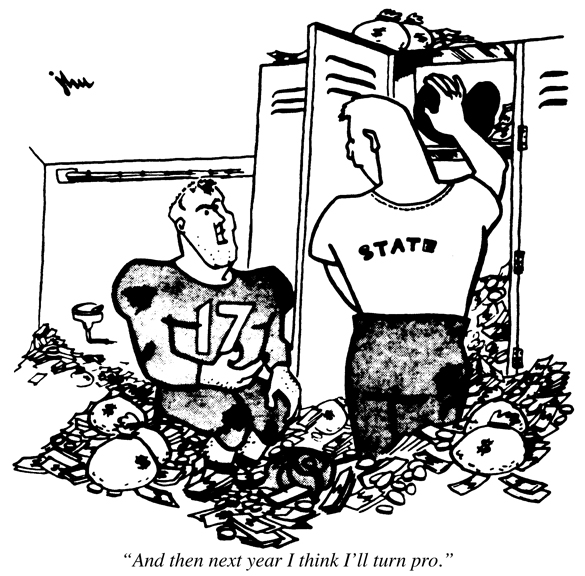

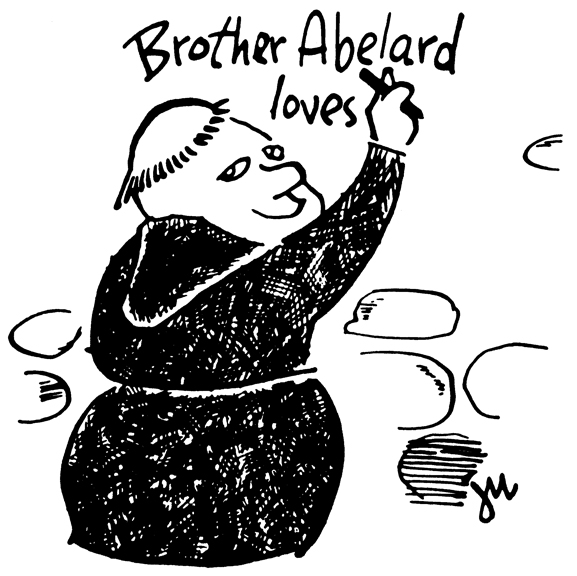

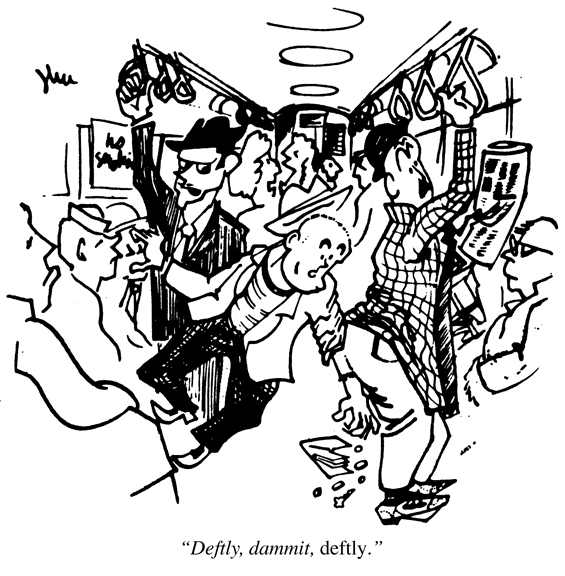

I was 14 or 15 when I first began to send out “roughs” to these same magazines; I even bought myself a rubber stamp with my name on it, since I read that that was what the pros did. I didn’t crack The New Yorker, but I did once sell (for $5) a dairymen’s journal a cartoon of a milk-truck with a running cow instead of a greyhound on it, and when I went to Harvard I was elected to the Harvard Lampoon on the strength of my cartooning. The Lampoon, which had begun in the 1870s as an imitation of Punch and had imitated Judge and Life in the ’20s, by the ’50s was an imitation of The New Yorker, which suited me fine. A college publication, with its lazy and distracted staff, gives wonderful scope to the creative spirits willing to work. I wrote light verse and humorous prose as well as drew for the Lampoon and occupied in turn all three literary offices—Narthex, Ibis and President. All the cartoons and spot drawings here were published in its pages before June 1954 and have lost something in the reproduction. The quality of halftone reproduction, as well as its expense, led one to rely on black-on-white, with shading laid in either by me with razor blade and transparent Benday or by the printer, over a blue wash. They represent my peak as a cartoonist. Just to look at them revives for me the excitement of laying wet India ink on a sheet of Bristol board, under a close hot gooseneck lamp, late at night. The process in fact got me so excited I usually smeared a wet line or two, in my haste to get on with it.

By the time I graduated in 1954 I was 85 percent bent upon becoming a writer; it took fewer ideas, and I seemed to be better at it. Also, one can continue to cartoon, in a way, with words; whatever crispness and animation my writing has, I credit the cartoonist manqué.