When Hunter S. Thompson Ran for Sheriff of Aspen

"Hunter represents something wholly alien to the other candidates for sheriff—ideas."

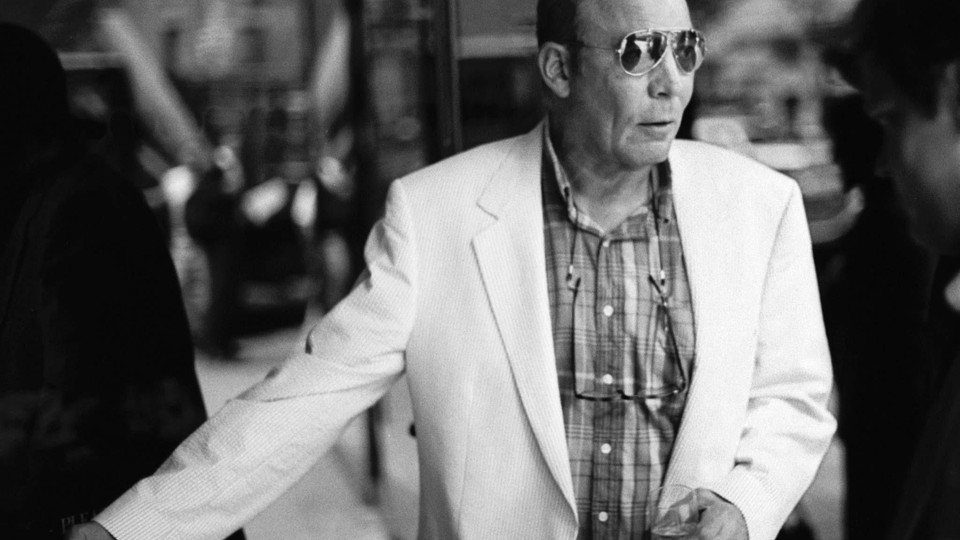

He was a self-confessed freak, a maniac, a drug fiend greatly enamored with guns, whiskey, and quantities of hallucinogens that could knock out entire metropolises at a time. And, in 1970, Hunter S. Thompson was also a candidate running to be sheriff of Aspen and the surrounding Pitkin County.

As ideas go, it was a curious one. Thompson, the godfather of gonzo journalism, had moved to Woody Creek, Colorado, in 1967 to join the flocks of writers, thinkers, hippies, and dropouts seeking a quieter life—albeit one still steeped in the counterculture. With the $15,000 royalty check he received for his first book, 1966's Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, Thompson purchased a home he named Owl Farm, where he lived until he committed suicide there in 2005. He became an all-day regular at the Hotel Jerome, holing up at the J-Bar and—legend has it—once almost drowning Bill Murray when he duct-taped the actor to a sun lounger and threw him into the hotel pool.

In 1969, an informal consortium led by Thompson decided to shake up the status quo in Aspen by getting involved in politics. He explained his mission in a Rolling Stone article called "Freak Power in the Rockies":

"Why not challenge the establishment with a candidate they’ve never heard of? Who has never been primed or prepped or greased for public office? And whose lifestyle is already so weird that the idea of 'conversion' would never occur to him? In other words, why not run an honest freak and turn him loose, on their turf, to show up all the normal candidates for the worthless losers they are and always have been?"

The candidate in question was Joe Edwards, a 29-year-old lawyer who had gained some notoriety the year before when he defended a group of hippies who'd been arrested for "vagrancy" in town. Edwards argued that the arrests were part of a pattern of institutional bias in Aspen wherein those who looked different were hassled by the local police force and its magistrate, Guido Meyer. He challenged Meyer's "unconstitutional" sentencing of beatniks and eventually had him removed from office.

Thompson's plan was to run Edwards as a candidate for mayor, but as the campaign progressed and it started to look like Edwards might actually win, it occurred to him that he himself could run for sheriff and do his own part toward reforming local politics:

The Old Guard was doomed, the liberals were terrorized, and the Underground had emerged, with terrible suddenness, on a very serious power trip. Throughout the campaign I'd been promising, on the streets and in the bars, that if Edwards won this Mayor's race I would run for Sheriff next year (November, 1970) … but it never occurred to me that I would have to actually run; no more than I'd ever seriously believed we could mount a "takeover bid" in Aspen.

Edwards eventually lost by six votes, but Thompson was galvanized to continue with his campaign, and the result was "one of Hunter's greatest times," as a friend later recalled. His campaign symbol was "a double-thumbed fist, clutching a peyote button" superimposed on a sheriff's star, which was featured on posters around town. His platform, detailed in Rolling Stone, called for the streets of Aspen to be ripped up with jackhammers and for the creation of "a huge parking and auto-storage lot on the outskirts of town," as well as for the town's name to be changed to "Fat City" in an effort to deter the "greed heads, land-rapers, and other human jackals from capitalizing on the name 'Aspen.'"

(Wikimedia Commons)

And, perhaps predictably, he proposed a relaxed policy for drug offenses, even as he noted that "any sheriff of any county in Colorado is legally responsible for enforcing all state laws regarding drugs—even those few he might personally disagree with." Thompson's caveat was that dishonest drug dealers should be set in stocks on the courthouse lawn, and that "it will be the general philosophy of the Sheriff's office that no drug worth taking should be sold for money."

During the campaign, Thompson shaved his head in order to be able to refer to the incumbent Republican Carrol D. Whitmire, who had a crew cut, as "my long-haired opponent." He wore Converse All-Stars and shorts to town hall meetings, where he spoke with surprising seriousness about the environment and the "silly" laws against marijuana. He made a campaign video that showed him riding a motorcycle through the mountains while his friend, writer James Salter, narrated an endorsement:

Hunter represents something wholly alien to the other candidates for Sheriff: ideas. And, a sympathy towards the young, generous, grass-oriented society which is making the only serious effort to face the technological nightmare we've created. The only thing against him is, he's a visionary. He wants too pure a world.

Thompson lost the election by 173 votes to his opponent's 204 and promptly quit politics, which is a shame because the "Fat City Ideas Festival" really has a nice ring to it. But his spirit lingers: Recreational marijuana was legalized in Colorado by state ballot in 2012.