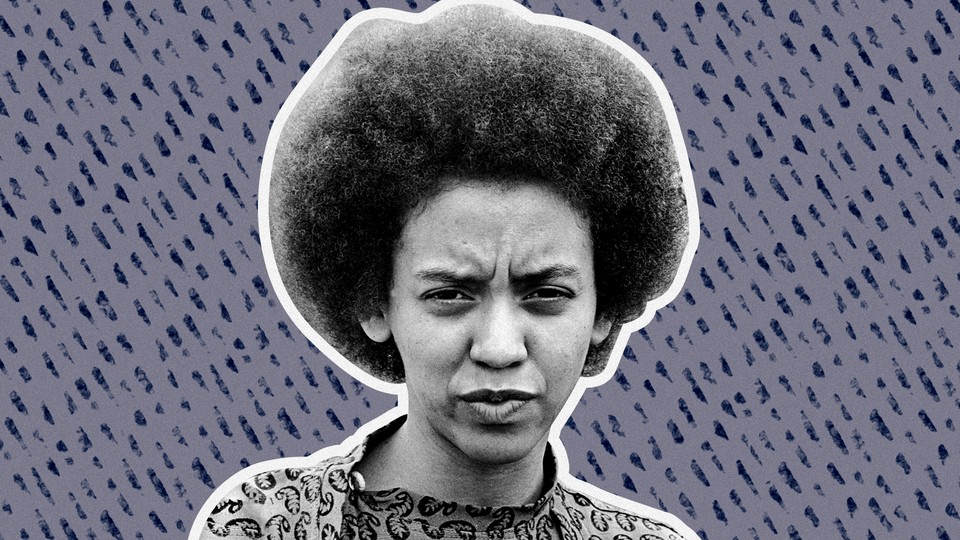

Nikki Giovanni: 'Martin Had Faith in the People'

The day after King’s death, the writer-activist wrote a poem about what his loss meant to a movement. Fifty years later, she discusses how his model of leadership lives on.

The day after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Nikki Giovanni—the brilliant young writer who’d soon come to be known as the “Princess of Black Poetry”—wrote a poem that began with an inquiry: “What can I, a poor Black woman, do to destroy america?”

For Giovanni, the question was a collective one that was “being asked in every Black heart.” And it wasn’t at all rhetorical: “There is one answer—I can kill,” she continued. King’s assassination was “an act of war,” Giovanni surmised, that would at last spark black rebellion. “May the warriors in the streets go ever forth into the stores for guns and TV’s, for whatever makes them happy (for only a happy people make successful revolution) and this day begin the Black Revolution,” she wrote.

It would be easy to dismiss Giovanni’s call for looting and armed revolt as the knee-jerk reaction of an enraged and wounded 24-year-old artist. Yet the poem, called “Reflections on April 4, 1968” (its title alone suggesting cool meditation rather than impassioned response), now appears to offer a surprisingly durable theory of history. That theory has shaped Giovanni’s public persona for the past 50 years, and while its militant thrust can obscure this point, it also shaped King’s own.

By titling “Reflections” with a date instead of naming King’s death, Giovanni anticipates how “April 4, 1968” will become synonymous with that world-historical loss. But she also implies a more expansive view of what happened that day, one that is less about King’s death than about how black Americans responded to it: They were already rioting in cities across the country by the time Giovanni sat down to write and reflect. Rather than memorialize King’s leadership, Giovanni turns to the people he seemed to be leading, and asks what they might do, in his absence, to subvert or fulfill his legacy.

By focusing on King’s impact on “poor Black [women]” and on other everyday people, Giovanni honors King’s own populist ethos. That ethos comes through in King’s sermonic technique of ending his speeches with lyrics that his listeners might sing together. He sometimes transposed those lyrics into communal terms. At the 1963 March on Washington, for instance, King imagined a multiethnic group of citizens joining hands to sing, “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty we are free at last.” Giovanni pays unexpected homage to that technique when, at the end of “Reflections,” she alludes to King’s favorite gospel song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” and turns its petition for individual aid (“Take my hand, lead me on”) into a call for collective action: “Precious Lord—Take Our Hands—Lead Us On.”

Now 74, Giovanni has remained both a true renegade and a steadfast, beloved poet of the people for the same reason that King became a great leader: their belief in ordinary folk and willingness to work both with them and for them. For King, that meant boycotting segregated buses, investing in black-owned banks, and supporting striking sanitation workers. For Giovanni, it has meant, in addition to writing poetry, recording spoken-word albums in the ’70s and delivering a unifying convocation speech at Virginia Tech (where she’s now a professor) after the 2007 mass shooting there.

