This story first appeared in the October 29 and November 26, 1984, issues of New York Magazine. We’re republishing it here, along with “Truman Capote in Hot Water,” on the society scandal that erupted around one of the author’s stories, to accompany release of the limited series Feud: Capote vs. the Swans.

Part I

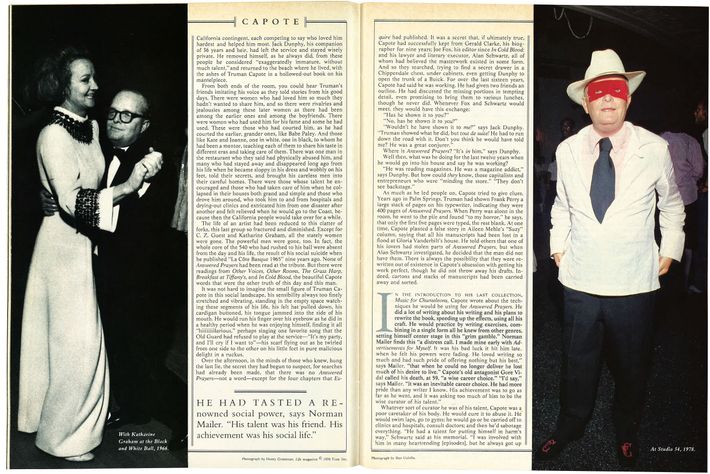

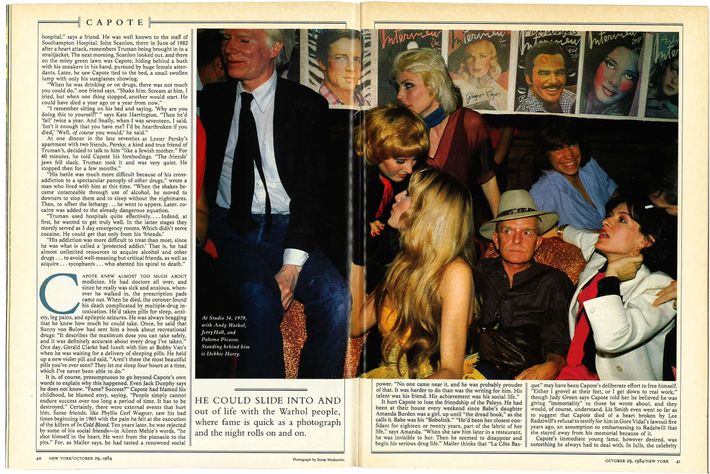

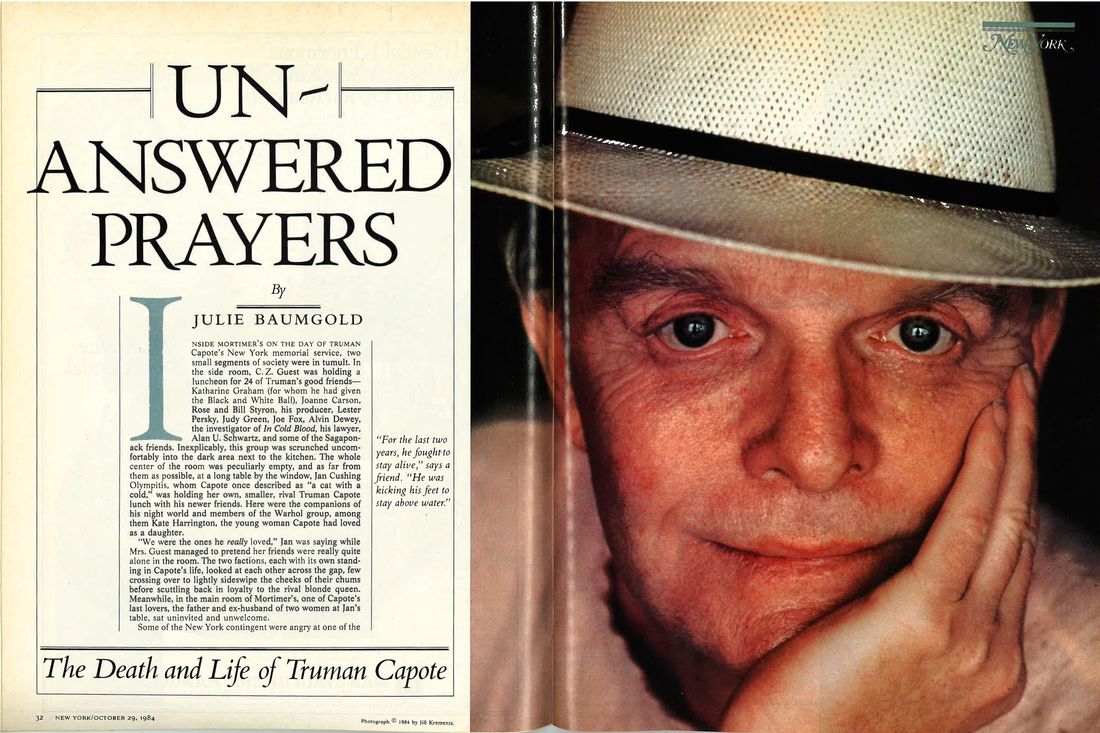

Inside Mortimer’s on the day of Truman Capote’s New York memorial service, two small segments of society were in tumult. In the side room, C. Z. Guest was holding a luncheon for 24 of Truman’s good friends — Katharine Graham (for whom he had given the Black and White Ball), Joanne Carson, Rose and Bill Styron, his producer, Lester Persky, Judy Green, Joe Fox, Alvin Dewey, the investigator of In Cold Blood, his lawyer, Alan U. Schwartz, and some of the Sagaponack friends. Inexplicably, this group was scrunched uncomfortably into the dark area next to the kitchen. The whole center of the room was peculiarly empty, and as far from them as possible, at a long table by the window, Jan Cushing Olympitis, whom Capote once described as “a cat with a cold,” was holding her own, smaller, rival Truman Capote lunch with his newer friends. Here were the companions of his night world and members of the Warhol group, among them Kate Harrington, the young woman Capote had loved as a daughter.

“We were the ones he really loved,” Jan was saying while Mrs. Guest managed to pretend her friends were really quite alone in the room. The two factions, each with its own standing in Capote’s life, looked at each other across the gap, few crossing over to lightly sideswipe the cheeks of their chums before scuttling back in loyalty to the rival blonde queen. Meanwhile, in the main room of Mortimer’s, one of Capote’s last lovers, the father and ex-husband of two women at Jan’s table, sat uninvited and unwelcome.

Some of the New York contingent were angry at one of the California contingent, each competing to say “who loved him hardest and helped him most. Jack Dunphy, his companion of 36 years and heir, had left the service and stayed wisely private. He removed himself, as he always did, from these people he considered “exaggeratedly immature without much talent” and returned to the beach where he lived, with the ashes of Truman Capote in a hollowed-out book on his mantelpiece.

From both ends of the room, you could hear Truman’s friends imitating his voice as they told stories from his good days. There were women who had loved him so much they hadn’t wanted to share him, and so there were rivalries and jealousies among these later women as there had been among the earlier ones and among the boyfriends. There were women who had used him for his fame and some he had used. There were those who had courted him, as he had courted the earlier, grander ones, like Babe Paley. And those like Kate and Joanne, one in white, one in black, to whom he had been a mentor, teaching each of them to share his taste in different eras and taking care of them. There was one man in the restaurant who they said had physically abused him, and many who had stayed away and disappeared long ago from his life when he became sloppy in his dress and wobbly on his feet, told their secrets, and brought his careless men into their careful homes. There were those whose talent he encouraged and those who had taken care of him when he collapsed in their houses both grand and simple and those who drove him around, who took him to and from hospitals and drying-out clinics and extricated him from one disaster after another and felt relieved when he would go to the Coast, because then the California people would take over for a while.

Cover Story

The life of an artist had been reduced to this clatter of forks, this last group so fractured and diminished. Except for C. Z. Guest and Katharine Graham, all the stately women were gone. The powerful men were gone, too. In fact, the whole core of the 540 who had rushed to his ball were absent from the day and his life, the result of his social suicide when he published “La Côte Basque 1965” nine years ago. None of Answered Prayers had been read at the tribute. But there were readings from Other Voices, Other Rooms, The Grass Harp, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and In Cold Blood, the beautiful Capote words that were the other truth of this day and this man.

It was not hard to imagine the small figure of Truman Capote in this social landscape, his sensibility always too finely stretched and vibrating, standing in the empty space watching these segments or his life, his felt hat pulled down, h!s cardigan buttoned, his tongue jammed into the side of his mouth. He would run his finger over his eyebrow as he did in a healthy period when he was enjoying himself, finding it all “hiiiiiiiilarious,” perhaps singing one favorite song that the Old Guard had refused to play at the service — “It’s my party, and I’ll cry if l want to” — his scarf flying out as he twirled from one side to the other on his little feet in pure malicious delight in a ruckus. Over the afternoon, in the minds of those who knew, hung the last lie, the secret they had begun to suspect, for searches had already been made, that there was no Answered Prayers — not a word — except for the four chapters that Esquire had published. It was a secret that, if ultimately true, Capote had successfully kept from Gerald Clarke, his biographer for nine years; Joe Fox, his editor since In Cold Blood; and his lawyer and literary executor, Alan Schwartz, all of whom had believed the masterwork existed in some form. And so they searched, trying to find a secret drawer in a Chippendale chest. under cabinets, even getting Dunphy to open the trunk of a Buick. For over the last 16 years, Capote had said he was working. He had given two friends an outline. He had discussed the missing portions in tempting detail, even promising to bring them to various lunches, though he never did. Whenever Fox and Schwartz would meet, they would have this exchange:

“Has he shown it to you?”

“No, has he shown it to you?”

“Wouldn’t he have shown it to me?” says Jack Dunphy.

“Truman showed what he did, but lout de suile! He had to run down the road with it. Don’t you think he would have told me? He was a great conjurer.”

Where is Answered Prayers? “It’s in him,” says Dunphy.

Well then, what was he doing for the last 12 years when he would go into his house and say he was working?

“He was reading magazines. He was a magazine addict.” says Dunphy. But how could they know, those capitalists and entrepreneurs who were “minding the store.” “They don’t see backstage.”

As much as he led people on, Capote tried to give clues. Years ago in Palm Springs, Truman had shown Frank Perry a large stack of pages on his typewriter, indicating they were 400 pages of Answered Prayers. When Perry was alone in the room, he went to the pile and found “to my horror,” he says, that only the first five pages were typed, the rest blank. At one time, Capote planted a false story in Aileen Mehle’s “Suzy” column, saying that all his manuscripts had been lost in a flood at Gloria Vanderbilt’s house. He told others that one of his lovers had stolen parts of Answered Prayers, but when Alan Schwartz investigated, he decided that the man did not have them. There is always the possibility that they were rewritten out of existence in Capote’s obsession with getting his work perfect, though he did not throw away his drafts. Indeed, cartons and stacks of manuscripts had been carried away and sorted.

In the introduction to his last collection, Music for Chameleons, Capote wrote about the techniques he would be using for Answered Prayers. He did a lot of writing about his writing and his plans to rewrite the book, speeding up the effects, using all his craft. He would practice by writing exercises, combining in a single form all he knew from other genres, setting himself center stage in this “grim gamble.” Norman Mailer finds this “a distress call. I made mine early with Advertisements for Myself. It was his bad luck it hit him late, when he felt his powers were fading. He loved writing so much and had such pride of offering nothing but his best,” says Mailer, “that when he could no longer deliver he lost much of his desire to live.” Capote’s old antagonist Gore Vidal called his death, at 59, “a wise career choice.” “I’d say,” says Mailer, “it was an inevitable career choice. He had more pride than any writer I know. His achievement was to go as far as he went, and it was asking too much of him to be the wise curator of his talent.”

Whatever sort of curator he was of his talent, Capote was a poor caretaker of his body. He would cure it to abuse it. He would swim laps, go to gyms; he would go or be carried off to clinics and hospitals, consult doctors; and then he’d sabotage everything. “He had a talent for putting himself in harm’s way,” Schwartz said at his memorial. “I was involved with him in many heartrending [episodes], but he always got up and threw himself into the fray.” At various times, Capote was reported to have throat polyps, prostate problems, a tic douloureux. He did have liver disease, epilepsy, emphysema, and phlebitis, but his hard little body, as stubborn and solid as the bulldogs he collected, kept mending, and his will did the rest. “He could rejuvenate faster than anyone I knew,” says a doctor who treated him. “For the last two years, be fought to stay alive. He was kicking his feet to stay above water, not like before, when you felt he was going straight for a nosedive,” says Kate Harrington. His death came when he was drinking less, when the turbulent companions were gone, and when he was fighting phlebitis, the disease that frightened him as nothing physical had before. In the last few years, he would have stints when he was spartan, during Music for Chameleons and for months last winter and spring, though he had been drinking again over the summer. It was a bad summer. Quite typically, this June he fled his last drying-out place, checking out of Chit-Chat Farms after only five days, paying $600 for a limousine to get him home quick.

“He’d be rueful,” says a friend, “but he denied his problem — ‘It has nothing to do with drinking. It’s just bad luck.’ He’d take Antabuse and drink right through it.”

All his life, Truman Capote knew how to seduce, the way certain small children (like the child in his story “Miriam”) do. He was full of wiles and guile, talking low so you couldn’t lean back in your seat with him as he told one of his stories, usually something dreadful about someone impeccable. He loved to shock. The mother of two famous sisters had called her daughters “whores” during one of their screaming fights. The penis of one famous writer was actually “a cross between a dimple and a bellybutton.” He had his network of informants and the classic gossip’s desire to know it all. In the days when he cared, he was not above asking one editor who on her staff was having affairs. He saw through social poses because, somehow, he knew all worlds, from his underground of pimps, druggies, and whores to the now aging stories from the days of his high life.

Capote was perverse in all things. Though his public mannerisms were effeminate, there was a masculine, almost sexy core to this man who knew himself so well and presented his outrageousness boldly and with calculation. Intensely competitive as he was, and jealous of all his turfs, he was yet a fierce protector of other writers’ talent. He was proud of Jack Dunphy’s writing all his life. And though he wrote cruelly about a minimally disguised Tennessee Williams in Answered Prayers, he dedicated Music for Chameleons to him in a low period of Williams’s career.

He told women of a certain age to keep to one look, and that way they would never age. He told his women bow to dress, what makeup to wear, what to see or read, who to love. He waited at their hairdressers, waited in their libraries. Wear glasses and low heels in reptile, he said to one, happily wasting his writer’s eye. He took care of them, moving them into new houses, sending them to Norman Orentreich for their skin, running their lives as he had when he tried to launch Lee Radziwill as an actress in Laura, or to set up a house-opening business for his cleaning lady. After he gave a reading to a fashionable audience at the Newhouse Theater, Lester Persky found him in his dressing room cackling away with his cleaning woman and her four friends. When Katharine Graham was nervous about traveling with him without having read all his work, he marked a collection for her of what she should read. He assured her she’d be all right in a more social world than she was used to at the time. Aileen Mehle remembers that when she stayed with him once in Palm Springs, “he treated me as though I were a little doll. He tucked me in bed and told me bedtime stories and gave me a bit of Answered Prayers to read.”

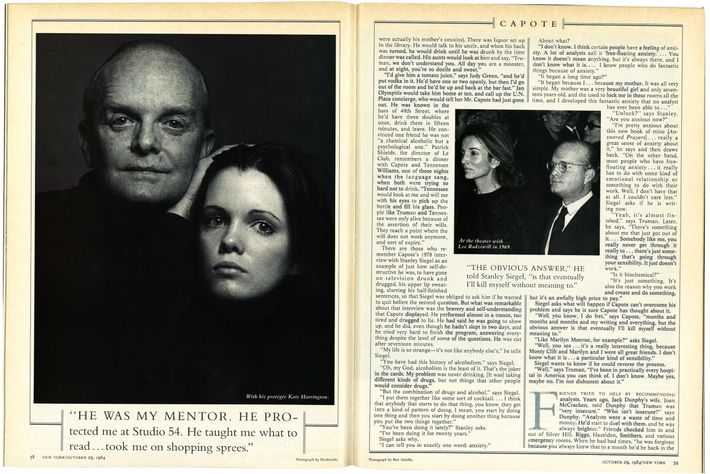

“He was my mentor,” says Kate Harrington. “With all his enfant terrible behavior, with me he was not that way. He protected me at Studio 54. He taught me what to read, took me on shopping sprees, asking, ‘Do you think this is pretty? Isn’t this chic?’ We went looking at pictures, and he taught me to observe. At the end of parties, he would sit on my bed and say, ‘What did you see?’ He taught me how to talk. I’d say, ‘I’m taking a bath,’ and he would say, ‘You’re not taking a bath, you’re bathing.’” He made sure she kept out of the sun, having her paged on one California trip whenever she sneaked out to the pool. He had Avedon photograph her for her 14th birthday, and gave her pearls from Tiffany for her high-school graduation: “The real thing, for the real thing,” he wrote. But as she grew, he changed, and she found herself having to take care of him these last years.

All Capote’s friends geared up for him, for he was the best company, not only for the women but for the night people too. Once, he went over to a little gay kid at Studio 54, as thin as a sparrow, and just put his arms around him and held him. The husbands and the big businessmen were comfortable with him, as attracted to the stories and gossip as were their wives. Before the break, William Paley used to call Capote “Tru-boy,” and he could be seen sitting parked in front of CBS in Paley’s car, waiting for him. Robert O. Anderson, the chairman of Atlantic Richfield, once sent Truman in his private plane to his Mexican house and then took the plane away so Truman would be forced to write. For all of them, Truman always went a bit further: going along 49th Street to find a new shop for his barber, giving a People writer copies of his books and driving her all the way to the expressway so she wouldn’t get lost, dropping off pies and a quilt at the summer house of Jill Krementz and Kurt Vonnegut, befriending and supporting the family of a lover during and after their affair.

He loved people who were “slightly manqué,” and he loved pranks and mischief. The first time he met Leo Lerman, he jumped on Lerman’s back and said, “Give me a piggyback.” He’d call Krementz and imitate a telephone repairman. When Aileen Mehle was going to London, he hurt her by lying about her and a British banker. “I knew you were going there, and I thought it would be fun if we stirred up the pot,” he told her later. When he first met one of his later women, she told him she was seeing an analyst he had once gone to. Capote had her go in for her next appointment and say, “Doctor, I’m so happy. I’ve finally found the man for me. He’s warm and stable and everything you told me to look for.” A very nervous nurse came in just then to announce that Mrs. X’s fiancé was in the waiting room. At that point, Truman burst in, pulling her away, saying, “Darling, you were so quiet when you got out of bed this morning I didn’t hear you go.” And, laughing, out they ran to lunch at Quo Vadis. “He went from an imp to a gremlin. From something adorable and sweet to hold in your hand to almost a rocklike creature,” says a friend.

Truman Capote’s best years ended in the ’70s. The mid- to late ’70s were very hard times. Then began the desertion of friends, and the feuds with Jacqueline Susann, Gore Vidal, and Lee Radziwill. The collapses, with Capote limp on a stretcher, increased then, too, building to four in two months of 1981. In 1977, he had walked onstage at Towson State University in Maryland announcing he was an alcoholic.

He told a writer about his childhood in Alabama, when he lived with his maiden aunts and an uncle who drank (they were actually his mother’s cousins). There was liquor set up in the library. He would talk to his uncle, and when his back was turned, he would drink until he was drunk by the time dinner was called. His aunts would look at him and say, “Truman, we don’t understand you. All day you are a monster, and at night, you’re so docile and sweet.”

“I’d give him a tomato juice,” says Judy Green, “and he’d put vodka in it. He’d have one or two openly, but then I’d go out of the room and he’d be up and back at the bar fast.” Jan Olympitis would take him home at ten, and call up the U.N. Plaza concierge, who would tell her Mr. Capote had just gone out. He was known in the bars of 49th Street, where he’d have three doubles at once, drink them in 15 minutes, and leave. He convinced one friend he was not “a chemical alcoholic but a psychological one.” Patrick Shields, the director of Le Club, remembers a dinner with Capote and Tennessee Williams, one of those nights when the language sang, when both were trying so hard not to drink. “Tennessee would look at me and will me with his eyes to pick up the bottle and fill his glass. People like Truman and Tennessee were only alive because of the assertion of their wills. They reach a point where the will does not work anymore, and sort of expire.”

There are those who remember Capote’s 1978 interview with Stanley Siegel as an example of just how self-destructive he was, to have gone on television drunk and drugged, his upper lip sweating, slurring his half-finished sentences, so that Siegel was obliged to ask him if he wanted to quit before the second question. But what was remarkable about that interview was the bravery and self-understanding that Capote displayed. He performed almost in a trance, too tired and drugged to lie. He had said he was going to show up, and he did, even though he hadn’t slept in two days, and he tried very hard to finish the program, answering everything despite the level of some of the questions. He was cut after 17 minutes.

“My life is so strange — it’s not like anybody else’s,” he tells Siegel.

“You have had this history of alcoholism,” says Siegel.

“Oh, my God, alcoholism is the least of it. That’s the joker in the cards. My problem was never drinking. [It was] taking different kinds of drugs, but not things that other people would consider drugs.”

“But the combination of drugs and alcohol,” says Siegel.

“I put them together like some sort of cocktail … I think that anybody that starts to do that thing, you know, they get into a kind of pattern of doing. I mean, you start by doing one thing and then you start by doing another thing because you put the two things together.”

You’ve been doing it lately?” Stanley asks.

“I’ve been doing it for 20 years.”

Siegel asks why.

“I can tell you in exactly one word: anxiety.”

About what?

“I don’t know. I think certain people have a feeling of anxiety. A lot of analysts call it ‘free-floating anxiety’ … You know it doesn’t mean anything, but it’s always there, and I don’t know what it is … I know people who do fantastic things because of anxiety.”

“It began a long time ago?”

“It began because I … because my mother. It was all very simple. My mother was a very beautiful girl and only 17 years old, and she used to lock me in these rooms all the time, and I developed this fantastic anxiety that no analyst has ever been able to … “

“Unlock?” says Stanley. “Are you anxious now?”

“I’m pretty anxious about this new book of mine [Answered Prayers] … really a great sense of anxiety about it,” he says and then draws back. “On the other hand, most people who have free-floating anxiety … it really has to do with some kind of emotional relationship or something to do with their work. Well, I don’t have that at all. I couldn’t care less.” Siegel asks if he is writing now.

“Yeah, it’s almost finished,” says Truman. Later, he says, “There’s something about me that just got out of it … Somebody like me, you really never get through it really to … there’s just something that’s going through your sensibility. It just doesn’t work.”

“Is it biochemical?”

“It’s just something. It’s also the reason why you work and create and do something, but it’s an awfully high price to pay.”

Siegel asks what will happen if Capote can’t overcome his problem and says he is sure Capote has thought about it.

“Well, you know, I do fret,” says Capote, “months and months and months and my writing and everything, but the obvious answer is that eventually I’ll kill myself without meaning to.”

“Like Marilyn Monroe, for example?” asks Siegel.

“Well, you see … it’s a really interesting thing, because Monty Clift and Marilyn and I were all great friends. I don’t know what it is … a particular kind of sensibility.”

Siegel wants to know if he could reverse the process. “Well,” says Truman, “I’ve been in practically every hospital in America you can think of. I don’t know. Maybe yes, maybe no. I’m not dishonest about it.”

Friends tried to help by recommending analysts. Years ago, Jack Dunphy’s wife, Joan McCracken, told Dunphy that Truman was “very insecure.” “Who isn’t insecure?” says Dunphy. “Analysts were a waste of time and money. He’d start to duel with them, and he was always brighter.” Friends checked him in and out of Silver Hill, Riggs, Hazelden, Smithers, and various emergency rooms. When he had bad times, “he was forgiven because you always knew that in a month he’d be back in the hospital,” says a friend. He was well known to the staff of Southampton Hospital. John Scanlon, there in June of 1982 after a heart attack, remembers Truman being brought in in a straitjacket. The next morning, Scanlon looked out, and there on the misty green lawn was Capote, hiding behind a bush with his sneakers in his hand, pursued by huge female attendants. Later, he saw Capote tied to the bed, a small swollen lump with only his sunglasses showing.

