A New Book Describes Hunter S. Thompson’s Prescience

“Trump is present on every page, even though he’s never mentioned once,” the author says.

If Hunter S. Thompson were still alive—if the so-called Gonzo journalist hadn’t killed himself in 2005, his ashes subsequently propelled from a cannon in a ceremony financed by Johnny Depp—the odds are high that he’d be linking Donald Trump to “that dark, venal and incurably violent side of the American character,” and contending that Trump “speaks for the Werewolf in us.”

That’s how Thompson reported on Richard Nixon back in his Rolling Stone ’70s heyday, when his anarchic attitude broke the rules of objectivity and bonded with his fans in that divisive era. He was, in a sense, America’s first blogger, and his tone seems eerily contemporary. Even a letter he wrote to a friend in 1965 sounds like a common lament in 2018: “I think there is a terrible angst on the land, a sense that something ugly is about to happen, an hour-to-hour feeling of nervous anticipation.”

One might argue that there’s no need for another book about Thompson—who has been repeatedly parsed by biographers, played by actors (Depp and Bill Murray), and deconstructed in a slew of academic dissertations (for instance, “as a modern practitioner of the carnivalesque in literature”)—but Timothy Denevi, an assistant professor at George Mason University, begs to differ. His new book, Freak Kingdom, tracks Thompson’s peak professional years, from 1963 to 1974, but in truth, Denevi says, “Trump is present on every page, even though he’s never mentioned once.”

Denevi tells me, “A lot of people today know Thompson as a drugged-out cartoon character”—indeed, the Doonesbury artist Garry Trudeau has made “Duke” a recurring character—“but what many of us are feeling right now [about Trump], Thompson was articulating beautifully in the ’60s and early ’70s, about how difficult it was to watch a government lie to its citizenry, and about how the country disfigured itself. When you’re constantly told one thing and you know the truth is another thing, the citizenry begins to fracture.

“That’s what we saw with the Vietnam War, with the Nixon administration and Watergate, with what Thompson saw as shameless, ruthless criminality. I think Thompson would look at the shameless criminality in the Trump administration, and he would’ve been able to dramatize the trauma of the situation, using the New Journalistic techniques.”

Not everyone, of course, loves the iconoclastic Thompson persona (the cigarette holder, the ever-present bottle of Wild Turkey), nor does every scribe and chronicler embrace the “New Journalistic techniques,” which combine reportage with the narrative devices typically associated with fiction. Thompson once wrote that “fiction is a bridge to the truth that the mechanics of journalism can’t reach … you have to add up the facts in your own fuzzy way,” and some journalists in recent decades, perhaps inspired by Thompson, have been accused of fuzzing the line that separates fact from fantasy, of inventing details in the pursuit of a higher truth.

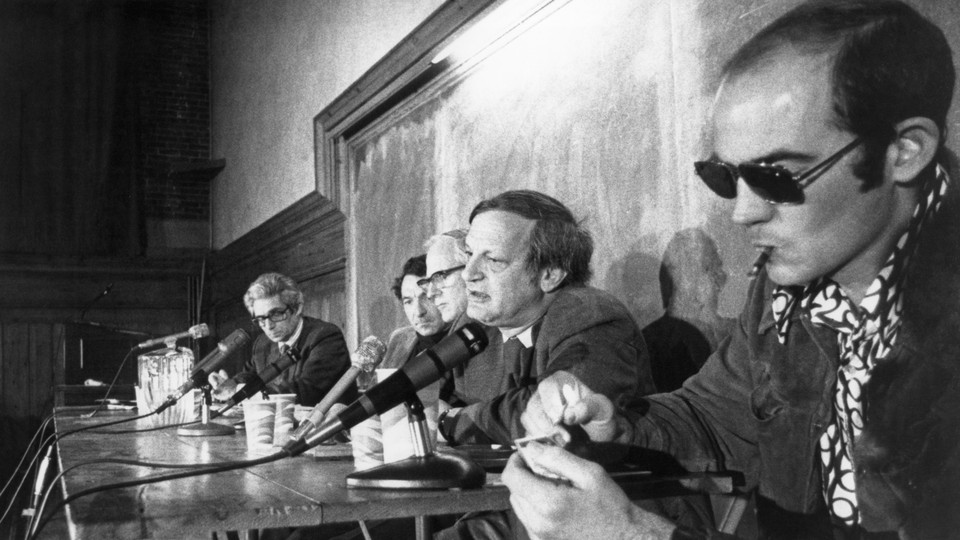

Nor does everyone in the news business endorse Thompson’s flagrant participatory style (hence the term Gonzo); in 1974, he told Playboy magazine, “I like to get right in the middle of whatever I’m writing about, as personally involved as possible”—which arguably skewed the reality he was covering. During his Rolling Stone stint at the 1972 Republican convention, he infiltrated a Youth for Nixon rally and told the kids that NBC News’s John Chancellor loved to drop acid. Because the kids hated the media, they believed his fake LSD rumor—which arguably heightened the reality he was covering, because it exposed the Nixon kids’ naïveté. (“Golly,” he quotes a girl as saying about Chancellor, “that explains a lot, doesn’t it?”)

Denevi defends Thompson’s immersive subjectivity, which was developed only after years of objective reportorial spadework; today, by contrast, “too many people have decided that the more opinions they have, the more likely they’ll get noticed. But there’s no inherent worth to the opinions … Tucker Carlson [on Fox News] thinks he’s Hunter Thompson, whereas in reality, he’s not reporting; he’s just an opinion who’s trying to further Trump’s power.”

The keepers of Thompson’s flame contend that his shoe-leather reporting provided ballast for observations that today seem prescient. He hung out for a year with the ’60s Hell’s Angels, and his descriptions—of white guys without college degrees, “rendered completely useless in a highly technical economy”—bring to mind Trump’s so-called forgotten Americans. Thompson said they were motivated by an “ethic of total retaliation.” He wrote: “They are out of the ball game and they know it, (so) they spitefully proclaim exactly where they stand … Instead of losing quietly, one by one, they have banded together with a mindless kind of loyalty and moved outside the (establishment) for good or ill. (That) gives them a power and a purpose that nothing else seems to offer.”

A year earlier, in 1964, he’d covered the Republican convention and captured the first populist rumblings that culminated in Trump’s nomination 52 years later. When the nominee Barry Goldwater declared that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” the delegates went wild. Thompson later wrote, “I remember feeling genuinely frightened at the violent reaction … As the human thunder kept building, they mounted their metal chairs and began howling, shaking their fists at Huntley and Brinkley up in the NBC booth—and finally they began picking up those chairs with both hands and bashing them against chairs other delegates were still standing on.”

He was similarly frightened and fascinated by George Wallace, the Alabama governor who twice sought the presidency with demagogic pitches to Americans who felt they’d been left behind in a time of profound cultural and technological change. After one Wallace rally in 1972, Thompson wrote, “The air was electric even before he started talking … He campaigns like a rock star (with) a thundering, gut level appeal to rise up and smash all the ‘pointy-headed bureaucrats in Washington’ who’d been (screwing) them over for so long”—although Wallace, in his appeals to emotion, “never bothered to understand the problems.”

It’s not a stretch to imagine how Thompson would have chronicled the contemporary chants of “Lock her up.” Denevi, the new biographer, tells me, “There’s something ugly in the American character, a sense of resentment, that very charismatic politicians have always tapped into. ‘Come to me, and I will give you the answers; they’re very simple.’” But how Thompson would handle Trump is, of course, a moot question, because the writer was burned out by 1980. His love of alcohol and Dexedrine sapped his strength, and a string of partisan disappointments—Robert Kennedy’s assassination, Nixon’s two electoral wins, Ronald Reagan’s ascent—sapped his spirit.

I witnessed that mood firsthand when I had dinner with Thompson (and several handlers) in June 1981. As I wrote at the time, he ordered two beers, two margaritas, and a Chivas Regal on the rocks to go with his ice cream. He said that he’d recently visited Washington, intending to write about Reagan; however, “we got there and said, ‘What the hell?’ I don’t give a damn … To be in Washington—jeez, what a horrible way to live.” He had depleted his capacity for outrage: “To keep writing angry, damn-you stuff can drive you mad.”

I described that dinner to Denevi. He replied, “I can understand Thompson’s exhaustion. That’s why he couldn’t continue to write the way he had.” He was disillusioned by what he perceived as the chasm between America’s promise and performance, “his perspective was eroded by his alcoholism,” and, ultimately, “he became a caricature of himself.” Indeed, when Trump briefly flirted with launching a 2000 presidential bid, Garry Trudeau contrived for cartoon Trump to hire cartoon Thompson as a backstage fixer.

But Denevi always thinks back to Election Night of 2016, when Trump’s flirtation finally came to fruition: “That moment—the emotion of it—put a fresh lens on Thompson … He was a patriot who wanted America to live up to its ideals.” Which is why Denevi believes that what Thompson chronicled in his inimitable way during the Nixon era—“America acting on its worst impulses”—still resonates today.

As Thompson once riffed, “Yesterday’s weirdness is tomorrow’s reason why.” That’s either wise or incoherent. Perhaps a new generation of scholars will parse it.