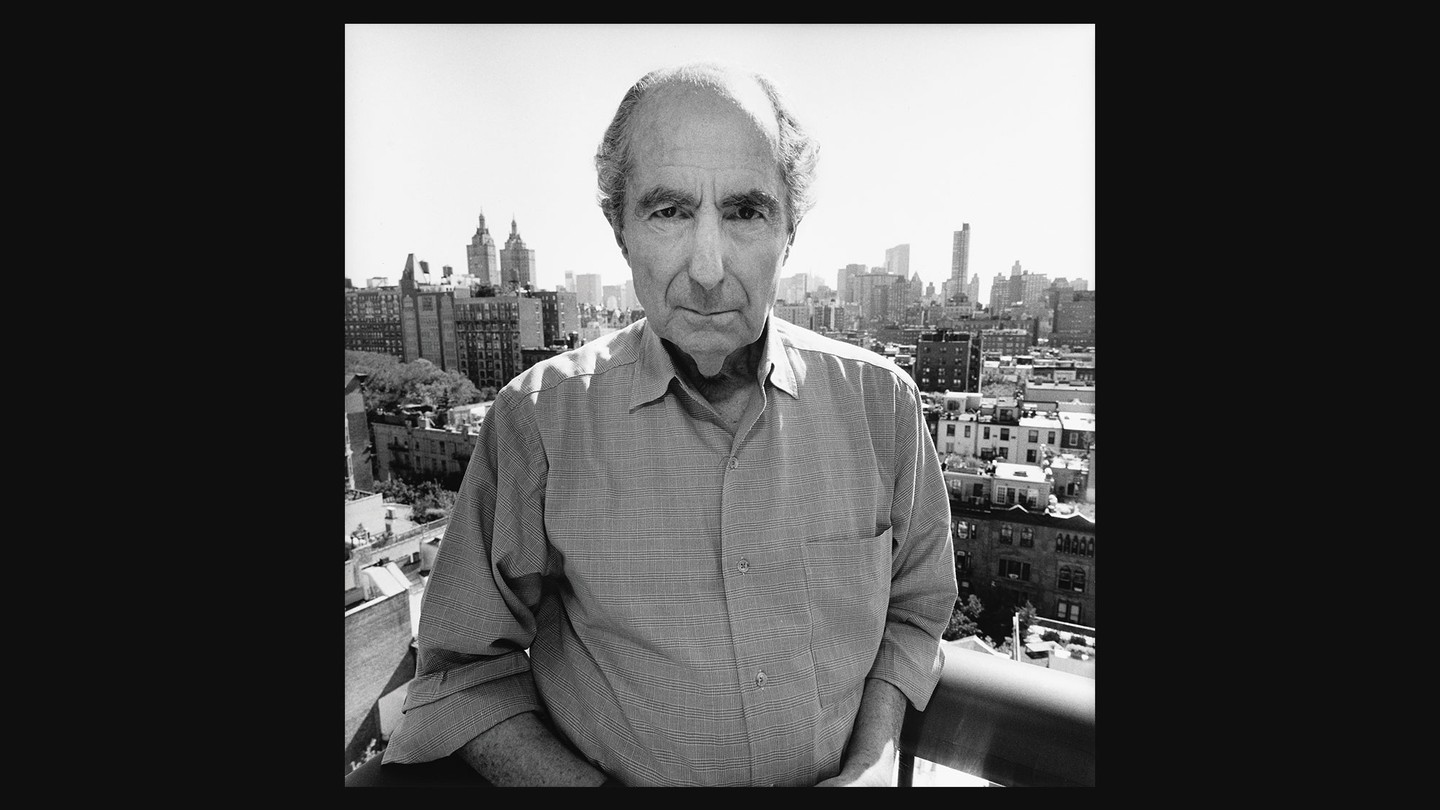

Philip Roth’s Terrible Gift of Intimacy

During his last two decades, we spent thousands of hours in each other’s company. It was a little like a marriage; I couldn’t have done without it.

Updated at 12:03 p.m. ET on April 26, 2020.

