The Hunter S. Thompson You Don't Know

The author is remembered more for his persona than for his writing—which is a shame

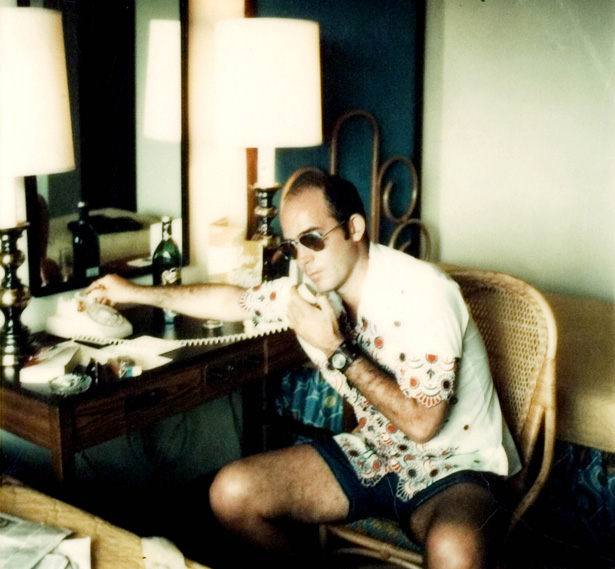

AP Images

If you talk to people who knew Hunter S. Thompson, born 74 years ago this week, you are going to hear crazy stories. From Thompson's birth, boyhood, and schooling in Louisville, Kentucky, to a brief stint with the Air Force, even briefer stints with several newspapers and magazines in the early 1960s, the 1966 publication of his first book, Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, until his death by a long-promised suicide in 2005, the author, journalist, and all-American antihero cut a broad swath through life, becoming as infamous for a love of drink, drugs, and guns, as he was famous for his literary career.

That's a shame. Hunter's antics as the woozy, half-mad, cosmic prankster in a golf hat, shooting glasses, and a gaudy print shirt too often can obscure a less-exciting, but perhaps more significant aspect of his character: Thompson as a writer at work.

Hunter indulged for all the typically human reasons, ranging from an authentic quest for new experience to simply bludgeoning demons into submission. Lord knows that drug-addled lunacy was essential Thompson's life and art, just as it was to William Burroughs, Baudelaire, Byron, and Shelly.

Hunter was perhaps unique because drink-and-drug-fueled madness weren't only his subject matter and milieu—they were his cause célèbre. As the most articulate, and most militant advocate of the better-living-through-chemistry ethos to arise in the counterculture movements 1960s, Thompson saw mind-altering chemicals, particularly high-powered hallucinogenics, as weapons in the culture wars. This was a man, after all, who ran for the Sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, on a platform of Freak Power, using the campaign poster designed by Tom W. Benton depicting a fist with two thumbs clenching a button of peyote.

But Hunter did more than get blasted and do crazy stuff. That would make him no different from half of humanity. He also didn't merely get blasted, do crazy stuff, and write a bit about it. That would make him Neal Cassady. Thompson wrote a lot, on a panoramic array of subjects, with dazzling technical proficiency, plus passion, wit, fury, sensitivity, reams of jaw-dropping sensory detail, and a fanatical devotion to the English language roughly akin to what Torquemada felt for the pope.

Curtis Robinson, a former editor of the Aspen Daily News, was a Thompson collaborator for a decade, and has all the requisite tales Thompson-led madness. Yet Robinson paints a picture of the author far different from the well-known trickster/prophet persona.

"Most of my time with Hunter," he said, "we were in late-night work mode."

In a Kentucky drawl and muddled cadence eerily akin to his mentor's voice, Robinson described how hard Thompson worked to make his writing look easy, stressing the endless hours spent at the typewriter, struggling to craft his prose.

"There was this time he was needed a word, a synonym for 'posh,' but with some slightly different meaning," Robinson said. "He tried to find it for 18 straight hours."

"He liked to have people read out loud," Robinson continued. "I could be reading something he had written 20 or 30 years ago, but he would know it so well that if I accidentally skipped a word—even a short one, like an 'and' or 'the,' he would immediately catch it and stop me. That's just how attuned he was to the work, and his own rhythms."

Of course, the guy did manage to get out of the house once in a while.

One of those trips, ostensibly taken to report on a race in the Nevada desert, turned into an epic of creative destruction—a mix of radical political theater, raw debasement, elegant debauchery in the Southern Gothic style, and monkey-wrenching vandalism.

Translated into a Roman à clef, that trip became what Thompson dismissively called "the Vegas book," but the rest of the world would know as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.

Before Vegas, Hunter's patented brand of Gonzo Journalism—the deeply personal, ferociously hallucinogenic style he created in 1969 with "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved"—was still just a sub-genre of New Journalism. The experimental school born in the 1960s called for journalists to surrender the pretense of objectivity and inject their own experiences into stories, often by using techniques more commonly found in novels, short stories, poetry or plays. Before "the Vegas book," Hunter was on a short list of New Journalism's leading lights—along with Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, George Plimpton, Gay Talese, and perhaps a dozen more.

