Born into slavery in 1818, it’s likely that Frederick Douglass wore rags as a child. But he borrowed the clothing of a seaman and stole away to freedom in 1838.

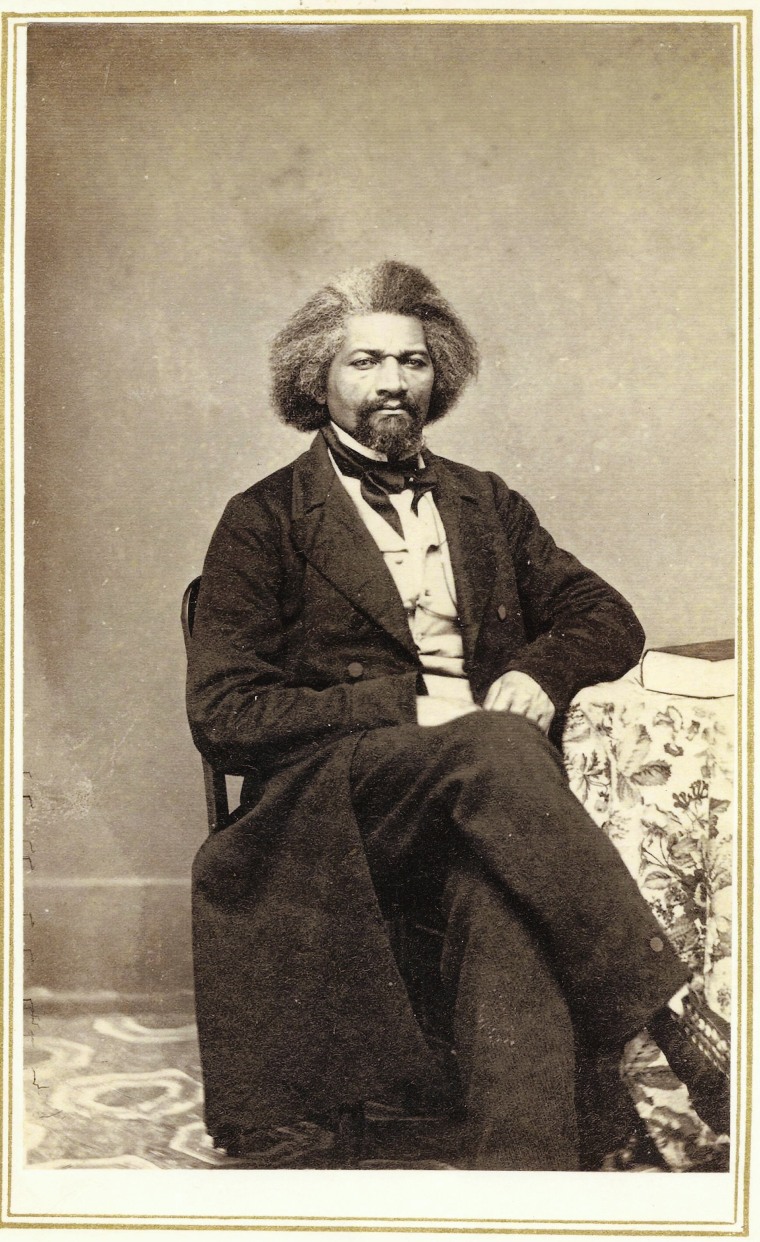

As an abolitionist, author, and adviser to U.S. presidents, he donned luxurious ascots, vests and overcoats.

Historians know this because 160 distinct portraits of him exist — compared to only 126 of President Lincoln. An exhibit at the Museum of African American History shows many of these photos. So does a coffee table book Picturing Frederick Douglass published last year which identifies the legendary leader as the most photographed American of the 19th century.

