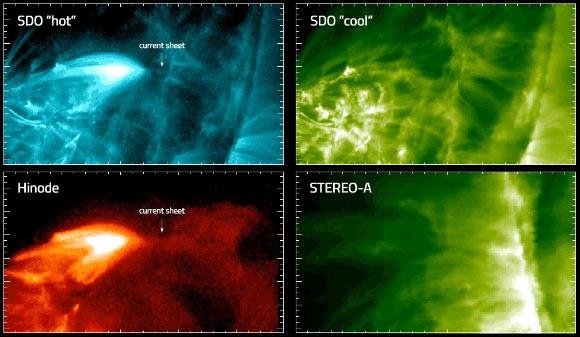

During a December 2013 solar flare, three solar-watching satellites — NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), the agency’s Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), and JAXA/NASA’s Hinode — observed an electromagnetic phenomenon called a current sheet, a strong clue for explaining what initiates solar flares.

This picture shows four views of the 10 December 2013 solar flare from SDO, STEREO, and Hinode. The current sheet is a long, thin structure, especially visible in the views on the left. Image credit: NASA / JAXA / SDO / STEREO / Hinode / Zhu et al.

Solar flares are powerful outbursts of electromagnetic radiation from the Sun lasting from minutes to hours.

They are created when magnetic fields suddenly and explosively rearrange themselves, converting magnetic energy into light through magnetic reconnection.

But during the solar flare event on December 10, 2013, Hinode, SDO and STEREO captured the most comprehensive observations of a current-sheet-like structure, strengthening the evidence that this understanding of solar flares is correct.

“The existence of a current sheet is crucial in all our models of solar flares,” said Dr. James McAteer of New Mexico State University in Las Cruces.

“So these observations make us much more comfortable that our models are good,” said Dr. McAteer, who is the senior author of a study on the December 2013 event, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters (arXiv.org preprint) this week.

According to scientists, a current sheet is a very fast, flat flow of electrically-charged material, defined in part by its extreme thinness compared to its length and width.

Current sheets form when two oppositely-aligned magnetic fields come in close contact, creating very high magnetic pressure. Electric current flowing through this high-pressure area is squeezed, compressing it down to a very fast and thin sheet.

This configuration of magnetic fields is unstable, meaning that the same conditions that create current sheets are also ripe for magnetic reconnection.

“Magnetic reconnection happens at the interface of oppositely-aligned magnetic fields,” said study lead author Dr. Chunming Zhu, also from New Mexico State University.

“The magnetic fields break and reconnect, leading to a transformation of the magnetic energy into heat and light, producing a solar flare.”

Because current sheets are so closely associated with magnetic reconnection, observing a current sheet in such detail backs up the idea that magnetic reconnection is the force behind solar flares.

“You have to be watching at the right time, at the right angle, with the right instruments to see a current sheet. It’s hard to get all those ducks in a row,” Dr. McAteer said.

_____

Chunming Zhu et al. Evolution of a Current Sheet in a Solar Flare. ApJL, published online April 19, 2016; arXiv:1603.07062