“When he was drinking or on drugs, there was not much you could do,” one friend says. “Shake him. Scream at him. I tried, but when one thing stopped, another would start. He could have died a year ago or a year from now.”

“I remember sitting on his bed and saying, ‘Why are you doing this to yourself?’ ” says Kate Harrington. “Then he’d ‘fall’ twice a year. And finally, when I was 17, I said, ‘Isn’t it enough that you have me? I’d be heartbroken if you died.’ ‘Well, of course you would,’ he said.”

At one dinner in the late ’70s at Lester Persky’s apartment with two friends, Persky, a kind and true friend of Truman’s, decided to talk to him “like a Jewish mother.” For 40 minutes, he told Capote his forebodings. “The friends’ jaws fell slack. Truman took it and was very quiet. He stopped then for a few months.”

“His battle was much more difficult because of his cross-addiction to a spectacular panoply of other drugs,” wrote a man who lived with him at this time. “When the shakes became untameable through use of alcohol, he moved to downers to stop them and to sleep without the nightmares. Then, to offset the lethargy … he went to uppers. Later, cocaine was added to the already dangerous equation. First, he wanted to get truly well. In the latter stages they merely served as three-day emergency rooms. Which didn’t serve cocaine. He could get that only from his ‘friends.’

“His addiction was more difficult to treat than most, since he was what is called a ‘protected addict.’ That is, he had almost unlimited resources to acquire alcohol and other drugs … to avoid well-meaning but critical friends, as well as acquire … sycophants … who abetted his spiral to death.”

Capote knew almost too much about medicine. He had doctors all over, and since he really was sick and anxious, whenever he walked in, the prescription pads came out. When he died, the coroner found his death complicated by multiple-drug intoxication. He’d taken pills for sleep, anxiety, leg pains, and epileptic seizures. He was always bragging that he knew how much he could take. Once, he said that Sunny von Bulow had sent him a book about recreational drugs: “It describes the maximum dose you can take safely, and it was definitely accurate about every drug I’ve taken.” One day, Gerald Clarke had lunch with him at Bobby Van’s when he was waiting for a delivery of sleeping pills. He held up a new violet pill and said, “Aren’t these the most beautiful pills you’ve ever seen? They let me sleep four hours at a time, which I’ve never been able to do.”

It is, of course, presumptuous to go beyond Capote’s own words to explain why this happened. Even Jack Dunphy says he does not know. “Fame? Success?” Capote had blamed his childhood, he blamed envy, saying, “People simply cannot endure success over too long a period of time. It has to be destroyed.” Certainly, there were external events that hurt him. Some friends, like Phyllis Cerf Wagner, saw his bad times beginning in 1965 with the pain he felt at the execution of the killers of In Cold Blood. Ten years later, he was rejected by some of his social friends — in Aileen Mehle’s words, “he shot himself in the heart. He went from the pinnacle to the pits.” For, as Mailer says, he had tasted a renowned social power. “No one came near it, and he was probably prouder of that. It was harder to do than was the writing for him. His talent was his friend. His achievement was his social life.”

It hurt Capote to lose the friendship of the Paleys. He had been at their house every weekend since Babe’s daughter Amanda Burden was a girl, up until “the dread book,” as she calls it. Babe was his “Bobolink.” “He’d been her closest confidant for 18 or 20 years, part of the fabric of her life,” says Amanda. ”When she saw him later in a restaurant, he was invisible to her. Then he seemed to disappear and begin his serious drug life.” Mailer thinks that “La Côte Basque” may have been Capote’s deliberate effort to free himself. “Either I grovel at their feet, or I get down to real work,” though Judy Green says Capote told her he believed he was giving “immortality” to those he wrote about, and they would, of course, understand. Liz Smith even went so far as to suggest that Capote died of a heart broken by Lee Radziwill’s refusal to testify for him in Gore Vidal’s lawsuit five years ago, an assumption so embarrassing to Radziwill that she stayed away from his memorial because of it.

Capote’s immediate young fame, however desired, was something he always had to deal with. In lulls, the celebrity absorbed his creativity. There was always the dangerous appeal of the verge, sliding into and out of life with the Warhol people, where fame is quick as a photograph and the night rolls on and on. One of the saddest sentences ever written about Capote probably made him the happiest. “ln November of 1966, when it all came to a head, the art of the novel was 388 years old and the American system of party giving was 345,” Esquire wrote after the Black and White Ball for Kay Graham. Neither will ever be the same, and all because of one man who managed to become a master at both.”

He felt vacant, he needed a family, he had no bourgeois core, he was not hard-thinking, not intellectual enough — he’d lost his looks, his various friends would say. But does anyone really have to go beyond the vision of a writer with a book in his mind that he could not write?

“The pain was always there inside him,” says Kate Harrington. “He told me how he saw five things at once and how exhausting it was — a flooding, constantly. Others saw one or two levels, so his writing was his way of getting it out.” When he could no longer write as he wanted, he was left with what he called his “dark madness” and the remedies.

“I always felt he brought out something that made you want to hug him, and at the same time, he wanted you to be scathing,” says Kate. “Even the first time I met this sweet little man, he had something hurt. When I saw him give a lecture, he came onstage and they laughed and l thought, ‘This is what his whole life has been like.’ Maybe it’s how he became so scathing.”

Some blamed his later companions. Just as some men seem to keep marrying the same woman, Capote seemed to be trying to find Jack Dunphy again in the men — sometimes married, usually Irish — with whom he would stay for years. But there was something wrong with them and Truman together. It was said they mistreated him, made him suffer, and brought out his worst. Like Truman, they drank. Once, Capote passed out and fell from a bed he was sharing with one of them. When another man discovered Truman lying on the floor, he said. “Why didn’t you help him or call me?” The man said, “What do you want? l’m sick, too.” They were toted along now, into worlds Jack had shunned, brought to lunch with Princess Grace. It was hard for them. They “broke things” in every way.

“What is the good of being a famous novelist if you can’t have a little vanity,” says Mailer. “But he had an outrageously overweening store of it, and that’s part of what killed him.” Even after he lost the vanity in his appearance that caused him to go to diet doctors and have his face lifted, his hair, eyes, and teeth done, even after he was no longer bothering to get his clothes into eye-pulling combinations or even get fully dressed (he’d wear a seersucker suit with nothing underneath or an overcoat with underwear), he never lost his pride in his work, which may explain why Answered Prayers has never been found. It was better to read magazines.

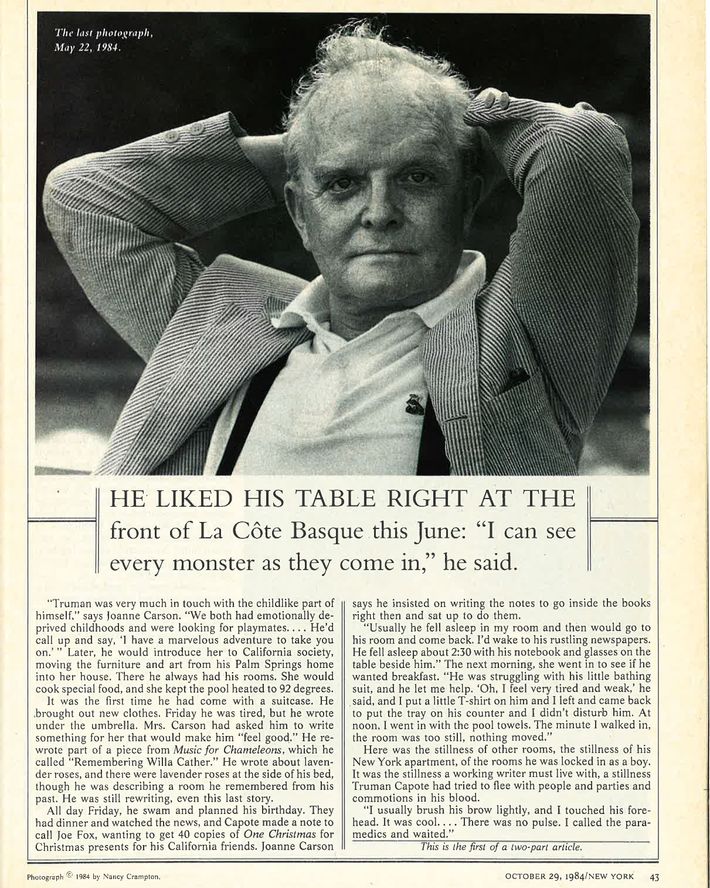

Lester Persky, who is producing the movie of Capote’s story “Handcarved Coffins,” had several lunches with him in June. With Truman’s cooperation, they made some tapes. They decided to return for one lunch to La Côte Basque. On the tape, Truman’s voice is thick and very slurred. He says he has taken a new prescription drug: “lt has a strange effect — it makes me feel dizzy.” He likes the table they have given him right in the front: “I can see every monster as they come in.” Eventually, he finds his stride and begins telling stories about Le Pavilion and a wicked tale about the Duchess of Windsor waiting for Jimmy Donahue in the arcade of El Morocco.

He spent a lot of time at the beach last summer with Jack Dunphy. “Jack was always the boy he fell in love with. Truman was so proud of everything he did,” says a friend. Kurt Vonnegut thinks Capote was trying to set up a new group of friends. “He would never have bothered with me before,” he says, and in fact, Vonnegut had the impression that Capote hadn’t read his work or that of Michael Frayn, who was also a guest at the last lunch the Vonneguts had with him, the week before he died. That day, on the way in, Capote lost his balance and seemed faint, and Frayn and Vonnegut supported him. During lunch, he talked all about himself, telling his stories, but then he fell bad again and lay down on a chaise. Vonnegut drove him home, but Capote was insistent about being let off at the end of his driveway, even though it was painful to walk. An arrest for drunken driving the previous summer had changed his life. He was no longer seen barreling along Daniels Lane in his maroon convertible, so small behind the steering wheel that a friend called him the Headless Horseman and those who knew the car would quickly pull over to the side of the road.

He was deprived of his routines of Bobby Van’s and had to swim in the ocean since he could no longer get to pools by himself. In some ways in his later life, he had become like John Cheever’s Neddy in ”The Swimmer,” going from pool to pool wherever he lived, drinking and swimming, not quite realizing what had happened to him. Always, at a pool, he would go to the edge and walk right in without looking. At last he was too sick to swim, and the pool he liked was sold to strangers.

The week before he died, in August, Capote met Kate Harrington for lunch. He was not feeling well. He did not want to go back and stay alone in his apartment. It was soundproof and even friends felt the silence. This was one of the many lunches Truman would have where he seemed to want it to fill his afternoon, but Kate had to return to work at Interview. Later, he spent the night at her place. She had her friends over, and he amused them all with stories, sitting in bed, enchanting a fresh group.

The next week, Kate and Lester Persky had two dinners with Capote. After one, a friend of Kate’s took him home and Truman told him that he could finally let Kate go because he knew she would be all right. During these last dinners, he said he was excited about the movie of “Handcarved Coffins.” He talked about Los Angeles, saying, “Who wants to live in a town where the leading social figure is a bald nearsighted dwarf?” But still, says Persky, he had an “idée fixe” about getting to California. He felt comfortable at the Jockey Club and was munching a huge amount of caviar. ‘I love caviar. but it’s no fun unless you order a pound,” Truman said. And he talked a bit about his birthday and a party he would give here, maybe a small one, for 20.

“He would always say, ‘I’m coming back in two weeks,’ even when he stayed months,” says Kate. “This time, he looked at me through his blue-tinted glasses, and I said, ‘When will I see you?’ and he said, ‘I don’t know when. But you do what I told you to do. I know about these things. All right, baby doll?’”

He was anxious to come to California,” says Joanne Carson, his friend for 20 years. He’d always arrive with a round-trip ticket, but he told her to make the reservations just one way. “I don’t know how long I will stay,” he said. He kept calling, wanting to move up the trip, but she told him she was working. “Someone who loves someone like me has to be available at all times,” Capote had once said, but now his women worked, like Kate, even C. Z. They weren’t those women of fashion who would cancel anything to be with him. It was almost as though there were less room for him in his world.

”Truman was very much in touch with the childlike part of himself,” says Joanne Carson. “We both had emotionally deprived childhoods and were looking for playmates … He’d call up and say, ‘I have a marvelous adventure to take you on.’” Later, he would introduce her to California society, moving the furniture and art from his Palm Springs home into her house. There he always had his rooms. She would cook special food, and she kept the pool heated to 92 degrees.

It was the first time he had come with a suitcase. He brought out new clothes. Friday he was tired, but he wrote under the umbrella. Mrs. Carson had asked him to write something for her that would make him “feel good.” He rewrote part of a piece from Music for Chameleons, which he called “Remembering Willa Cather.” He wrote about lavender roses, and there were lavender roses at the side of his bed, though he was describing a room he remembered from his past. He was still rewriting, even this last story.

All day Friday, he swam and planned his birthday. They had dinner and watched the news, and Capote made a note to call Joe Fox, wanting to get 40 copies of One Christmas for Christmas presents for his California friends. Joanne Carson says he insisted on writing the notes to go inside the books right then and sat up to do them.

“Usually he fell asleep in my room and then would go to his room and come back. I’d wake to his rustling newspapers. He fell asleep about 2:30 with his notebook and glasses on the table beside him.” The next morning, she went in to see if he wanted breakfast. “He was struggling with his little bathing suit, and he let me help. ‘Oh, I feel very tired and weak,’ he said, and I put a little T-shirt on him and I left and came back to put the tray on his counter and l didn’t disturb him. At noon, I went in with the pool towels. The minute I walked in, the room was too still, nothing moved.”

Here was the stillness of other rooms, the stillness of his New York apartment. of the rooms he was locked in as a boy. It was the stillness a working writer must live with, a stillness Truman Capote had tried to flee with people and parties and commotions in his blood.

“I usually brush his brow lightly, and I touched his forehead. It was cool … There was no pulse. I called the paramedics and waited.”

Part II: The Magical Drape

The missing chapters of Truman Capote’s Answered Prayers are a new form of fiction — the almost-written novel. They exist in a limbo state not quite here or there. Call it spectral fiction. Call it spoken fiction. Capote could and did recite parts from memory, they were so fixed in his mind. He felt them. At one time, he may even have written them down, but he would never send them forth. He couldn’t get them or let them out. Certainly, a plan for Answered Prayers exists (Capote’s metaphor for it is a gun), the characters exist, the stories exist, the dedication exists, the epigraphs exist, all in the ghostly state of an unborn work that hung around too long, growing into Capote’s own spoiled monster.

At the very end of his life, Capote didn’t even keep up the fiction with some people that he was writing Answered Prayers. He went out to California with his new pants from Shep Miller’s boys’ department, but Joanne Carson says he brought no papers with him.

“How are you comin’ with your writing, Truman?” his estranged aunt Marie Rudisill asked him in a “making up” conversation six weeks before he died.

“I’m not writing anything now,” he told her, and when she asked about Answered Prayers, “Oh, I destroyed that,” he said. And she imagined him “like a child in a spasm,” tearing pages into little tiny bits the way she had seen him do so many times when he was a boy. Though the novel seemed so almost-there real that it fooled his closest friends and still scared the social world, by that time there was probably nothing to destroy.

Truman would have got $1 million if he had finished Answered Prayers and Random House had accepted it. If he merely had said that he never would finish it, he would have got around $300,000. “He wanted the money, but he had a lot of pride,” says his editor, Joe Fox.

Last summer, Truman Capote said he wanted to return in his writing to his past and the South. Six years ago, he had told his friend Donald Windham that he just didn’t want to be a writer anymore (Windham describes this conversation in his excellent privately printed book, Footnote to a Friendship). In June, he said he was working on “a novel” and wanted to publish selected parts of his diaries. He would go back to 1933, when he started writing in his Red Cheek Indian notebooks, and jump around in time. He told his aunt he wanted to write a memoir of Monroeville.

Sometimes Truman Capote lied. He was a deft liar. As he told Donald Windham, “I remember things the way they should have been.”

He was an actor. He was a salesman. He was a showman like his father, Arch Persons, who once on a tour through the South toted around an Egyptian named Hadjah, whom he buried alive and then “resurrected” from the dead.

“Truman put a magical drape over his life,” his aunt says. “He was a foxy person. He could make you believe black was white. He could make a worm stand on its tail if he wanted.”

There were people he could lie to who would not know he was lying and those who would know and let it pass and the vast bulk of a public who would not care as long as he made them smile and he wrote it well. He lied with love to give people pleasure, and sometimes to give himself power.

He told two kinds of lies. The life lies and the art lies. They both sounded good. And they both read so well.

Certainly, throughout his life he suffered more than he made anyone suffer. In the end, his own excuses may have been lies. He said his mother threw him from a train window and locked him in rooms. “He might have locked his mother in rooms,” says his aunt. “He was the whole core of the whole family. He was spoiled to death. He was smothered with love.” But not by his mother. She rejected him, and maybe she was all that mattered. At times, Truman was a “little tyrant. If he loved, he wanted someone completely.”

Marie Rudisill’s book, Truman Capote, presents a marvelous picture of Truman and Nelle Harper Lee, the pretty boy and the tomboyish girl, memorizing the longest words in the dictionary, two children from a town of 900, cutting dream pictures from magazines to paste on their kites. “Truman stayed with the grown-up people,” she says. He was never a child until later, when he was never quite an adult.

He had his mother’s early wildness (which he gave to Holly Golightly), and later her desire to get out of town and head for the life of the city, where the top people were waiting. In the way she left the Creek Indian lover who made her happy but always kept him in the background of her life, Truman and Jack Dunphy were often physically separated. Dunphy loved him but didn’t live in his world. He did his own writing and went off to ski. Both Truman and his mother separated from people who might have made them happy and went to look for more.

Answered Prayers has all the uneasy history of a work that had been around too long and never would be finished. Capote had the title since the 1950s. He told his biographer, Gerald Clarke, that he began in 1958 with notes, a full outline, and an ending. Leo Lerman remembers him talking about a Proustian work then. In 1966, he returned to it, signing his Random House contract. He started to “talk it up as the contemporary answer to Remembrance of Things Past,” says an editor. There was always the promise of great length. In 1968, he sold Twentieth Century Fox a two-page treatment for $200,000, but when Capote took so long to write the novel, Fox got concerned and returned the rights to Truman, who returned the money. In the ’60s, he tried to sell parts of it to Vogue. In 1972, he claimed it was two-thirds finished, but nothing appeared until Esquire published in 1975, much to the annoyance of the editors at Random House, who felt he had released too much too soon. Before he died, in 1971, Bennett Cerf read parts of it in Palm Springs and thought it was “a masterpiece.” “I always planned this book as being my principal work, the thing I always have been working towards,” Capote told Clarke. Truman said that when he was in the middle, in 1977, he had a “nervous breakdown.” Then, supposedly, came the period of rewriting.

In 1973, two years before the first Esquire chapters, Lenore Hershey, who had just become editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal, heard Truman was having difficulty with Answered Prayers. She went out to see him on the island and asked him to do a piece for the Journal that would be quick and easy for him. She wanted him to write “Blind Items” (true stories with fake names), and she would pay him $50,000 for two parts. Thus, the Journal would get the stories she had heard Truman tell her over lunch. Wicked stories, because he always had loved to shock. To see a stewardess’s face when he ordered “cyanide on the rocks,” to go around a table and tell everyone what sort of plastic surgery each ought to have, to tell university students who had picked him up for a lecture stories of why X really stabbed his wife, why Mrs. Y married rich Mr. Z (because she was in love with Mrs. Q and wanted to have as much money as her friend), stories full of buggery and incest and names that couldn’t have meant anything to them.

Mrs. Hershey ran the first set of Blind Items (including the story of the dog jumping out the window, the story of the man marrying the woman he had had an affair with years before, having forgotten his accountant had been sending her checks for the last 30 years) in her first issue of the Journal, in January 1974. She found the second set “so terrible, scurrilous, and dirty” that she never printed them. These stories became the heart of “La Cote Basque 1965.” If she had used them, Capote’s social life would have been ruined a year earlier.

With this second set of Blind Items, Capote included a handwritten note identifying the people in the stories: an industrialist, a governor’s ex-wife, Merle Oberon, Kim Novak, Sammy Davis Jr., Mrs. William Woodward Sr., Mrs. William Woodward Jr., a publishing tycoon, his ex-wife. Two years ago, he remembered he had given Mrs. Hershey his manuscript and called her when he was “drunk and confused,” asking if she still had them.

In this set of items, he told five stories, four of which appear in “La Côte Basque 1965,” two at length.

1. The Airplane Story: A “clever, not too couth, dyed-blonde with scarcely exorcised Brooklyn linguistic habits” makes a list of the world’s “most (powerful) available men,” chooses one, and sets out to meet him by booking herself a seat next to him on a flight he takes every week. She tries to vamp him, waits two weeks, books the same seat, and says, “This can’t be coincidence. Fate, perhaps?” He marries her, backs her publishing venture, which fails. The marriage is bad. Finally, she says to him, “What’s the matter with you?” and he answers, “Nothing that a divorce from you wouldn’t cure.” This exchange takes place between Lady Ina Coolbirth and her husband in “La Côte Basque 1965.”

2. Washing Up: “A captain of industry” lusts after a governor’s ugly wife. During a dinner party, he slips off his pumps and “starts massaging with his silken-socked feet her fulsome tootsies, her ostrich-tough calves.” He invites her to his apartment in a New York hotel, they go to bed. She is very careful about keeping the lights out. She bloodies the sheet. Because his wife is due back the next morning, he washes the sheet. He scrubs and scrubs, stuffs the sheet in the oven, irons it, and pretends to be sleeping when his wife appears at seven. “My darling, I didn’t want to wake you. You looked so exhaustedly sweet. So am going straight to Greenwich,” she writes in her note to him.

3. Mr. Bojangles: A black entertainer blind in one eye falls in love with a blonde movie star. Her studio head, Harry, sends hit men to Vegas. “Mr. Bojangles, you’ve got one eye now — how’d you like to try for none?” Soon after, he marries “another vanilla number.” This story, with the names of Sammy Davis, Harry Cohn, and Kim Novak used, appears as a parenthesis in “La Côte Basque.”

4. Temperature: A 66-year-old ex-film star with three face-lifts by “increasingly cunning surgeons,” who lives only on steak, oysters, and white wine, has a very successful sex career. “But what has Pearl got? … And it isn’t her fame, her beauty, her Swiss bank account. It’s her temperature.’ She runs a permanent temperature of 104 degrees. “It seems to do her no harm, and her lovers all roll their eyes and swear there is no sensation quite so unique as being melted by this particular oven.” This story is not in “La Côte Basque.” Probably Capote was saving it for his Hollywood chapter.

5. Mrs. Willows’s Dinner Party: An octogenarian grande dame who lives in “pre–World War One style’ in an East Sixties townhouse gives a dinner party every November for her daughter-in-law, “the well-known murderess, Mrs. Peter B. [Mary) Willows.” Peter Willows is a 19-year-old sailor, a virgin; she is a chorus girl who gets him to marry her five days after they meet. The family disapproves, but she gets pregnant, and once her son is born, the mother accepts her, teaches her many small graces, and even gives her “a reading list of some 50 books.” Peter falls in love with his second cousin and asks for a divorce. Mary agrees if he will give her $5 million, but he hires a private detective who finds out Mary is having an affair with a cop and turns up the fact that she is still married to another man. Peter confronts her. Then she invents a prowler, sends the servants and children away. They return from a party, he showers, she screams for help. She shoots him and calls her lawyer. Mrs. Willows Sr. covers it up for the sake of the children. Mary goes to live in Europe, returning only for the annual party. “But what everyone wonders — well, in those minutes when they are alone together before the first guests arrive, what do these two woman [sic] say to each other?” And this, of course, is the centerpiece of “La Côte Basque” — set off by the appearance of Ann Hopkins and her priest, retold brilliantly, with some facts changed. This is the story that was blamed for leading to Ann Woodward’s suicide. Her closest friends say she was already very depressed, and then she read it.

The fact that Capote was willing to publish these stories in 1974 in the Journal tells something about his motives. It is one thing to sacrifice your friends on the altar of literature, as he always said, quite another to tell the same stories rather sloppily in the Ladies’ Home Journal. “My whole point was to prove gossip can be literature,” he said to Liz Smith in this magazine’s issue of February 9, 1976. Perhaps, as Norman Mailer has suggested, he was trying to change his life to get to work, and wanted to do it as quickly and deliberately as he could.

These Blind Items are crude, roughly written, and full of signs of haste. To read them alongside “La Côte Basque” is to see what he told his friend Judy Green: “Good writing is rewriting.” And rewriting. And rewriting again. Even “La Côte Basque” itself is uneven in quality, part dazzling and viciously funny, part sloppy and a betrayal of his best work. Capote, who could describe Roederer Cristal Champagne as “bottled in a natural-colored glass that displays its pale blaze, a chilled fire of such prickly dryness that, swallowed, seems not to have been swallowed at all, but instead to have turned to vapors on the tongue and burned there to one damp sweet ash,” could, a few paragraphs.earlier, use as cheap a phrase as “hotshot Hollywood hottentot.”

In the year between the Journal and the Esquire chapters, he must have done a lot of rewriting. In “La Côte Basque,” the Washing Up story is prefaced by Ina Coolbirth’s saying, “Would you care to hear a truly vile story? Really vomitous? Then look to your left. That sow sitting next to Betsy Whitney.” In this retelling, he introduces language, drama, details, and analysis (“It was simply that for Dill she was the living incorporation of everything denied him, forbidden to him as a Jew, no matter how stylishly beguiling and rich he might be: the Racquet Club, Le Jockey … ”), reshaping his material and refiltering it through his perfect eye and ear.

Here is the difference in just two passages. First, from the Blind Items: “Swiftly, he stripped the bed and carried the offending sheet into the bathroom, where he filled the tub with hot water, dropped the sheet into it, got down on his hands and knees and began to scrub. He scrubbed and scrubbed. Then he drained the tub and scrubbed some more. Hours went by. The bathroom was like a sauna, the sweat pouring off him, and, trying to see the shinier side, Sam thought: well, at least it’s good for the figure.’ This is from “La Côte Basque”: [He] started searching in the kitchen for a box of laundry soap, but he couldn’t find any and in the end had to use a bar of Guerlain’s Fleurs des Alpes. To wash the sheets. He soaked them in the tub in scalding water. Scrubbed and scrubbed. Rinsed and scrubadubdubbed. There he was, the powerful Mr. Dillon, down on his knees and flogging away like a Spanish peasant at the side of a stream. It was five o’clock, it was six, the sweat poured off him, he felt as if he were trapped in a sauna; he said the next day when he weighed himself he’d lost eleven pounds.”

This story was widely reported to have cost him the friendship of Babe and William Paley. The apartment and other details in the story reminded people of the Paleys. He called his character Dill (Harper Lee’s name for Truman in To Kill a Mockingbird), which, perhaps, shows his desire to identify himself with him. And yet the man Capote named to Mrs. Hershey as having been the man in the original Blind Item was not William Paley.

As he wrote about his childhood in his early work, so he used his European years and his New York life, which quite deliberately were “social,” in Answered Prayers. When Bennett Cerf became concerned early on that Capote had begun hanging around too much with the women Phyllis Cerf had introduced him to, Capote said to him, “It’s my research. I’m going to write about them.” And he did. The haunting, precocious children, the smells and sights and tastes of the rural South were replaced. The Aunt Sooks began to wear Mainbocher, and the gentle rhythms of southern speech gave way to these ladies who talked like bitter drinking broads. There was nothing of beauty left in his world. “The strengths of his early stories were the very sensitive characters,” says Walker Cowen of the University of Virginia Press. “There was a day and night world in the Capote universe. Bad night dreams versus daylight freedom and happiness.” Now the night vision and the bad corrupting dreams began to take over. P.B. Jones, who had a lot of Truman in him, was a male whore, a masseur, a failed writer. There were no gentle women. A curtain was drawn back onto a room full of grinning monsters. There were some good people in Capote’s rooms, but he left them out; this brutalizing view lacks authenticity.

In his personal life, Capote was never satisfied by the private world of intellectual homosexual couples living together in lifelong friendships as devoted as his and Jack’s. But these were men who knew and valued his work. This parallel but separate society existed so much apart that one friend, who knew him for 35 years, could write that never once had he been invited to the same party as Truman. Neither was he satisfied by the company of academics, critics, and other writers. He had given most of them up in his early 20s.

Capote always had to have the other — “real” society, even café society. He was jealous of his unique position in it. Norman Mailer remembers coming upon him once at a small dinner, and Truman looked at him as though he thought, “How dare I travel in his circles, move onto his patch. It was almost comic.” After all, he was a Park Avenue boy who went to Trinity, graduated from Franklin. (When it suited him, he was a poor boy; when it suited him, he was rich, and he did bounce back and forth from Park Avenue to Alabama, from Europe to Kansas.) For a time, he replaced both societies with the Warhol group, where the homosexual and the “real” societies merged. And all along he took on as pseudo-families the real families of his married lovers.

Truman wrote about his early social friends in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “The two main characters were identifiable to those who knew them. His creativity switched them,” says Phyllis Cerf Wagner. “He borrowed heavily from their speech patterns. He rewrote and rewrote, trying to make them less identifiable.” But friends saw Carol Matthau in Holly and Gloria Vanderbilt in Mag Wildwood. They knew “Golightly” from the Golightly bookstore on Washington Square and that his visits to his stepfather, Joe Capote, in jail were reflected in Holly’s visits to Sally Tomato.

One never says a quarter of what one knows. Otherwise, all would collapse. How little one says, and they are already screaming,” Camus wrote. A year and a half ago when Capote was talking about Answered Prayers being finished, he selected this as one of the two epigraphs for the book and gave it to Joe Petrocik. The screaming had begun after “La Côte Basque.” It was the most expensive thing he ever did. The ice curtain fell. Most invitations stopped, his calls weren’t taken, friends ostentatiously changed their tables when he appeared in restaurants. He was surprised by their “hard-hearted reaction.” He told Judy Green Answered Prayers was better than Proust because he was more accurate. He didn’t intend to disguise his characters. “If [Proust] had been absolutely factual, it would have been less believable, but … better,” he wrote in Answered Prayers. But he wasn’t more accurate. First, he was blamed for telling the stories, and finally, he was blamed for not telling them right. He had recognizable people doing abominable and ridiculous things, pinioned in their moments of folly, but he got it wrong. There was a vicious tilt, whole lives expressed by the worst things that were done. “There was only a skein of truth,” says Aileen Mehle. How could his character wash out blood in hot water? a female writer complained. But this was fiction. All his claims of truth hurt him at last. A little germ grew into an elaborate anecdote with changed names but glaring faces as all his art and all his attempts to protect his people went awry. It was fiction with dangerous overlaps, real names mixed with false, real conversations with stories heightened for effect and changed for the drama, time telescoped. Last June, he told a friend he had based “La Côte Basque 1965” on several luncheons over a period from 1953 to ’54. At one, he had seen Cole Porter sitting with his legs flung over a chair because he was in pain. He said that Slim Keith’s reaction had surprised him the most, because she was not the person in the chapter (Lady Ina Coolbirth) and he had described the person who was in fact her worst enemy.

In the drunken hour of 3 a.m., Capote lay on a motel-room bed, sobbing about the Paleys’ desertion, in front of a national reporter, and yet he posed sharpening his nails with a stiletto for Esquire’s cover. It was part of the monster fame that was as much his addiction as anything else, a fame that grew until people on the streets who never read him could imitate his tiny whine. He ran after his fame. It was obvious in the way he choreographed all his press to come out within the first two weeks of his books, in the artful way he worked with photographers (he is probably the most photographed writer of this era). With his gift for immediate intimacy, he was more than kind to writers and photographers he liked, signing notes to them with his special name, “Namurt Etopack,” offering them a drink of vodka, whiskey, gin, brandy with a cherry on top, which he called “A Day in Louisiana,” calling them promptly to thank them, helping them write their books, showing them through the homes crammed with his treasures — his collections of snakes, paperweights, and, especially, butterflies. At first, long ago, he had fame for the right reasons — his work and then for his charm and outrageousness on talk shows. His last was the sad fame of collapses and the grim interest in his decline as he went “traveling in the blue,” as he once called it, when no grapefruit juice passed his lips without Stolichnaya in it. He was lost someplace between his motto, “I aspire,” and the line he said he would choose for his tombstone, “I tried to get out of it, but I couldn’t.”

There is still an abiding allure in what might have been in the missing chapters of Answered Prayers: “Yachts and Things,” “A Severe Insult to the Brain,” “The Nigger Queen Kosher Café.” In offering his Hollywood chapter to Clay Felker at Esquire, Capote had described it. It takes place in Kate McCloud’s bedroom at 550 Park Avenue. Kate and her lover, whom Truman named to Felker, are making love, and she answers the phone. Without stopping as they assume different oral positions, she has a long conversation with a “Zipkin-like figure” (these are Felker’s words, Capote was more specific) calling from Beverly Hills. In this 98-page chapter, which may actually have been written at one time, he told all the Hollywood gossip he had been collecting for years. It ends with the suicide of fashion editor Margaret Case. Kate sees her, some say dressed in a raincoat, falling past her window. Capote asked $30,000 for the piece, but he never gave it to Felker, eventually saying there was some confusion as to who owned the rights. (Random House owned first-serial rights.) He also told Joe Petrocik about “A Severe Insult to the Brain” (this is what it said on Dylan Thomas’s death certificate.) Petrocik says Capote began to read it one night in his apartment, but it was hard to tell if he was really reading or ad-libbing something he had rehearsed. Petrocik says, “I never saw one line written on a page.” Capote’s friend Kate Harrington read bits and pieces of this. She remembers a description of the A and B sets of Hollywood, Audrey Wilder at a dinner party, the Temperature story, stories about the Reagans and various parties. Harry Benson, whom Capote called his favorite photographer, also heard him read a bit in which he “described Jerry Zipkin as a commode.”

In one Esquire chapter, Capote describes the Nigger Queen Kosher Cafe. Once he told Interview, “The narrator in the story decides that in the abstract sense, the Valhalla or the grass-is-greener place that he wants to go is an imaginary café … a kind of mental Studio 54.” Esquire, in a note accompanying “Kate McCloud,” said that the final episode of the novel was supposed to be a crime the narrator, P.B. Jones, would commit for Kate McCloud, presumably the kidnapping of her son.

Some believe Kate McCloud to be based in part on a current social figure, now in her 60s, and also on Mona Williams Bismarck. Capote always hinted that she was from another era, and Mona, who died in 1983, was 86. Like Kate, the daughter of a head groom, she was the daughter of a stable hand who married the owner of the estate when she was 18 and he was 37. (Kate’s first husband is 22 and she is just 16 when they marry.) Mona had emerald-green eyes. Of Kate, Capote wrote, “Again there are green eyes, and then there are green eyes … Like Mrs. Grant’s emeralds.” Mona was the best-dressed, most social figure of her era. Her first husband got custody of her child. Her third husband was the immensely rich Harrison Williams. How like Capote it was to have listed her among “the swans of our century” in Answered Prayers. He always played little jokes in his work — he even had his narrator, P.B. Jones, as the author of a work called Answered Prayers and Other Stories, the theme of which was “people achieving desperate aim only to have it rebound upon them — accentuating, and accelerating, their desperation.”

On a scrap of paper Capote had left at Petrocik and Clements’s house (he told them he was dedicating Answered Prayers to them), Capote wrote:

Unspoiled Monsters (handle)

A Severe Insult to the Brain (trigger telephone)

Yachts and Things (barrel)

The Nigger Queen Kosher Café(bullet)

It was a gun that would never fire. This outline does not mention “Kate McCloud” or ”La Côte Basque 1965.” Capote told Don Erickson, who was then the editor of Esquire, his plan for the novel during one lunch at The Four Seasons, but though Erickson can remember where they sat, since Truman didn’t like his table and switched, he has forgotten Capote’s plan. “It seemed to be a work in progress,” he says.

In addition to Capote’s fears of completion (he said he feared he would die once Answered Prayers was done), his desire simply not to write, his problems with his companions, his bad health, his drinking and drugs, he had obvious problems with the structure of the work itself. The chapters of Answered Prayers could be pulled out almost at random and rearranged, and he said his work needed to be “held together by a narrative line.” Capote compared reading Answered Prayers to walking through an aquarium with round windows and scenes inside each one. Certain fish would swim from one window to the next. He continued this fish metaphor in the second epigraph he chose: “To be captured: the price of being beautiful. Tropical fish go on long journeys only to wind up in a tank.” (Marianne Moore.) Capote said writing his chapters was like making stained-glass windows that had to be put in place. At another time, Answered Prayers was like a wheel with a dozen spokes “all pointing in different directions.” Certainly, they seemed to be self-contained like the perfect short works he wrote before and after In Cold Blood.

He also had problems with the style he would use. This he wrote about taking three pages to achieve an effect that he could get in one paragraph using the “swift simplicity” of his “new style.” Phyllis Cerf saw him through draft after draft of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and all this is reflected in the transformation of the Blind Items into “La Côte Basque.”

Finally, there was the problem of getting it done. Out into the ether. He was hampered. It was evident from what he produced that it was hard for him now to write anything long and sustained, like In Cold Blood. It was timing too. He was prepared to write Answered Prayers before his research for In Cold Blood took him too far. He had lived the research and was ready to write the book he described to John Malcolm Brinnin as a “book that will rattle teeth like The Origin of Species.” He is said to have used cocaine to get himself writing again in the early ‘80s. He told someone he took it in “controlled amounts” to keep himself alert and offset the effects of sleeping pills. A doctor to whom he read his cocaine writing found it to be “gibberish.” Capote kept his cocaine in a hollowed-out Bible on the top of his toilet. At first, it may have been a tool to get him going, as the writing exercises had been; later it became something else. Once, borrowing a Hemingway idea, he advised a magazine writer how to work on her novel, telling her to quit in the middle of a thought, at a point where she could start the next day, to make sure “there was enough gas in the car so it would start up.”

Since no one could take care of Truman Capote, who was clearly in a precarious condition and going down, why didn’t they take better care of his work? Lester Persky says he has parts of Answered Prayers in a black notebook that Truman had asked him to copy, but he can’t find it. Fox says a year or six months after the last Esquire chapter, Capote gave him another excerpt, “30 or 40 or 50 pages,” but he can’t remember what was in it, and apparently did not even Xerox it, though he had it for “a year or two, maybe three.” Capote took it back to make revisions. It was never seen again.

Capote’s last conversation with his aunt (first reported by Ron Wenzell in the South Carolina newspaper The State) took place because she had written him saying she was 73 and wanted to make up before she died. Their estrangement, after her book, “preyed on my mind.” He called one night at 12:30. “He always called late, never called at a human hour,” and

told her he knew what she was going through with her book about his boyhood, which had caused her family and friends to stop talking to her. Finally, she wanted to destroy every copy.

“I’ve been through that,” he said. “It caused me more unhappiness. I lost every friend I ever had,” he said to her. “Truman cared,” she says. “He had that little air that he didn’t, but he did.”

He told her he was trying to start a new life, he wanted to shake off some people and unshackle himself. I’m bored with most of them, he said, and I think they’re getting tired of me.

Mrs. Rudisill thinks his last written sentences, describing lavender roses, were the beginning of his book on Monroeville. He was going back to the big white house with the bone fence and its “old timey roses.” Paige Rense, editor of Architectural Digest, thinks they were the beginning of an article, a reminiscence of Willa Cather, that Capote owed her and had said was three-quarters finished. Joanne Carson claims he was doing the story about Willa Cather as a present for her. The magical drape prevailed. Truman Capote wrote his last words and left everyone guessing.