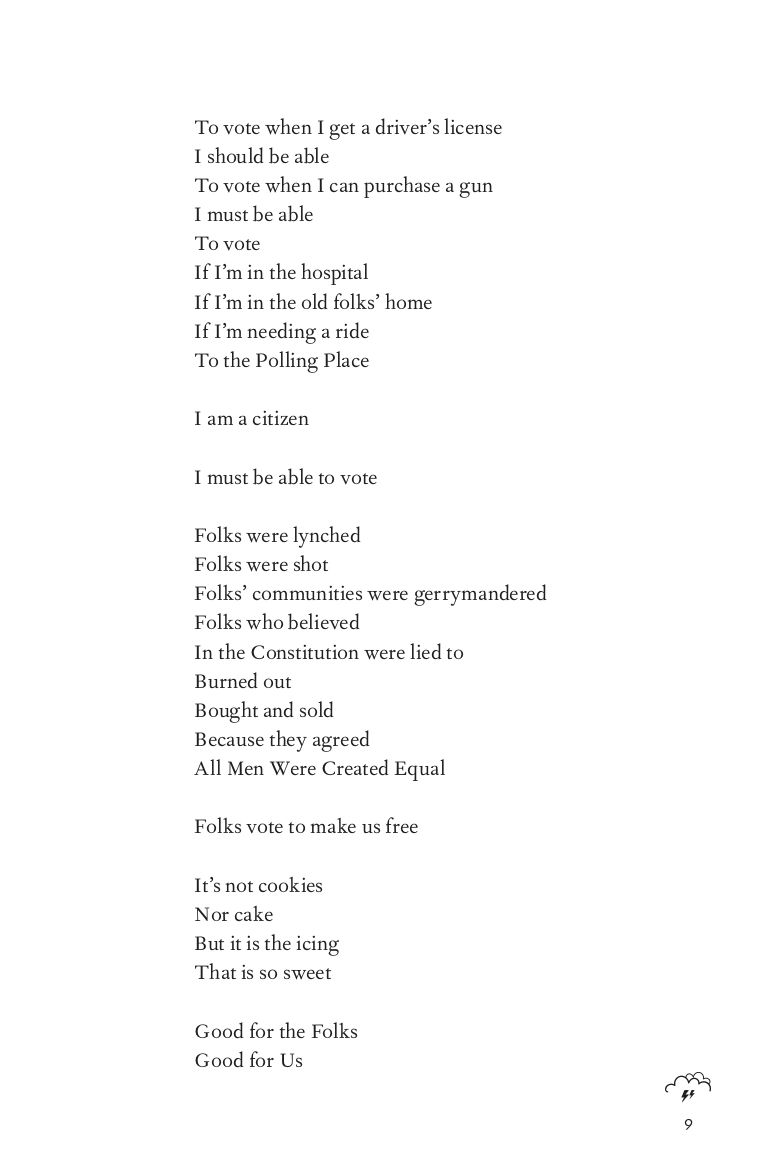

Nikki Giovanni is one of the most respected and prolific poets in the world. Venerated in the Black literary canon, Giovanni’s career spans decades and, in her latest collection, Make Me Rain, she once again dazzles her audience with timely poems that explore racism, Donald Trump, as well as intimate joy and sorrow.

Giovanni’s work has endured because she has retained a sacred imagination, that sense of unrelenting questioning. In Make Me Rain, Giovanni dreams of space, of Mars. She savors salty fried okra, the crunchy outside, the viscous pods within. With a mention of a loved one’s cold feet on our skin, she defines commitment in one stanza. “Love never goes/There is only Transition,” she writes, and anyone who has ever lost someone will shed a tear.

In her new book, Giovanni also shows us the horrific — a cop who views killing Black people as a masturbatory act. In “Kneeling is a sign of love,” she writes of the football players, like Colin Kaepernick, refusing to stand for the anthem of a country that is killing Black people like them.

Here, Shondaland chats with Giovanni about a tumultuous transfer of power after a bizarre election, the rise of white supremacy, and Black artists using their talents to define the era and themselves.

NYLAH BURTON: Your latest book talks about racism, and specifically mentions Donald Trump. How are you feeling about this election?

NIKKI GIOVANNI: I’m not surprised that Trump is trying to claim victory. But as they say, “It’s not over until the fat lady sings.” I’m gonna keep my fingers crossed because I think that Biden is a good man. I think he’d be good for the country. I think that Trump is evil and not good for the country. I’m gonna vote with the country on this one.

NB: You talk about the need for voting rights in your poem, “Vote.”

NG: Yes, and I try to be positive in the poem. But if we look historically at the so-called democracies we see they fall apart because of people like Trump — we can go back to the Greeks, to the Romans, of course, and you end up with these horrible men. I don’t know what it is because I have no respect nor need for power. When we’re watching these people do whatever they can — Putin or Trump — they’re seeking power. I can’t help but see that as cowardice.

I’m gonna hope that we recognize as we did, when we look at the numbers, Joe Biden was a hit, Clinton also won the popular vote — and we have to admit there has to be something wrong with the electoral college that people can be way ahead like that and all of a sudden they’ve lost. The people’s voice has not been heard.

Every group of people who had a republic form of government has lost it. It’s gone to an autocratic government. We may be the same. I tend to think of Trump — as I identify him this way in my mind and in my poetry — as evil. I tend to think that Trump wants to kill as many of us as Hitler did.

NB: In the poem “And So It Comes To This,” you powerfully write that the source of this hate is a sense of inferiority. How are you feeling about the rise in white supremacist violence in the U.S.?

NG: One thing that we have to do is — as the old song says — call this song exactly what it is. Trump is cowardly. So are the people who are running around with their Trump flags. We have to call them what they are, because it's not supreme. If we keep calling it white supremacy, they will think that they're supreme, but there's nothing supreme about a whole bunch of boys who are afraid.