Delirious near the end, he said, “We’re going to the Savoy!”—surely the jauntiest dying words on record. But it was Riverside Memorial Chapel, the Jewish funeral parlor at Amsterdam and 76th, that we were bound for. I was obliged to reidentify the body once we arrived there from New York–Presbyterian Hospital. An undertaker pointed the way to the viewing room and said, “You may stay for as long as you like. But do not touch him.” Duly draped, Philip looked serene on his plinth—like a Roman emperor, one of the good ones. I pulled up a chair and managed to say, “Here we are.” Here we are at the promised end. A phrase from The Human Stain came to me: “the dignity of an elderly gentleman free from desire who behaves correctly.” I wanted to tell him that he was doing fine, that he was a champ at being dead, bringing to it all the professionalism he’d brought to previous tasks.

To talk daily with someone of such gifts had been a salvation. There was no dramatic arc to our life together. It was not like a marriage, still less like a love affair. It was as plotless as friendship ought to be. We spent thousands of hours in each other’s company. I’m not who I would have been without him. “We’ve laughed so hard,” he said to me some years ago. “Maybe write a book about our friendship.”

Our conversation was about everything—novels, politics, families, dreams, sex, baseball, food, ex-friends, ex-lovers. Philip’s inner life was gargantuan. Insatiable emotional appetites—for rage as for love—led him down paths where he seethed with loathing or desire. “There’s too much of you, Philip. All your emotions are outsize,” I once said to him. “I’ve written in order not to die of them,” he replied.

But our keynote was American history, for which Philip was ravenous, consuming one big scholarly book after another. He became a great writer over the course of the 1980s and especially the ’90s, when his novels became history-haunted. In the American trilogy—American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain—the heroes, Swede Levov, Ira Ringold, and Coleman Silk, are solid men torn to pieces when the blindsiding force of history comes to call. Such was Philip’s mature theme: the unpredictable brutalities at large in the world and the illusoriness of ever being safe from them. He never stopped marveling at how contingently a fate is made. For him, that was most basic to storytelling: the happenstance that in retrospect turns epic.

I’d been taking notes all along. A lot of conversation got squirreled away. “Memories of the past,” he wrote in The Facts, “are not memories of facts but memories of your imaginings of the facts.” Though imagination in memoir may indeed be inevitable, I have tried at every turn to bar the way. As a novelist, he believed that the truth was composed of perspectives and partial understandings. “Getting people right is not what living is all about anyway,” he wrote in American Pastoral. “It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.”

Yet he was not similarly skeptical about his own self-understanding in real life—“the unwritten world,” as he preferred to call it. “We judge the author of a novel by how well he or she tells the story,” Philip wrote, again in The Facts. “But we judge morally the author of an autobiography, whose governing motive is primarily ethical as against aesthetic.” Then we want to know: “Is the author hiding his or her motives … telling in order not to tell?” All I can say is, I am trying for candor here.

One day I described for Philip a strange case I’d been reading about. A man named Thomas Beer, who was Stephen Crane’s first biographer, wove a tissue of creative lies, inventing loves and friendships that never were, even concocting virtuoso letters from Crane. His 1923 book was fiction posing as fact. A succession of Crane scholars went charging down Beer’s blind alleys.

“May his bad example haunt you,” Philip said.

He was genuinely puzzled by gossips. “All the fun of a secret is in keeping it. Why blab?” Maybe he took this view because he’d been more victimized by gossip than other people have been. He was oversensitive, and sometimes mistook genuine concern for idle chatter. One mutual friend particularly drew fire for talking to anyone who’d listen about a recent operation that Philip had undergone. Orthopedic surgeries could be openly reported, in Philip’s view, but cardiac procedures were confidential. “Can you imagine? He told five more people after I told him to stop. All of whom called this afternoon.” In our friend’s defense, I said his gossiping was like a locomotive and could stop only gradually.

Secrets and deceptions of every kind, though, appealed to Philip. He was not averse to cuckolding inattentive husbands. More wholesome opportunities for subterfuge were catnip too. Some years ago, when I was submitting for publication a novel I’d written, he suggested that I employ a pseudonym. We settled on Shoshana Lipshitz, a winner by the sound of the curriculum vitae we concocted: four years at Hotchkiss, women’s studies and astronomy at Harvard, an internship at The Paris Review, Romance languages, European wanderings, the whole bit. We decided she was very pretty, a Natalie Portman type. To top it off, I proposed an archaeological year in Mesoamerica, but Philip said we were getting carried away. “Maybe publishers won’t like being fooled like this,” I said. “They know how to Google.” For our part, we Googled what turned out to be a small army of Shoshana Lipshitzes, variously active in the world. Our ruse, which would have been doomed to quick exposure had we launched it, died at birth.