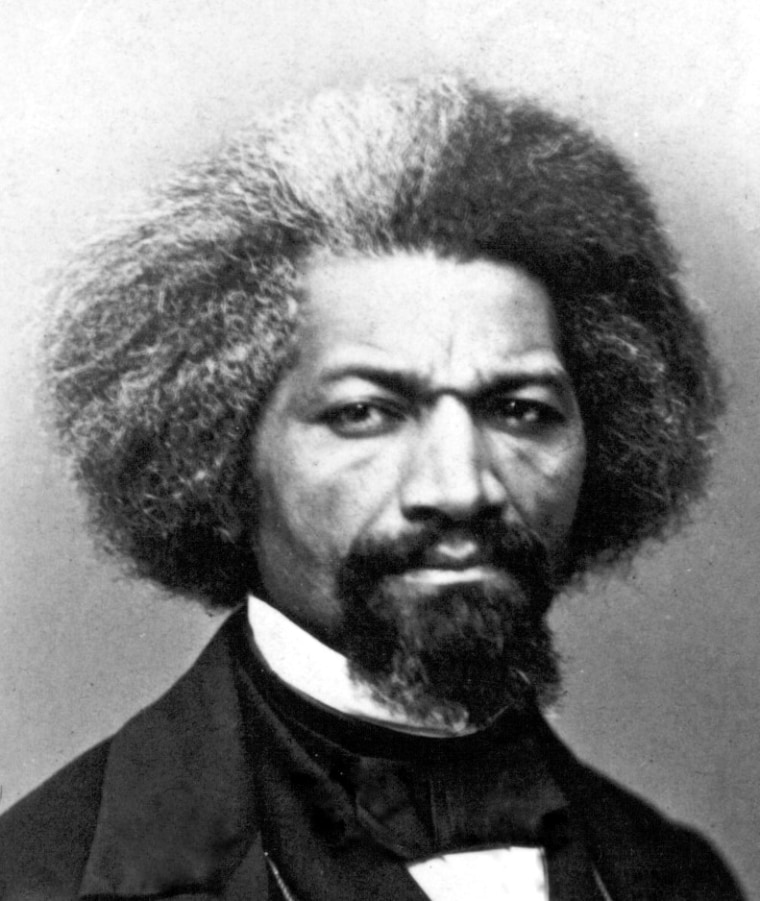

For him, it wasn’t about styling and profiling. Douglass “viewed photography as art and technology,” according to authors John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd and Celeste-Marie Bernier.

He felt the new medium, born around the same time that he escaped slavery, could displace whites’ preconceived notions of blacks. Unlike laughable caricatures and menacing drawings, he saw photography as objective and highlighted “the essential humanity of its subjects.”

Douglass frequented photographers’ studios, and gave four talks on photography, including "Lecture on Pictures", "Life Pictures", "Age of Pictures" and "Pictures and Progress". He used his image to garner subscriptions to his newspaper, The North Star.

And he frequently gave his photographs to family and friends. His popular image sometimes ended up on the walls of people who never met him.

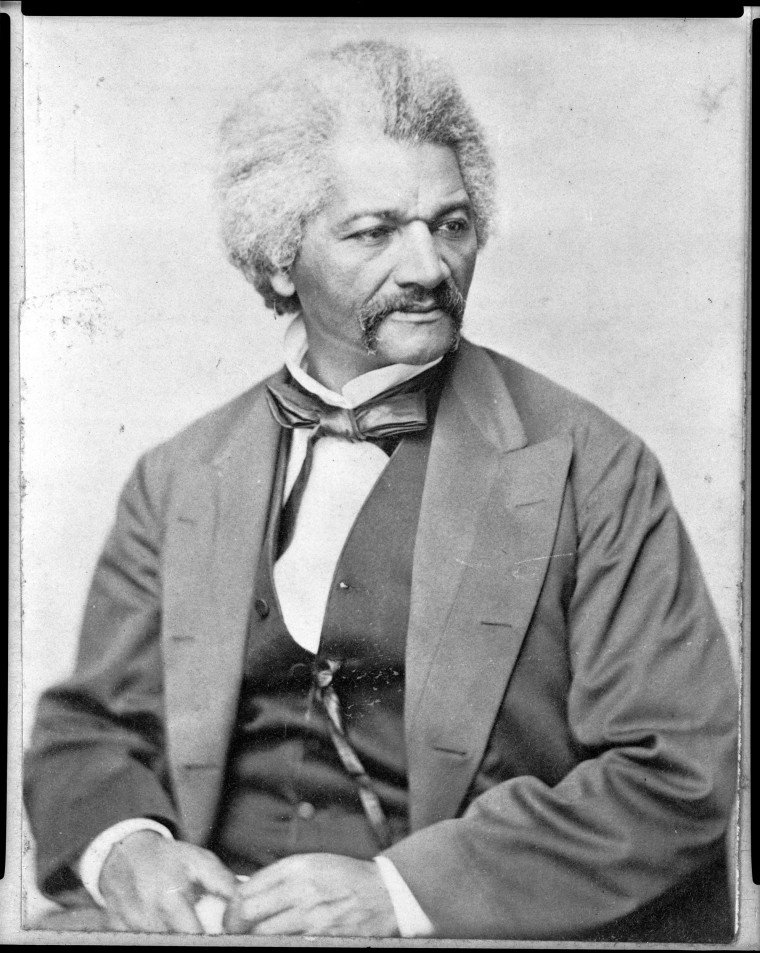

The continuum of portraits date from Douglass’ early years as a thin man with strong features and thick black hair, to his middle and later years as his face and body widened and his mane grayed. The final image was taken on his deathbed a day or two after he passed.

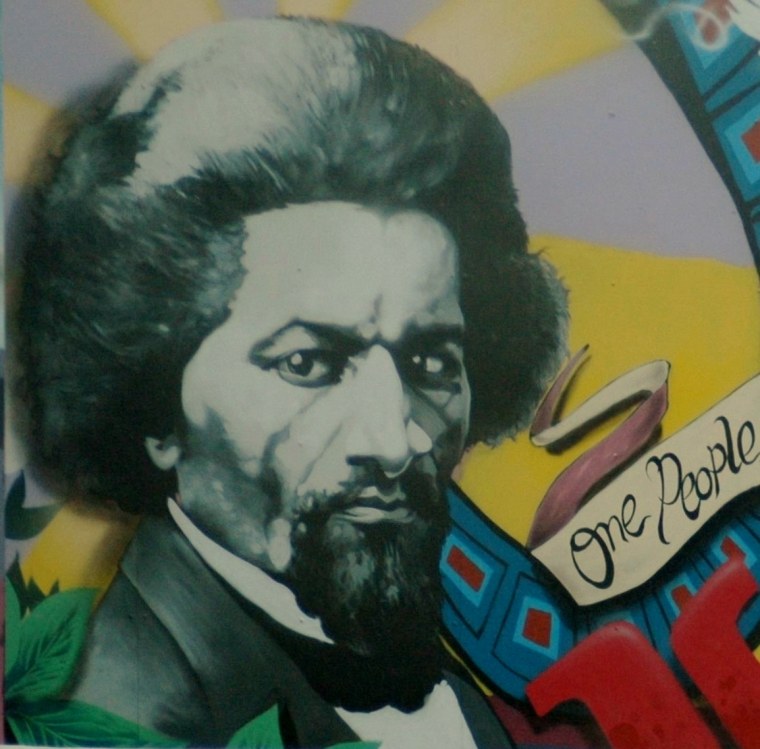

“Through the dissemination of his image and word, Douglass photographed and wrote himself into the public sphere,” the authors propose, until he “became the most famous black man in the western world, and thus acquired cultural and political power.” Douglass’ iconic image of defiance and freedom continues to be the muse of artists around the world.

RELATED: The Black History Month Debate is Back

During his lifetime, though, he carefully protected his portrayal: When one engraver, using an early reproduction method, gave him a smile, Douglass protested the misrepresentation of “the face of a fugitive slave.” (Although in one portrait, he did smile slightly.) He also poses with second wife, Helen, and in another portrait sits as grandson, Joseph, stands playing a violin.

In additional to presaging the concept of branding, Douglass served as his own stylist. In one series of photos, for example, his overcoat was said to be undone, hung loosely, and/or was creased. But in the image he approved for sale and distribution, the coat appears smooth and camera-ready.

Douglass’ descendant Kenneth B. Morris, Jr., who provided the afterword, writes:

“I was not surprised to learn that Frederick Douglass had the foresight to skillfully use the emerging medium of photography to shape his public image and define himself as a free man and citizen in the public consciousness.”

Morris is not only Douglass’ great-great-great-grandson, but also the great-great grandson of Booker T. Washington. Morris’ grandmother Nettie Hancock Washington and grandfather Dr. Frederick Douglass III met on Tuskegee’s campus in 1941 and married three months later.

That was possible because, nearly a century earlier, a photographer—who was also a telegraph operator—saved their ancestor’s neck. Douglass had arrived in Philadelphia in 1859 to give a speech at the same time that news broke of John Brown's capture at Harper's Ferry.

A sheriff ordered Douglass’ arrest as a Brown co-conspirator. But White suppressed delivery of the message for three hours, worked with a local Underground Railroad operator, and helped Douglass escape Philadelphia and ultimately leave for England: A most fortuitous moment to step out of the picture.