When Vegas was published—first in November 1971 as a story in Rolling Stone magazine, and in book form the following year—all that changed. From the stark blast of its opening line—a sentence that would soon join "Call me Ishmael," and "It is a truth universally acknowledged," among the more memorable opening lines in literature—all the way to the famed coda in which Thompson's protagonist and alter ego, Raoul Duke delivers a venomous, yet truly mournful eulogy for the dead dreams of the utopian 1960's, the reader barely gets chance to breathe. Vulgar and charming, obscene and honest, with a seemingly unquenchable rage, and unending list of things to rage against—the pain of the human condition, the various betrayals he sees of the American Dream, or the horrors of Debbie Reynolds in a silver Afro wig.

For a follow-up, he out did himself. By a longshot. He covered the 1972 presidential election in Rolling Stone, work collected and published as the intimidatingly thick tome Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail '72. Though Vegas might be his best-known work, Campaign is far more important.

Thompson didn't just break the long-standing agreement between politicos and press to keep "minor" scandals from the public eye. (Cough, John Edwards, cough.) He tore it up and burned the pieces, gleefully exposing lies wherever he saw them and denouncing hypocrisy with an apocalyptic vengeance, using language that makes today's supposedly outrageous media pundits look like Disney characters.

Campaign Trail was equally ruthless, and equally groundbreaking, for being first to give the American people a glimpse at the inner-workings of the noble Fourth Estate—i.e. exposing the often equally shocking hypocrisy, and all-around depravity, of the press corps.

After Campaign Trail, Hunter was a genre unto himself. Gonzo had evolved from a mere writing style into comprehensive worldview. It not only encompassed a literary and visual aesthetic—the latter created with the help of long-time Thompson illustrator Ralph Steadman—but also a political ideology, an ethical code. The depth to which Thompson's sensibility and persona has permeated American mass consciousness is simply staggering. He wasn't a rock musician or a movie star, and he famously hated appearing on television. Yet he ended up as the model for the "Uncle Duke" character in the Doonesbury comic strip, for Spider Jerusalem, protagonist of the DC Comic Transmetropolitan, and for Hunter Gathers on Adult Swim's The Venture Bros, among others. Gonzo, Thompson's watchword and brainchild, even gave its name to a Muppet. He was played on film by Bill Murray—in a well-meaning but ultimately icky biopic, Where the Buffalo Roam. (Truth be told, Murray was basically doing a Hunter impression playing Carl Spackler in Caddyshack.)

Thompson was played to much greater effect by Johnny Depp, first in Terry Gilliam's fine film adaptation of Vegas, and recently in the animated feature Rango, in which Depp voices a very Thompson-like lizard. In fact, it is Depp—not Bill Murray, or Garry Trudeau—who finally portrayed Hunter's persona as a fully-developed character, rather than mere caricature. For all of Hunter's powerful literary advocates and acolytes, it was Depp who brought Thompson's work to a mainstream international audience. And it was Depp, a fellow Kentuckian, and follower of the decadent Southern tradition, and another admirer of French symbolist poets, whose friendship seemed to somehow ease Hunter into his Literary Lion-in-Winterhood. Ironically or not, it was Depp—a movie star—whose self-identification as Hunter's spiritual progeny seemed to satisfy Thompson more than having three whole generations of writers be so deeply influenced by his style and spirit.

This fall, 11/11/11, will mark 40 years since the first appearance of Fear and Loathing, and the flow of new works by, about, or tangentially related to, Hunter S. Thompson shows no signs of stopping. A new coffee table book about Tom Benton was just released, filled with glossy reproductions of vintage Freak Power art work. Depp just completed shooting on another film version of a Thompson book: The Rum Diary, which follows the Hunter-esque escapades of an American journalist in Puerto Rico, comes out this fall. As does Gonzo Republic: Hunter S. Thompson's America by William Stephenson, which purports to be the first serious academic study of Thompson's work in over two decades. In 2012, as part of the build-up to Hunter's 75th birthday celebration next summer, we will see the release of the third and final volume of Thompson's collected letters, edited by historian and Hunter homeboy Douglas Brinkley.

Curtis Robinson, who just signed on to cover the upcoming primaries for a new political website, Big Gonzo, says Hunter's letters are gems, "Written when people took letters seriously, by a man who was serious about his letters."

There are even a few pranksters trying to get a statue of Hunter installed on the Las Vegas Strip —a sculpture that would depict the Good Doctor aiming a shotgun at his typewriter. Which is... fine. But, though far fewer folks would see it, it might be more fitting to put that statue elsewhere. Like, say, back at Thompson's beloved Owl Farm in Woody Creek, Colorado. Also, even if the effect won't be as exciting, perhaps instead of shooting a typewriter—which he might have done fewer than a half-dozen times over nearly seven decades on the planet, that statue could show Hunter doing something he did virtually every day of his life, for hours on end—something much, much harder than shooting a typewriter: writing with it.