Although he was my best friend and I his, there were rooms in the fortress of secrets marked “P. Roth” that I know I was excluded from. This went both ways, but he was an incomparable student of inner lives, of what’s invisibly afoot. He managed to figure out more about me than I ever could about him. In The Ghost Writer, the narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, says of the novelist Felix Abravanel that the master’s charm was “a moat so oceanic that you could not even see the great turreted and buttressed thing it had been dug to protect.” Philip, too, could seem a beguiling but remote citadel: august, many-towered, lavishly defended. Those who reached the inner keep met someone quite different from the persona devised for public purposes. Still vitally present at home was the young man he’d remained all along, full of satirical hijinks and gleeful ventriloquisms and antic fun.

We weren’t equals, of course, and not just because he was 20 years older. Sometimes I thought of him as the chosen parent of my middle age. His love acted on me, as on everyone, like a truth serum. He possessed the terrible gift of intimacy. He caused people to tell him things they told no one else. His mineral-hard stare was impossible to hide from.

“Something’s not right with you. Don’t bother saying you’re okay, because you’re not. Just say what’s going on.”

I told him it was bleakness. The shine had gone out of everything. Strangulation in the viscera; no food seemed edible. Once or twice, to my shame, I’d gone to bed hoping a heart attack would finish me. In a word, I was ill.

Here was the sort of assignment Philip reveled in. He got me to his psychiatrist within 24 hours. “Tell him exactly what you told me. He’ll fix you up. Don’t tell him about how Mama burned the roast in ’57 and Daddy got so mad. He’s not that kind of doctor.” I had thought anxiety and depression were mutually exclusive. Our doctor told me they go together like Rogers and Astaire. He fixed me up with sertraline and olanzapine and may have saved my life. But the drugs have made me tearless. An odd side effect. At Riverside Chapel, seated beside the dead man I adored, I found I could not cry.

I can’t be the first gay man to have been an older straight man’s mainstay. Philip had searched diligently for a beautiful young woman to see to him as Jane Eyre looked after old Mr. Rochester. What he got instead was me. The degree of attachment surprised us both. Were we lovers? Obviously not. Were we in love? Not exactly. But ours was a conversation neither could have done without. Twelve years ago I saw him through his last love, for a young person less than half his age whose family strongly disapproved of the association and who evidently grew to disapprove of it herself. It was a trauma that might have plowed Philip under and that he told aslant in Exit Ghost, the novel dedicated to me. A couple of misguided attempts at courtship followed, painful for the women involved. Then he closed the door on erotic life entirely. He’d learned how to be an elderly gentleman who behaves correctly. He joined the ranks of the sexually abdicated.

I said: “I think I’ve worshipped at the altar of Eros long enough. I think my dues are paid.”

“Wait ’til you go well and truly to sleep where the body forks,” he said. “A great peacefulness, yes. But it’s the harbinger of night. You’re left to browse back through the enticements and satisfactions and agonies that were your former vitality—when you were strong in the sexual magic.” The peace was hard-won. “First my vehement youth, all fight and craving,” he told me. “Then this so suddenly—old age telling me to have a long last look. I’ve come through. I’m on the other side of all battles. Aspiration, that beast, has died in me. Whenever death comes to mind, I tell myself, It is now and here we are, and this suffices. So long as we’re alive, we’re immortal, no?”

Why was the public so exceptionally interested in his personal life? E. L. Doctorow inspired no such curiosity. Neither has Alice Munro nor Toni Morrison nor Cormac McCarthy. Gossip about Cynthia Ozick is hard to come by. About Don DeLillo, it is nil. Philip was something else altogether. True, J. D. Salinger comes to mind, chiefly because of his refusal to come out of hiding. Like Salinger, like Robert Frost, like Ernest Hemingway, Philip generated a carapace that became a myth. In Frost’s case, the farmer-poet was the legend. In Hemingway’s, the sportsman-artist. In Salinger’s, the wrathful recluse determined to give his readers nothing more.

In Philip’s case, the myth was the good Jewish boy traduced by inner anarchy. Despite all the shifts and guises of fiction, it has been not so much protagonists as the man himself who, in book after book, keeps barging into the public eye, provoking adulation, hatred, learned commentary—everything but indifference. As with few other writers, readers have felt admitted into an inner sanctum they respond strongly to. At dinner one night in an Indian place on Broadway, the actor Richard Thomas, spruce in a white beard, said to Philip: “You’re the writer who’s meant most to me.” In a favorite restaurant on Third Avenue, a woman at the bar beckoned to me with a long forefinger. “Young man, is that Philip Roth you’re with?” I nodded. She passed me her card. “Tell him I’ve got a classic six on Park and am available.” Some variant of the encounter occurred when we went to any public place. Particularly on the Upper West Side. “Let’s have dinner on the East Side,” Philip would occasionally say. “Nobody knows me over there.”

If monogamy was anathema to him, so was enduring the opprobrium that the polyamorous suffer. In My Life as a Man, the hero, Peter Tarnopol, speaks for his maker when he says:

I may not be well suited for the notoriety that attends the publication of an unabashed and unexpurgated history of one’s erotic endeavors. As the history itself will testify, I happen to be no more immune to shame or built for public exposure than the next burgher with shades on his bedroom windows and a latch on the bathroom door—indeed, maybe what the whole history signifies is that I am sensitive to nothing in all the world as I am to my moral reputation.

Torment about rectitude plagued Philip as acutely as any itch in the loins. That a man who’d written those books and led that life should be so primly worried about what people were saying struck me as funny.

Prior to the 1980s, he’d just been one of the interesting writers. Some of his books meant little to me—The Breast, for instance, which is lousy any way you look at it. But then came marvels like The Ghost Writer, The Counterlife, Operation Shylock, and Sabbath’s Theater, proving him the best American novelist of his generation, our likeliest candidate for immortality. It was in 1994, the year before Sabbath’s Theater, that I met Philip. The occasion was our friend Joel Conarroe’s 60th birthday. The venue was the James Beard House on West 12th Street. There was Philip, aglow and triumphant: the dogged athlete who’d rebounded from orthopedic and mental breakdown, the natural bachelor who’d extracted himself from an untenable marriage, the tenacious self-reinventor who would soon publish Sabbath, his most scandalous book.

That night he was all speed and laughter, head thrown back—supernaturally quick with the next line. He asked what I’d been reading. I said Saul Bellow’s Herzog. “Yes, that loaf of bread a rat has burrowed into, leaving his rat shape, Herzog cutting slices from the other end.” Then he quoted a few lines from memory: “ ‘But what do you want, Herzog?’ ‘But that’s just it—not a solitary thing. I am pretty well satisfied to be, to be just as it is willed, and for as long as I may remain in occupancy.’ ” Before leaving he said, “Let’s have lunch, kid”—but there was to be no lunch for years.

In the summer of 1998, after reading bound proofs of I Married a Communist, I decided to write to him. I was struck particularly by the final pages, in which the narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, recalls his mother telling him that his grandfather has died and is now a star: “I searched the sky and said, ‘Is he that one?’ and she said yes, and we went back inside and I fell asleep.” Stars make sense anew to Nathan as an explanation of the dead, each of them a furnace burning away up there, “no longer impaled on their moment but dead and free of the traps set for them by their era.” No more calumny or betrayal. No more idealism or hope. Just the blazing heavens, “that universe into which error does not obtrude.”

A few days after I mailed my letter, the phone rang. It was Philip, wanting to talk. I felt at once that I was laughing with someone I knew well. Acrobatically unpredictable though the conversation was, I could follow his moves. Someone had to lead. Then he hung up without notice and I felt I’d been danced off the edge of the world.

Our first meal together, the first of hundreds, was three years after that. I’d moved back to New York full-time and he was there seasonally, and we decided to have the long-delayed lunch. He’d sent me The Dying Animal and proposed that we talk about it. I met him at a Thai restaurant called Rain, at Columbus and 82nd. The neighborhood around the American Museum of Natural History had already been Philip’s for more than 20 years.

“What do you think of my little book?”

Determined not to gush, I said that the scene where Consuela Castillo shows David Kepesh, her literature professor, her doomed, cancerous breasts reminded me of a similar scene in Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward, in which a young woman, on the night before her mastectomy, goes to the room of a young man sick with a cancer of his own and chastely asks him to worship her doomed right breast. “Today it was a marvel. Tomorrow it would be in the trash bin,” I said, quoting Solzhenitsyn. In the silence that followed, I felt our friendship begin.

