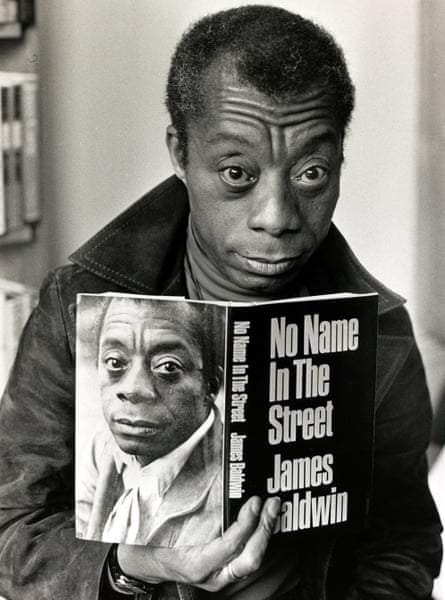

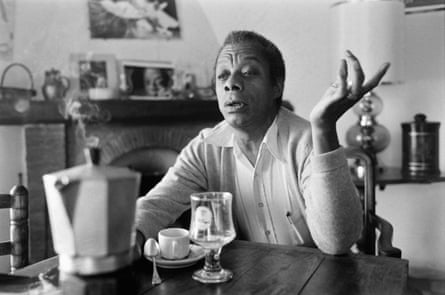

In the opening to his 1962 New Yorker essay Letter from a Region in My Mind, James Baldwin remembers walking around his neighbourhood of Harlem as a 14-year-old, wondering if his fate would trap him there. “What I saw around me that summer in Harlem was what I had always seen,” he wrote. “Nothing had changed.” More than 50 years on, Baldwin’s words and philosophy have travelled thousands of miles from 110th street. His public image has been on a journey, from literary sensation with his debut novel Go Tell It on the Mountain in 1952 to his searing non-fiction work in the 60s that saw him revered as one of America’s most prominent public intellectuals. Thirty years since he died of stomach cancer in 1987, an expat in the south of France, there is reinvigorated interest in Baldwin and his ideas. February sees the release of I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary by Haitian director Raoul Peck that takes Baldwin’s final, unfinished project – a book about the lives and murders of his friends Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers – as a starting point, before analysing Baldwin’s sometimes strained and difficult relationship with the civil rights movement. In March, Taschen will publish a special edition of The Fire Next Time with images from Life magazine photographer Steve Schapiro.

Peck’s film is the latest in a string of events and retrospectives that have put Baldwin back in the public imagination. The ball began rolling in 2014 with Columbia University’s year-long programme pegged to his 90th birthday. Since then, there have been film festivals, exhibitions dedicated to Baldwin, and musical theatre inspired by his writing. As the Black Lives Matter protests unfolded around the US, there was a collection of writing – including an entry from the Pulitzer winner Isabel Wilkerson – which took inspiration from Baldwin. His work has been used to explain everything from Trump to Dylann Roof and the Charleston church shooting. Then, in 2015, came Ta-Nehisi Coates’s bestseller turned must-read commentary on contemporary race relations in America, Between The World And Me, which was inspired by Baldwin’s own essay collection, The Fire Next Time.

For Baldwin scholar, professor of English at Yale and author Caryl Phillips, the return of Baldwin to mainstream thinking isn’t surprising at all. For him the big issues concerning American life now – the rise of crude, racially charged politics, killings of unarmed black men by the police, an apathetic public – repeat a history from which Baldwin’s critiques still offer some solace. “People are looking for someone who can articulate these issues,” says Phillips. “I think the person who has probably articulated what it means to be an American and what it means to be black, with more eloquence than anybody else in the last century, is Baldwin.”

For Peck, Baldwin’s writing has lasted because it was so ahead of its time. It looked beyond the binary racial politics of 1950s and 60s America, toward a future that could genuinely be called post-racial. “He always writes from the point of view that was not only politically right, but from a humanistic point of view – it was never just about race for him.”

Phillips agrees: “It would have pleased him greatly to see Obama in the White House. He’s a man who comes out of what Baldwin would have recognised as the true crucible of American life, which is fusion and hybridity. People coming together from different backgrounds to make a new country. That’s what he was saying, and that didn’t go over well with the clumsy racialised politics of the times.”

“He had the longer view,” says Peck. “It was about the legacy.”

That legacy is what’s at the heart of Peck’s documentary. He carefully illustrates how Baldwin is still relevant to contemporary America. By switching black and white footage of protests from the 60s into colour, and contemporary colour footage from Ferguson into black and white, Peck makes those events interchangeable. Those images, combined with Baldwin’s words read by Samuel L Jackson, affirm Baldwin’s status not only as a visionary writer, but a philosopher we can still turn to.

During a period when police shootings of unarmed black men and women are under the microscope, Baldwin’s writing about the creation of “the nigger” as a way to justify the subjugation of African-America still feels applicable. His theory that segregation of both physical and mental spaces is America’s biggest hurdle rings true with parallel, unequal systems composed along racial lines – for housing, religion and education – is still on the national agenda. Baldwin, a gay black man writing about interracial relationships in the 50s, wrestled with identity politics at a time when intersectionality was a word most people would think referred to the highway code.

Peck wanted to show how Baldwin fits perfectly into contemporary life. “[I wanted to] remind people that this man has given us all the instruments we need already, and, connecting it to Ferguson, which was happening when I was working on the film, it was like history catching up with the film. My intention was to bring his work to the forefront again. It was never intended to be a historical piece.”

But there was a time when Baldwin was savaged by his peers, publicly attacked by the more militant black leaders of the time, among them Eldridge Cleaver (whose criticism was dripping in homophobia) and Amiri Baraka, who saw his integrationist stance as compromised and weak. Publishers and editors wouldn’t touch him, either. Time magazine turned down his offer of a conversation with Josephine Baker because he was seen as old hat, and I Am Not Your Negro’s starting point is Baldwin’s continued struggles to get his work published after years of poor reviews and dwindling sales.

That outsider status, both at the time of the civil rights struggle and in the twilight of his career are, for Phillips, what make Baldwin timeless. He took risks, and history has rewarded him for it.

“The fact that he managed to achieve what he did – to keep publishing, to keep writing, to keep speaking, to not [succumb] to the pressure to become just a vocal spokesperson and a hip echo chamber for the most popular position of the day, is a remarkable achievement.”

Unlike his peers who took a hardline position – such as Malcolm X’s by-any-means-necessary stance, and the Black Panthers militancy – and offered solutions, Phillips argues, Baldwin’s job was to bear witness. He read between the lines and attempted to make sense of the world. “He explores the ambiguities and the ironies of the situation and helps you to see the problems more personally and clearly, and then leaves it up to you to draw the conclusions.

“I think when you’re younger and you’re trying to find answers, I don’t think Baldwin is the person you go to. I think when you recognise and you become aware of the complexity of the problem, then you want to go to someone who articulates the complexity and is prepared to rest with ambiguity.” For Peck, Baldwin hasn’t been so much out of fashion as a constant, uncited influence on writers. “Ten or 12 years ago, I said it was the time to go back to him because he had become somehow forgotten,” he says. “People didn’t see how important he still is. There was a new generation that was basically using him, and the knowledge of his work, but without giving him credit.”

I Am Not Your Negro opens the Human Rights Watch film festival in London on 9 March

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion