Skin In The Game

written by Jeff Marzick

The Kent State Massacre—Have We Learned Nothing In The Last 50 Years?

On May 4th, 1970 Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes ordered the National Guard onto the campus of Kent State University to quell an anti-war protest that had grown out of control. Fifty years later, another Ohio governor, Mike DeWine, also began issuing orders. First it was "shelter in place" in response to the coronavirus pandemic raging across the United States and the world, but then, along with governors around the country, the order was again to call in the National Guard—this time, in response to mass protests against the crumbling racist institutions we witness failing us at every turn.

The state of our union is precarious at best. Overwhelmed by a sense of hopelessness, of a palpable de-evolution of society at large, we are becoming witnesses to a daily breakdown of a system that was supposed to work for us, yet has instead become one that works for the very few. And just like the students who were at Kent State—those students who witnessed the violence—we all now carry that trauma, expressed by disillusionment, raised voices, and political actions. We all have skin in the game. Our young protestors today, however, are not only facing the National Guard in our cities, but also a hyper-militarized police apparatus, built up over the years by willing self-aggrandizing politicians.

The real question now is, have we not learned anything in the past 50 years?

On May 4, 1970, the National Guard opened fire on protesting students, killing four and wounding nine more. To be sure, many Americans today are unaware of the shootings. After all, the tragedy took place 50 years ago, and it generally isn’t discussed in the media unless it's a milestone year such as this. That—paired with the almost daily occurrence of mass shootings in 21st century American society—makes the Kent State shootings easy to forget, filed away somewhere between the summer of love and the watergate scandal. But since that fateful day 50 years ago, the Kent State’s May 4th Task force, in conjunction with university officials, have erected physical structures, as well as an interactive museum, that memorializes the event. One of the more poignant representations includes four concrete markers in the Prentice Hall parking lot, pinpointing the locations of the slain students—a constant reminder of the shootings on campus.

Kent State graduate student Eunice Reyes, who has parked in that lot and walks across it nearly every day, said the markers make an important statement. “I think there’s something incredibly powerful about something that people encounter daily, having such a wound located there,” she said. “I really am grateful that I’ve been able to attend Kent State and be around what happened on May 4 and be able to exist in that space.”

According to Kent Historical Society historian in residence, Roger Di Paolo, "May 4 was the perfect storm. You had a city that was not equipped in any way to deal with any unrest. You had a volunteer fire department in the 1970’s, you had a police chief who was well-intentioned but more equipped to handle a much smaller town."

When President Richard Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia in a speech delivered on April 30, 1970, the small university town in Northeast Ohio became a ticking time bomb. Clearly, Nixon’s address was interpreted as a widening of the war, and it, predictably, ignited the protests.

The following evening, North Water Street in downtown Kent erupted. After a night of heavy student partying in the area—long known for its abundance of bars and taverns—someone started a bonfire and rocks and beer bottles were hurled at windows. Before long, a full-fledged riot was in progress. Eventually, things quieted down, but the battle lines were drawn. Then, the mayor of Kent, LeRoy Satrom, made a phone call to the state capital in Columbus, requesting that the National Guard be on standby in case things got worse the following day.

And they did get worse.

Just as the Guard began rolling in on that Saturday, May 2, approximately a thousand demonstrators surrounded an old wooden building that served as barracks for the Army ROTC. A few of them set the building on fire, and the National Guard began firing tear gas to disperse the protestors. The next day was punctuated by another burst of hostile demonstrations in the evening, again ending with a barrage of tear gas. The Guard took control of the campus and announced the rally planned for the following day was prohibited.

Yet, by noon on May 4, about 2,000 people had gathered in the vicinity of the Commons on the university campus despite the decree. Soon, tear gas canisters were met with rocks and chants from the crowd and orders to disperse were ignored. Finally, at 12:23 p.m., near the crest of Blanket Hill, 28 guardsmen fired 61 to 67 shots in 13 seconds. The barrage of bullets lead to the deaths of Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, William Schroeder and Sandra Scheuer. Nine others were wounded. All of the casualties were students at Kent State. Krause and Miller had been participating in the protest, but Schroeder and Scheuer were just walking to class.

Four Dead in Ohio.

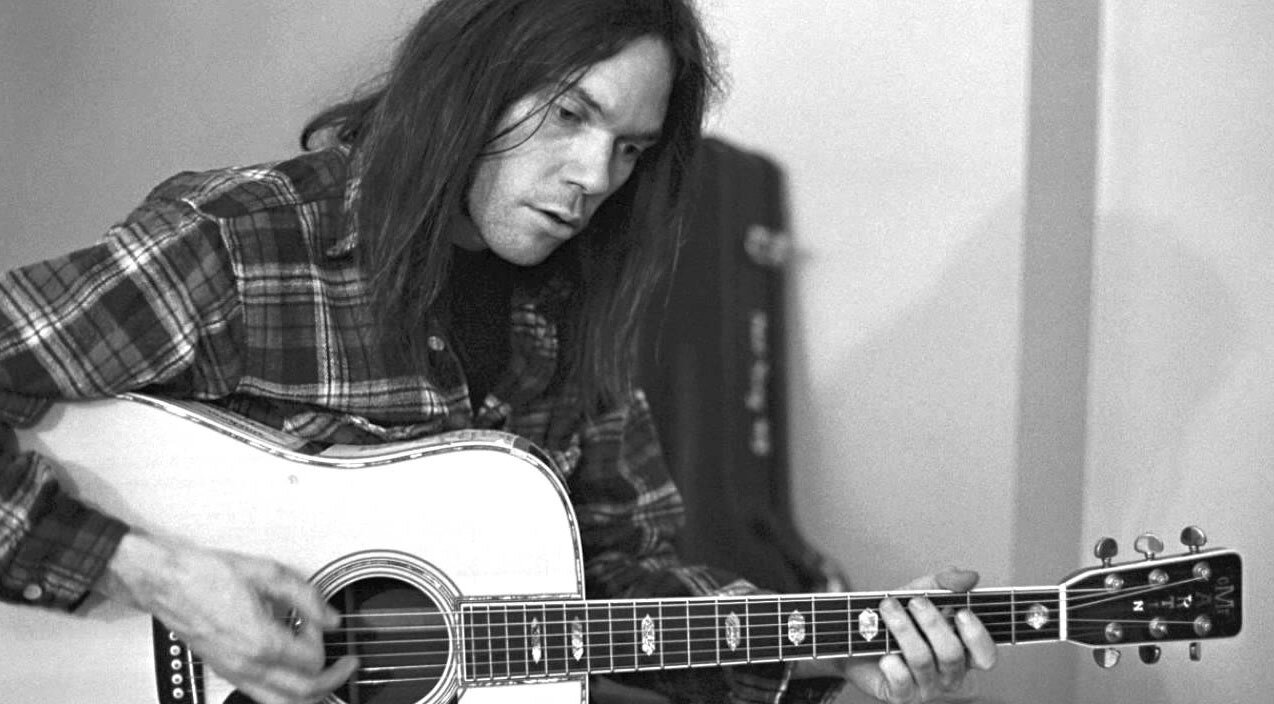

Not long after that tragic day at Kent State, musician Neil Young was visiting a friend in Butano Canyon near Pescadero, California, when he saw the cover of Time magazine with a picture of Allison Krause. The weight of the moment overwhelmed Young and prompted him to write what arguably is the most significant protest song in history: Ohio.

“These people were our audience,” Young wrote in his autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace. “That's exactly who we were playing for. It was our movement, our culture, our Woodstock generation. We were all one. It was a personal thing, the bond we held between the musicians and the people of the culture: hippies, students, flower children, call them what you will. We were all together.” He goes on: “I picked up my guitar and started to play some chords and immediately wrote Ohio; four dead in Ohio. The next day, we went into the studio in LA and cut the song. Before a week had passed, it was all over the radio."

On the 50th anniversary of the tragedy, Young's longtime pal and band partner, David Crosby (who sang on the original recording), reflected on the song and shootings via video. "These kids weren't outside agitators. They were your kids, your children,” he said. “They were simply protesting a war they did not believe in. And they were killed. I can never get that out of my head. So when I sing Ohio, I mean it.”

And Neil wasn’t the only artist directly affected by the inexplicable tragedy. In fact, some of the most well-known rock stars of that generation were students at Kent State at the time of the shootings. Nearby Akron, Ohio native, and iconic lead singer of the Pretenders, Chrissie Hynde, was at the protest that day. In her memoir "Reckless: My Life as a Pretender," Hynde wrote, "I knew Jeff Miller had been a fan of Neil Young. So I was happy that Young had become our spokesman, our voice. It was a big element in easing us out of shock."

Eagles legend Joe Walsh was a former Kent State student who also witnessed the shootings. In an interview with The San Diego Union-Tribune in 2012, Walsh said, "Being at the shootings really affected me profoundly. I decided that maybe I don't need a degree that bad."

Also on campus that day were other Kent State students who went on to rock ’n' roll fame, including Chris Butler (a friend of Jeffrey Miller’s) who formed The Waitresses and wrote the hit song "I Know What Boys Like," and future Devo members Gerald Casale and Bob Lewis. In fact, Butler, Walsh, Casale, Lewis, and Terry Hynde, Chrissie's brother, all lived a few doors from each other at an apartment building on Longmere Drive near downtown Kent and the campus.

That so many future rock stars lived so close to one another in a small, conservative town, attended the same school, and witnessed one of the most tragic events of the 20th century, speaks volumes. Casale said it best: "Devo wouldn't have happened if it hadn't been for Kent State. That's the long and short of it."

Casale, writing an op-ed for Rolling Stone magazine 50 years later, was in the thick of it on May 4 and was a good friend of Miller's: "I turn around, and I see a guy on his belly on the road. People are starting to gather around, and there's blood running out of his head and neck area. The blood is glistening in the noon sun. I realize it's Jeff Miller. I get sick to my stomach, and I feel like I'm going to pass out."

"I sat down on the grass," Casale recalled. "About 30 seconds later, I realize people are screaming, 'Allison! Allison!' I can't really see her, but I see everyone hovering around somebody lying on their backs in the student/teacher parking lot, not moving. That turned out to be Allison Krause."

One of the other tragic ironies of May 4 was the fact that members of the National Guard who did the shooting were, in fact, peers of the students. Casale wrote, "You gotta understand the people shooting are the same age as the people they just killed. They were all standing there, freaked. They aren't moving, either. They realize what they've done."

In many ways, the event represented a climactic end to the previous decade’s bloody and tumultuous social and political revolution. America came out of the 1960’s bruised, battered and changed forever—people died in the streets for demanding civil rights, leaders were struck down by assassins' bullets, and a war fought in Southeast Asia would wind up taking the lives of over 58,000 Americans. Everyone was pissed about something, it seemed.

And universities were always part of the mix. Coming out of the so-called conformist culture of the 1950s, colleges became the hotbed of social and political movements, starting with the rise of the New Left, a movement bandied by disillusioned college students, intellectuals, and activists across the globe. One group that developed within the New Left was the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), founded in 1959 and initially inspired by the African-American civil rights movement. In 1962, the group issued a political manifesto called The Port Huron Statement, which was highly critical of racial discrimination and economic inequality in America, as well as the influence of corporations and trade unions.

Eventually, SDS shifted most of its focus to opposition to the Vietnam War, using mass protest strategies, direct action and civil disobedience. By the end of the 1960s, the group had become increasingly militant, occupying buildings on campuses across the country.

The organization eventually split into factions. One of the most notorious was the Weather Underground, whose violent actions were well-chronicled. It isn’t hard to figure out why such impassioned fervor infected the anti-war movement at the time. Whereas today we have an all-volunteer military, during the Vietnam era we had the draft. The students at Kent State and other universities around the country saw the evening news every night. Most knew friends or friends of friends who fought in the war and never came back.

Contrast Vietnam with the most recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and you get a sobering picture of how much military service participation rates as they pertain to the overall population of the United States have changed. During the Vietnam conflict from 1964-1973, over 8.7 million Americans served in the armed forces, and more than 2.7 million served in the war theater itself. Over 58,000 were killed and 153,000 wounded. Those who served represented roughly 9.7% of the US population at the time.

During the Iraq/Afghanistan conflicts from 2001-2020, over 3.3 million have served in the armed services, with roughly 2.7 million in the war theater and over half deploying multiple times. To date, approximately 7,000 have been killed and 53,000 wounded. Service members who have served since 2001 represent only about 1% of the current US population.

It's pretty simple. US college students protesting the war in the 1960’s and ’70’s had skin in the game. After all, they could have been drafted and forced to fight. Students today might see climate change or even school shootings themselves as their emergency call to arms. The kind of sustained and intense protests of the Vietnam era never materialized in response to the current conflicts in Iraq in Afghanistan.

Even though the Selective Service by law requires men ages 18 to 25 to register for the armed forces, the system has been all-volunteer since Vietnam. While the American people are war-weary and tired of the current conflicts, both Iraq and Afghanistan have wound down to the point where we seldom notice the casualties. That's what happens when only a small fraction of families in the country have lost loved ones to war. But these casualties were certainly noticed when the National Guard opened fire on protesting students on May 4, 1970. There were 428 military deaths in that month alone, with a total of 6,173 deaths for the entire year.

Skin in the game.

But while the college students of today don't have to worry about being forced to serve in military theaters around the world, it's not like they aren't enduring hardships in other ways, especially when it comes to paying for their education. The kids attending Kent State back in the day didn't have to worry about guns, climate disaster, or the crushing debt that today's students are all buried under. It's not even close. Consider that at the time of the shootings in May 1970, the average yearly cost for a four-year college degree at a public university was $323. As of the 2018-19 school year, this average grew to $10,230, according to the National Center for Education Statistics and The College Board. That’s a mind-blowing increase of 3,009 percent.

In the wealthiest country on the planet, you'd think we might be able to figure out a way to make it easier for our young people to attend college. Former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, a Democratic senator from Vermont, proposed a tuition-free program for any American who wanted to go to college. And Sanders struck a nerve with young people and enjoyed widespread support among college students.

With the COVID-19 pandemic nudging America toward a second Great Depression, however, what kind of prospects do kids have today? It wasn't that great before the coronavirus, and it's not going to be great when we get through this nightmare.

We ask a lot of our young people, as we indeed asked a lot of them in the 1960s. But back then, what we asked them to do could have gotten them killed. We sent them to Vietnam, supposedly to stop the spread of communism, but it turned out to be a huge mistake. So many lives were lost, and for what?

On May 4, 1970, four students lost their lives when our government decided this activism had gone too far. After all, Gov. Rhodes called the protesters “some of the worst types of people we harbor in America.” The breakdown of society we are witnessing has garnered the same intensity and anger we saw at Kent State and other universities during those tumultuous times. And today, with countless unregulated channels and illegitimate media sources, everyone is fractured. We're all in our own corners of the world, searching for like-minded news and information.

So maybe it really does take skin in the game. Just like the students who witnessed the tragedy at Kent State lived with that trauma, we move through these horrible days, with no end in sight. We are in a moment when young people, and the rest of us, have finally begun to say: “Enough of this shit.”

While the May 4, 1970 may not ring a bell for most Americans, the significance of that day should never be forgotten. When a government decides it has had enough, it will resort to any means necessary to silence the agitators. Perhaps it's one of the significant lessons of May 4, besides. Never underestimate the power of a government on its heels—its policies gone terribly wrong. People will pay, one way or the other.

The four students on the campus of Kent State University in 1970 certainly took one for the team—their loss having expedited the end of the terrible war their fellow students were there to protest. But it shouldn't have happened. We should not be turning weapons of war on our fellow citizens.