Early on he told me this: “What I care about is individuals enmeshed in some nexus of particulars. Philosophical generalization is completely alien to me—some other writer’s work. I’m a philosophical illiterate. All my brainpower has to do with specificity, life’s proliferating details. Wouldn’t know what to do with a general idea if it were hand-delivered. Would try to catch the FedEx man before he left the driveway. ‘Wrong address, pal! Big ideas? No, thanks!’ ”

I mentioned a few characters of his whose intense particularity touches the universal: Mickey Sabbath, Swede Levov, Coleman Silk.

“Glad for the vote of confidence, but I aim only at specifics. Entirely for others to say whether some universal has been hit. I have, for instance, never—I repeat, never—written a word about women in general. This will come as news to my harshest critics, but it’s true. Women, each one particular, appear in my books. But womankind is nowhere to be found.”

“I’ve got an earworm, Ben.” I say, “There’s only one thing to drive out a worm, and that’s another worm,” and I sing, “Lydia, oh Lydia, oh Lydia, Lydia the tat-tooed lady!”

“I think that worked,” he says, shaking a finger in one ear. We’re on our way to Alice Tully Hall to hear the Emerson String Quartet. They’ve been doing Shostakovich’s string quartets in a series of evenings. Tonight is the conclusion.

Philip loves the intimacy of chamber music. Orchestral and classical vocal are not for him. The one time I got him to enjoy an opera, it was Shostakovich’s The Nose, hardly standard fare. Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, he refers to as Der Schmerz im Tuchas. He does allow that Strauss’s Four Last Songs are pretty good in the Elisabeth Schwarzkopf version. While he does not read music, he tends to grasp it in highly structural terms—exposition, development, reprise, etc.—and has a remarkable musical memory, along with a quicksilver way of finding metaphors for what he’s heard: “The scherzo is four madmen making up a dance as they go.” “The cello is bearing a grudge.” “The second violin is more confidential than the first.”

Following intermission he is rigidly at attention for Shostakovich’s 13th quartet. The elaborate pizzicati and strange slapping of the viola belly with the bow stick fascinate us both, as if composer and performers were trying to get at something more elemental than music.

Later, out on Broadway, we listen to a bespectacled, wild-haired, Upper West Side–type boy of about 14 expostulating with his father: “No, Dad, the violist has to climb into 13th position to play the unison note with the violins!” The unison note, if that’s what it’s called, was indeed a keening voice to send us home with. “How about that for a worm?” Philip asks. “Don’t think I’ll ever get it out of my brainpan.” Again he shakes a finger in his ear.

“Brainpan”: I go home and write that down. All of life up there in the brainpan, all of it somehow husbanded there. In old age, waiting for sleep, Philip would pick a year and revisit it month by month, week by week, room by room. “It’s all there. What happened is now the sum of me. A little patience, and the locks turn. I’m back wherever I choose to go.”

My own locks turn and I am at Philip’s country house, in the pool. I swim a few laps, then dog-paddle, then just float on my back. He comes out. “Found it!” he announces. “Opened the book and skimmed for 10 minutes and there it was. Goes like this, and you’re ideally situated to hear it: ‘A man that is born falls into a dream like a man who falls into the sea. If he tries to climb out into the air as inexperienced people endeavor to do, he drowns. The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up … In the destructive element immerse.’ This has been my credo, the lifeblood of my books. I knew it was from Lord Jim but didn’t know where. All I had to do was put myself in a trance and I found it: ‘In the destructive element immerse.’ It’s what I’ve said to myself in art and, woe is me, in life too. Submit to the deeps. Let them buoy you up.”

Another turn of the lock, and I am at Philip’s 74th-birthday celebration, in 2007. He’d said it would be tempting fate to hold out for 75, so a 74th was planned at the writer Judith Thurman’s townhouse. The garden has been tented in and a marvelous supper laid on. Afterward Philip asks, rather surprisingly, if anyone cares to recite a poem from memory. Mark Strand reels off one of his own (“In a field, I am the absence of field”), then looks at me as if to say, “Your serve.” What comes to mind and I recite, stumbling only once or twice, is Frost’s “I Could Give All to Time,” with its stirring conclusion:

I could give all to Time except—except

What I myself have held. But why declare

The things forbidden that while the Customs slept

I have crossed to Safety with? For I am There,

And what I would not part with I have kept.

“Those rhymes!” says Philip on the phone the following morning. “It’s as if nature made them.”

This essay was adapted from Benjamin Taylor’s new memoir, Here We Are: My Friendship With Philip Roth. It appears in the May 2020 print edition with the headline “Being Friends With Philip Roth.”