In a recent interview with The Atlantic, Giovanni explained that her populist ideals are in line with King’s belief in collective leadership—in empowering regular individuals to be at the fore of the struggle for civil rights. “I have a lot of faith in the people,” Giovanni told me. “‘Cause if we don’t have faith in the people, then how are we going to go forward? But Martin had faith in the people. You’re standing there on the [National] Mall, speaking to the people because you believe in them,” she said, referring to King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Giovanni insists that the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson should be recognized as the person who prompted King to “tell them about the dream.” It was at Jackson’s urging, Giovanni notes, that King told the crowd, in essence, “I have faith in you. I think that we can go forward. We who are black, white, men, women, straight, gay … That’s what his dream really meant.”

People responded to King’s calls for peaceful protest not because they imagined they were invincible, Giovanni said, but because they knew they were imperiled. “It was a dangerous time,” the poet recalled of the ’50s and’60s, especially for black Americans. “You woke up everyday being surprised that you were alive.” She noted the spate of assassinations of high-profile civil-rights figures that took place over the course of just five years: Medgar Evers and John F. Kennedy in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, and Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy in 1968. “We put our lives on the line, because we knew our lives were always on the line,” Giovanni said of civil-rights activists. “You couldn’t be black in that era and not think they were going to lynch you. The death of Emmett Till [in 1955]—he was only 14—said that to all of us.”

Because Mamie Till, Emmett’s mother, demanded that others see her son’s brutalized body, Giovanni sees her as one of the many unsung heroes of the movement. “We don’t celebrate [her] the way we should,” Giovanni said. “What would have happened if she had let him be buried in a closed casket? But she opened the casket to let the world see him. And you looked at Emmett Till and you thought, we can’t let this happen.” Giovanni named other martyrs of the civil-rights cause whose memories are worth “summoning” today: Evers, the field secretary for the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP who died after being shot in his driveway; and Viola Liuzzo, a white woman who was shot two years later after having assisted activists marching from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. “Martin was leading the pack,” Giovanni said. “But a lot of brave people did a lot to make a difference.”

Giovanni’s 2002 poem, “In the Spirit of Martin” (which takes its title from a Smithsonian exhibition of the same name), summons several such figures. The work is a tribute to King, whom Giovanni calls “the voice of his people.” It is also, the poem spells out, “a Thank You to Diane Nash … a flag for James Farmer … a HowCanIMakeItWithoutYou to Ella Baker.” Finally, like “Reflections on April 4, 1968,” the work is a paean to countless anonymous men and women:

black men of vision … black men of hope …

bent over cotton … or sweet potatoes … or pool tables and

baseball diamonds … playing for a chance to live free and

breathe easy and have enough money to take care of

the folks they love

In a sense, Giovanni’s poetry anticipates more recent works that forego hagiographic portrayals of King’s singular leadership to offer more communal accounts of the movement—including Danielle McGuire’s 2010 woman-centered history At the Dark End of the Street and Ava DuVernay’s 2014 biopic Selma. Yet Giovanni also invites her readers to see how King himself shared that ethos; her collective vision is itself “in the spirit of Martin.”

The fact that this model of decentralized leadership lives on today gives Giovanni hope for the future. “There’s a new world out here,” she said. “And I’m in favor of the new world. I’m in favor of the kids”—including Black Lives Matter activists and students from Parkland, Florida, now pushing for gun control in their state and beyond. The sense that “people keep murdering you and nobody will do or even say anything about it … would make you as nervous to be going off to high school now as it was for us in those days to be going off to a march,” Giovanni said. “But young people today are beginning to say, ‘Something is wrong with this planet.’”

It is because people drive such movements for racial justice and public safety, partly by selecting and granting legitimacy to their leaders, that those movements might continue once their leaders are gone. Hence, in a 1968 work titled, simply, “My Poem,” Giovanni contends that the movement for black liberation will outlive her: “if i never write / another poem / or short story” or “do a meaningful / black thing / it won’t stop / the revolution.” Even, she writes, “if they kill me / it won’t stop / the revolution.”

This is precisely the declaration King made in Memphis, on the eve of his death: “I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land,” he assured his listeners. Then, as was typical, he led them in song.