The Story Behind Eugene O'Neill's Lost Play, 'Exorcism'

His 1919 one-act about his own suicide attempt is being published in book form for the first time this week.

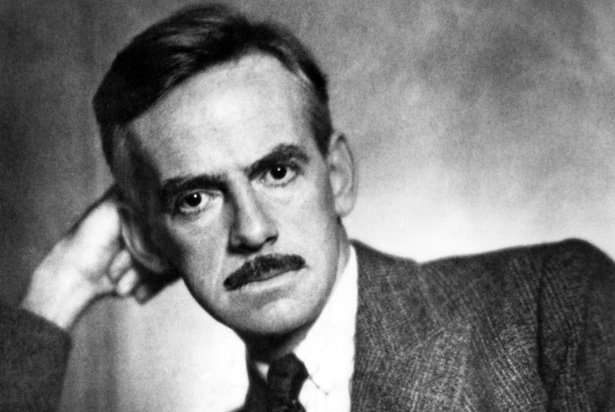

AP Images

There's a lot that one could say, and that has been said, about Eugene O'Neill's "lost play" Exorcism, published in book form for the first time this week. Some debate O'Neill's motives for pulling the play—which he wrote in 1919, before he gained fame for works like The Iceman Cometh and A Moon for the Misbegotten—and destroying the copies. Others wonder if the play should have stayed "lost," as per the author's wishes. But the most remarkable aspect of the play isn't that it was pulled or that it has subsequently been published—it isn't even that it depicts the author's own suicide attempt. The most remarkable aspect is that it was ever lost—and found—at all.

Neither Yale University Press, which publishes the first edition of the play this week, nor The New Yorker, which ran the play in a magazine issue after its rediscovery last fall, have much reason to feel guilty about not respecting the author's wishes. Just think of the works humanity would have missed if writers and artists were allowed complete rights to self-censorship. Virgil wanted the Aeneid burned. Kafka's most famous works were unpublished at the time of his death—that we know them now is due only to his friend Max Brod's defiance of Kafka's wish that they be destroyed. Felix Mendelssohn discarded his Reformation Symphony, regarding it as an inferior work and refusing to allow its publication during his lifetime.

Even with Exorcism, specifically, there's little cause to regret the play's rediscovery. "Should Eugene O'Neill's lost play have stayed lost?" asked a headline on The Guardian's theatre blog last October. Frankly, no. There are two arguments currently on offer for why The New Yorker or Yale should have, as the post's summary suggests, "respected [O'Neill's] wishes." The first is that the subject matter was a bit personal. The second is that the play isn't particularly good. Here's the problem: If you want to publish or not publish O'Neill's plays according to these criteria, you'll have to be willing to censor a few more works along with Exorcism.

MORE ON BOOKS

True, the play is quite personal: The one-act story recounts O'Neill's own attempt at suicide, foiled by a friend who himself committed suicide not long thereafter. The New Yorker's theatre critic John Lahr, introducing the text last October, suggested that the author pulled the play out of sensitivity to his father, who had recently suffered a stroke.

But really, now. The play's hardly more embarrassing either to the author or to his late family than A Long Day's Journey Into Night, which deals not just with O'Neill's own demons ("I would have been much more successful as a sea gull or a fish," declares the O'Neill character—how's that for vulnerability?) but also with his father's stinginess, his mother's drug addiction, and his brother's love of booze and brothels—the last a feature of A Moon for the Misbegotten as well. O'Neill, understandably, wanted A Long Day's Journey held till 25 years after his death, although in fact it was published only three years after his passing. Applying the 25-year rule here, Exorcism is well past its allowable publishing date.

What about Exorcism's dramatic clumsiness? The play "is not a very important milestone in [O'Neill's development as an artist," American playwright Edward Albee notes in his sensitive if discriminating forward to Yale's edition, "and I suspect his drive to do away with it has less to do with its subject [...] than it does with his dissatisfaction with the play's structure and resolution—especially the fact of the play's anti-dramatic second and final scene, which takes the play nowhere and has little to do with dramatic logic."

This, in fact, is the point of the Guardian Theatre Blog post as well. The author, American literature professor Sarah Churchwell, concludes that "Exorcism reads like what it was: the last apprentice-work of a playwright who was just six months away from coming into his own as an artist, with Anna Christie and The Emperor Jones both premiering a few months later." Should O'Neill have been afforded the privacy Albee, too, notes most artists have at the beginning—to "commit student work," "pre-opus" material prior to one's début with a piece finally judged "good enough to list it among the pieces I'm willing to take credit for"?

Of course, O'Neill did allow Exorcism's performance before changing his mind—it was staged by the Provincetown Players in 1920. And as for the play's amateurish structure, Churchwell provides a rebuttal in her own post: A lot of O'Neill's works look a bit of a mess on the page. Churchwell even goes so far as to call him "America's worst great writer," pointing out that "he sometimes seems to hate the language with which he works."

She has a point here. In fact, Exorcism held my attention with greater ease than I was expecting. The sparser stage directions suggest a more confident, less micromanaging author than that of Beyond the Horizon, also appearing in 1920. That play won a Pulitzer Prize, but the italic-heavy lines read like something written for marionettes. Exorcism also, perhaps due to its one-act form, has a lot more movement than Long Day's Journey, in which a staggering ten lines in the first five minutes are dedicated, by various characters, to telling the character Mary some variant of how nice it is to see her "fat" again. "Fat" is a stand-in for "healthy," and the audience is meant to realize that Mary has not been well. The audience (and certainly the reader) probably got this after the second line to this effect—after ten, O'Neill might as well have written in a flashback where the characters come out into the seats and bash a few viewers over the head with Mary's senseless body.

What do we gain by Exorcism's publication? On a purely textual level, pretty much exactly what we gain from the publication of any of O'Neill's plays: another window into an artist's soul; a better understanding, subsequently, of his development; and a few observations and images to take home and ponder as we go about our own lives.

What sets Exorcism aside is its story—not the story told in the text, but the story of the text's own survival. After the play was performed, O'Neill had a change of heart, and he recalled and destroyed the scripts. He clearly missed, whether intentionally or unintentionally, the copy spirited away by his later much-hated ex-wife, Agnes Boulton, but the play nevertheless vanished for over 90 years. Would a playwright bent on destruction today have half a good a chance of making his work disappear for this long?

The tale of the play's resurfacing is still more dramatic. According to Louise Bernard, a Yale library curator who pens an introduction to the text in the new edition, Agnes Boulton appears to have given Exorcism quietly to screenwriter Philip Yordan in the 1940s, enclosed in an envelope with Christmas stickers and the label "something you said you'd like to have." This is in stark contrast to the picture we get of the scorned ex-wife in O'Neill's own writings, where Boulton is accused of having stolen a diary and sold it. Neither the diary nor Exorcism, Bernard points out, were ever sold. Exorcism, once in Yordan's possession, doesn't appear to have raised much fuss. It was only recently discovered by his widow, sorting through his papers after his death in 2003.

This is a history worth its own creative rendering. What secret motivations, disputes, and anti-climaxes lie behind the clues Bernard has culled from the archives? Exorcism's most enduring message may be that, even with artists, the drama on stage is no less real than that of everyday life. And even when art is being drawn from experience, the most compelling scenes often take place in the wings.