I wish to be joined by everyone [in calling it] exactly what it is. It's cowardly. We have to talk about how these people get together in the middle of the night to try to say to somebody, "We're more important than you. We're so much more important that we're afraid to sit down next to you. We're afraid to go to the same toilet that you go to. We're afraid to sit down at the next restaurant that you do.” That's just cowardly. I think we have to call it that.

White cowardice, WC. They were very upset — they still are — that we had Black Lives Matter. You never saw the country get so upset. I was very disappointed in the white women running around going, "White Lives Matter, too."

Well, we (Black people) don't go around lynching people. We don't go around shooting white boys in the back. We don't go around shooting 14 or 15 year-old [white] boys in the back. We don't go around grabbing people out of stores, putting handcuffs on them and then pulling them out in the middle of the day, putting our foot on their neck and killing them.

It's cowardly murder. How do you sit there, how do you stand there... and watch somebody be murdered? You've got to be absolutely crazy to stand there, watching somebody put their knee on somebody, watching Mr. Floyd cry out to his mother who has passed. He's crying out to his mother in heaven, crying, "I can't breathe."

Then the police get angry when people say, "We're sick of you, and we don't want that." They say, "We're here to protect you." No, if that's protection, I don't need it.

NB: How was the experience of weaving joy and pain throughout this book to create something beautiful?

NG: Oh, well, thank you. It's wonderful that no matter what else is happening, we still have found a way to have a song. We found a way to make our souls let us be rich within ourselves. I wrote a line a long time ago, I believe it says, "Black love is Black wealth." I think that's what's great about Black Americans.

NB: I'm really glad that you brought up that line, "Black Love is Black Wealth." It comes from the poem, "Nikki-Rosa." When I told my friend that I was interviewing you, he said, "I just really want you to tell her that ‘Nikki-Rosa’ was a wonderful poem that made me reevaluate my childhood in ways that greatly contributed to my growth." That's one of your most beloved poems. What does it mean to you?

NG: When I wrote it, I had to make some decisions about myself. We all have to make decisions about who we are. It's fair to say that my parents had a difficult marriage. Hearing their arguments, hearing the kinds of things that parents do, that was upsetting. I had to decide what was important here. I realized, of course — I was, I don't know, 15, 16 years old — that the most important part of my life was me. I could say that to anybody, "You are the first person in your life.” I decided well, if that's the case, then I don't want my life to be defined by other people.

[In college], if you're reading essays or you're reading novels, every time you talk about the Black community, it's always something sad. I thought, "No, wait a minute. Now there has to be something good. There has to be some joy. Because if there wasn't, we couldn't have made it. How do we come through 300 years?"

I'm a big space fan. Spock would say, "It's illogical, Captain." And so it would be. That meant that in some place, I was happy. My family didn't have much, but what did we have? Despite the difficulty of my parents' marriage, we both — I had an older sister [Gary-Ann] who has passed now — knew that Black love was Black wealth. We always felt very special. "Nikki-Rosa" just came together when I thought, "I'm going to define myself and what's important."

NB: Your poem "Transitions" echo pain and joy. How have those transitions of love shaped you as a poet?

NG: If I can, I think all poets are always in love. It's probably the two things poets do and love doing — we fall in love and we like to cook. The combination really begins some work. I think that we do transition. Some transitions would be called death, other transitions would be called growing up. You mentioned earlier that you're 25. That's a good age. I'm 77, so I'm 52 years older than you are. I want you to be 77 because when you get to be 77, you are going to have transitioned. You're going to change the way you think about a lot of things. One of the things you're going to do is you're going to learn a lot about love.

You're gonna learn that love has nothing to do, of course, with sex. Sex has its place, it's a lot of fun. But eventually, you're going to find out that love has to do with that commitment. Someone you love is ill and you have to be there to wipe his face. Or he's diabetic, you're going to want to make sure that he gets shots. That's love. Being there when somebody needs you to be there.

NB: You once said that you highly recommend old age because it's really fun. What is really fun to you about your age right now, where you are in your life right now?

NG: Well, it's really fun because I am, if I may, confident that I've done what I should do. I was very close to my grandmother. I'm sitting here at my desk right now. I think if Grandmother came to the door, I could say to her, "I did my job." If she had asked me 50 years ago, I would say, "I'm working at it." But now I can relax.

One of the things about being old, if I may, is that you're happy. You're looking at your life and you're saying, "I am satisfied that I've done the job. I didn't cheat on myself.”

NB: Why do you like space so much? And Mars?

NG: I shared a bedroom with my older sister. Gary liked the wall. I ended up on the other side of the room with the window, because we only had the one window. I was always looking out at the stars. I would think, there has to be some logic, some life. It's illogical that there would not be life. Then I would start to try to figure out, where is Mars? Where's the North Star? In this galaxy, where is the life?

I don't want to just be negative. But when I look at our galaxy, the one in which Earth and Mars are, I think, "Well, what a mistake. There has to be something else, because if this is it for life, then somebody made a mistake."

NB: Another thing I do want to ask you is: what are you cooking right now? In your book, you talk about so much good food. It made me hungry.

NG: I'm making my grandmother’s oxtails, but with veal, putting lots of things in and seeing how it is. I get teased about that from a lot of people. The reason I think I like stews and quilts is that I live in America. America is a stew. It is a lot of different things that come together. If we're lucky, it makes for a good meal. It's the same with a quilt. We keep putting pieces together, no matter what anybody says, like, "We don't want these people here." We want everybody here because it's all a part of the quilt that makes us a strong or stronger nation.

Nylah Burton is a Washington D.C. based writer. Follow her on Twitter @yumcoconutmilk.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY