The History of the Black Arts Movement

In the light of the recent emergence (or rather, enactment) of a novel social contract called “post-identity”, seen as a way of recognizing the value and potential of cultural diversity, we are going to talk about The Black Arts Movement, one of the most influential art groups from the 20th century.

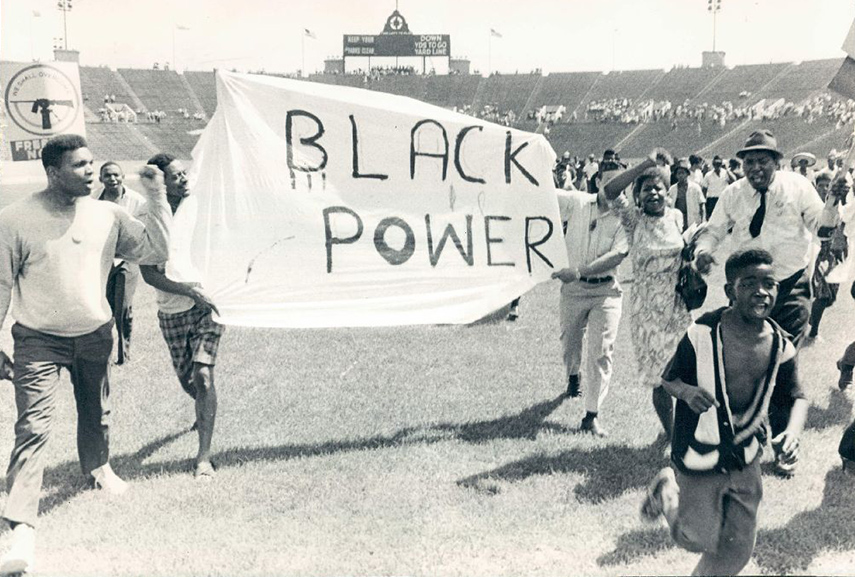

As part of a greater ideological movement called the Black Power, the African-American artists, poets, speakers, musicians and activists were joined in the wish to define the identity of Black people in America, and to resurge the Black Aesthetic, equally informed by the African tradition and the more recently established ideology influenced by the then-contemporary American life.

But before we proceed discussing the general atmosphere that the men and women of African descent had experienced in the 60’s, we must briefly touch upon the history of Black people in America, which will help explain the immense historical importance of the Black Arts Movement.

The Historical Context

Back in the 17th century, the American slave holders tried to distance the enslaved black people from their African heritage and tradition in order to secure their own authoritative positions and to maintain power. The suppression of collective identity was seen as one of the most efficient means of control, and so it was vastly exercised at that time.

Furthermore, and mostly due to similar reasons, the African-Americans had either limited rights or no right at all to get educated properly. However, despite all this, the restrictions didn’t make the slaves forget about African culture.

On the contrary, they rendered the overlap of two cultures, the African and the American, all the more authentic. For African-American slaves, storytelling became a way of passing on the tradition and knowledge, which eventually gave birth to oral culture as an idiosyncrasy that characterized Black tradition, and remains present as a significant motive to this day[1].

The Power of Words

The potency of the spoken word is what inspired generations of black people to engage in arts and to express themselves through performance, poetry and speech. It might even be said that the limited options that the enslaved Black people had in the past helped them develop certain verbal and artistic skills and master them.

It is not a coincidence that both in the 1920's and the 1960's two significant Black cultural movements emerged mostly with help from language, interactive performance and verbal expression. Still, it should be noted that even though only two specific groups were formally articulated into actual cultural movements, the oral tradition was present throughout the past centuries and it can be seen as an important part of the Black culture in general, regardless of any particular historical context. Verbal and vocal interaction was (and to a certain extent, remains) both a tool and a symbol of Black people in America.

Black Art History - The Renaissance

The first of the two aforesaid movements, Harlem Renaissance from the 1920's, was an important step in the way towards cultural recognition and independence, having introduced jazz, blues and swing to the American popular culture. It was also a period in which Black literature was officially being published, although the poets were mostly “on the leash of white patrons and publishing houses”.

Thus, the emergence of the second Black renaissance seemed inevitable, and the 1960's finally saw the rise of such movement. Many would agree that the assassination of Malcolm X, the African-American human rights leader (albeit a quite controversial activist), was the key point in the sequence of events that led up to the inauguration of the movement.

However, it is very likely that this kind of organization would have taken place either way, since the atmosphere induced by the Civil Rights Movement, protest poetry and socially engaged Black literature was already pro-revolutionary by itself.

The Black Arts Movement

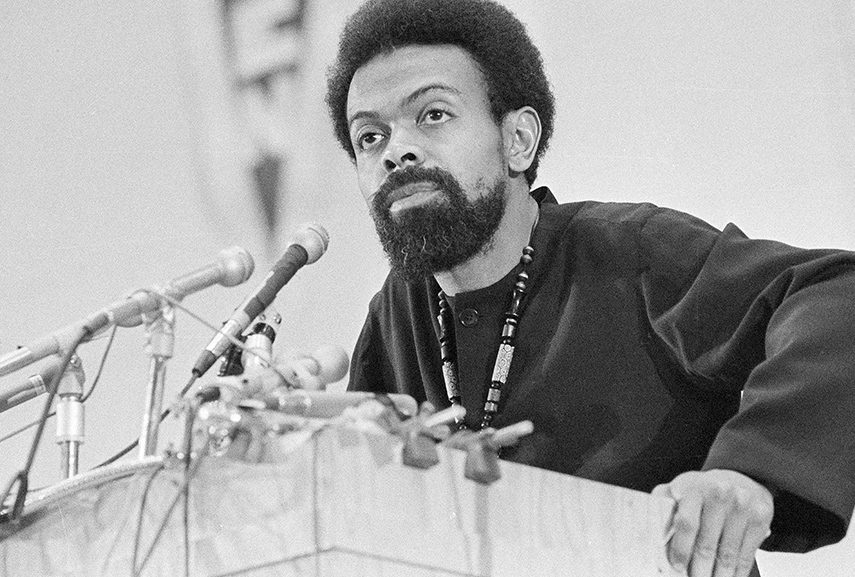

In March of 1965, less than a month after the death of Malcolm X, a praised African American poet LeRoi Jones (better known as Imamu Amiri Baraka) moved away from his home in Manhattan to start something new in Harlem. This event, equally symbolic in a geo-political context and for Baraka personally, is remarked as the moment in which the movement was born.

Soon after that, Jones founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre / School (BARTS) which became the most important institution of the Black Arts Movement at the time – not as much because of its own history, since it was quite short lived (Baraka moved away from Harlem by the end of the year), but mostly because of its formative influence, the example it had been giving.

However, for the majority of African American poets and writers, it was the 1962 Umbra Workshop that gave impetus to the Black Arts as a literary movement. The group consisted of young Black authors, mostly writers and musicians, with a few members who were involved in visual arts as well. It was based in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, which is where Baraka used to live before he decided to start BARTS in Harlem.

Defining the Black Arts - Theater Groups and Journals

Mainly, the key roles were played by Black theaters and journals that began operating independently, if not differently, from the system established by the white society. Beside its initial purpose as a home for performance, dance, music and drama, the Black theater was used perpetually as a place for lectures, talks, film screenings, meetings and panel discussions. More importantly, it kept the spirit of a productive, activist cultural centre, as opposed to other theatres (black or white), which were either vastly commercialized or restrictive, primarily focused on high art. Its main goal was to expose, as Baraka had suggested in one of his essays from this period.[2]

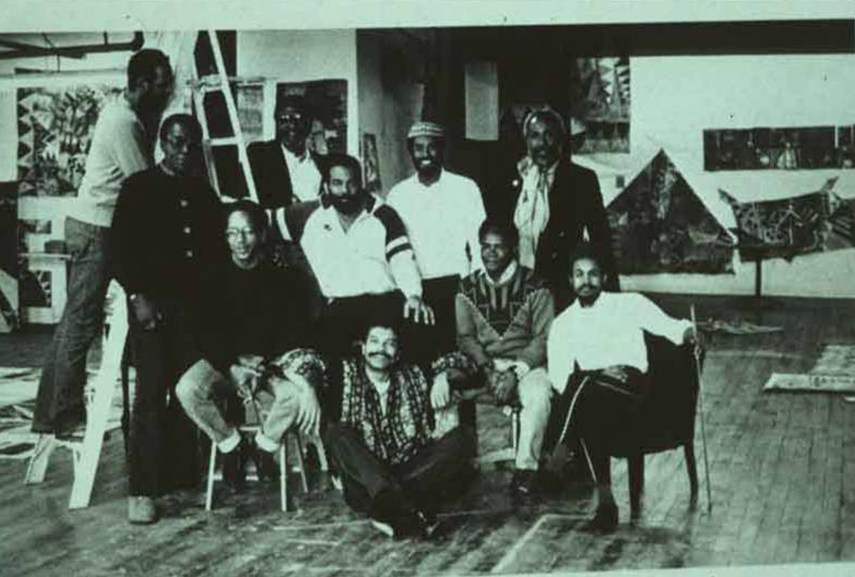

Black theatres were opening all across the United States - in New York, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, San Francisco, etc. Some of the most famous ones include The New Lafayette Theatre and Barbara Ann Teer's National Black Theatre from New York and The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) that was situated in Chicago. OBAC attracted visual artist groups as well, whose work inspired mural movements and reportedly influenced the inauguration of Afri Cobra - the African Commune of Bad, Revolutionary Artists.

However, all that was achieved in theatres wouldn't have been as influential had there not been the magazines and journals that popularized Black literature and made it known by the public. The most important magazine to publish Black literature was Negro Digest / Black World, a journal that became famous for high-quality publication content, as it included fiction, poetry, drama, criticism and theoretical articles as well.

Notable Black Artists

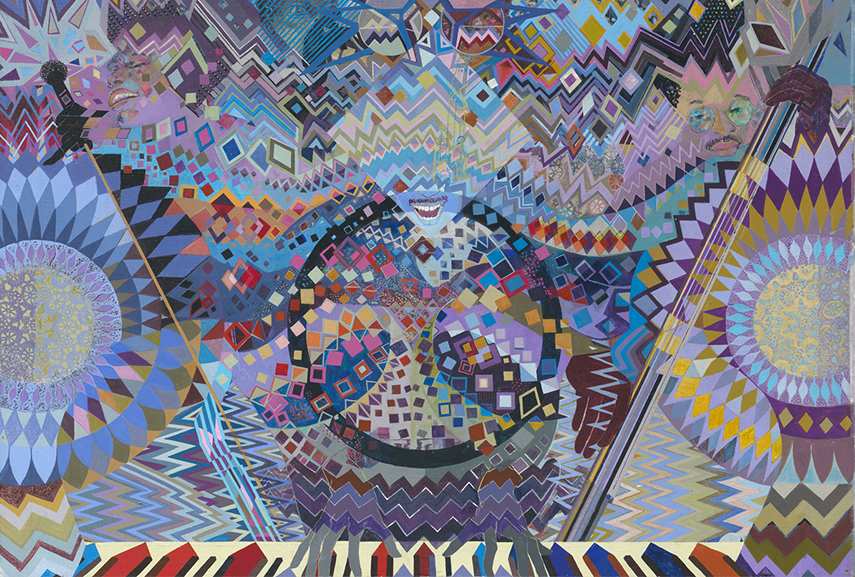

The creators and activists who propagated Black Arts all set out to collaboratively establish something referred to as Black aesthetic, a notion that was inscribed within all artistic forms, recognizable in every art genre. It was present in the highly improvisational spontaneity of Jazz music, the melodic aspects of Black poetry, the interactive, expressive approach pursued by African American dancers and performers, etc.

Imamu Amiri Baraka

Widely perceived as the father of the Black Arts Movement, the eminent African American poet was one of the most pertinent figures of the 20th century poetry and drama. Although he was born Everett Leroy Jones, he invented a moniker LeRoi Jones and became connected to other writers of the Beat generation in the late 50's. Since he was already an established artist and play-writer at the time of the advent of the movement, many people find his turn to Black nationalism as a breaking point in the Black Arts history. His biggest contribution was the founding of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre / School (BARTS), a theatre that operated for a short period of time, but its influence remained strong in the following years. In 1968, he started signing his work under the name Amiri Baraka. By the middle of the 1970's, Baraka became a Marxist, which was one of the main reasons why the Black Arts Movement era ended.

Nikki Giovanni

Nikki Giovanni is of the most famous female poets related to the movement, along with Sonia Sanchez and Rosa Guy. The poet has written 30 books of poetry so far and some of the most famous among them have brought her great recognition, after which she was given the Princess of Black Poetry title by the New York Times and the Woman of the Year by Ebony magazine in 1970. Apart from her engagement in writing and poetry, she became known as one of the most devoted advocates of the Hip Hop subculture, which she sees as "a modern day civil rights movement". She has been part of the Virginia Tech faculty teaching staff since 1987, where she is a University Distinguished Professor today.

Jeff Donaldson

Jeff Donaldson is widely considered the most prolific visual authors related to the movement. It is considered that his work, specifically his contribution to the famous Wall of Respect mural, inspired the Outdoor Mural movement that operated later in many American cities. Donaldson was tightly connected with OBAC and Afri-Cobra (which, until some point, was known only as Cobra), listed as a co-founder of both. Donaldson was a propagator of the trans-African aesthetics, which the artist himself described as characterized by "high energy color, rhythmic linear effects, flat patterning, form-filled composition and picture plane compartmentalization.". He was also an educator, a chairman at Howard university, who revolutionized the program and made it what it is today.

Betye Saar

Greatly moved by the work of Joseph Cornell and raised in Los Angeles, Betye Saar came from a slightly different background than most of the community members mentioned previously. However, as much as she was influenced by Cornell's boxes, equal was her desire to acquire identity through artistic expression and to tell stories about African-Americans. Her seminal work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima from 1972, became known as one of the most important Black Arts works. She was famous for her contribution to assemblage, but she was no stranger to printmaking, as another form of appropriation in art. Saar is a respected artist, acclaimed and praised even outside the confines of the United States.

Faith Ringgold

Although she was trained to become a sculptor and educated according to Western standards, Faith Ringgold eventually developed a style of her own that rarely includes classical approach to sculpture. Through her art, Ringgold refers to her African heritage and reflects on her African American identity. The artist became known for her narrative quilts, which she began creating in 1979, after seeing several 14th and 15th century Nepali paintings - thangkas, framed with fabric borders. Many critics agree that this was the key moment in her career, but also a game changer for the textile art genre. Her quilts often illustrated the stories related to life in Harlem, but also the sufferings of African American slaves, reimagined by the artist. Faith made the quilts with the help from her mother, a famous designer.

Significance and Legacy

Although the movement does not exist as such today - the members took separate ways, as their political views started diverging in 1974 - we might be able to recognize its spirit echoing in today’s Rhythm and Blues, Gospel, even Hip Hop and Rap music, which come as valid incarnations of the “spoken word” tradition.

On the other hand, the matter of race and identity continues to be an engaging topic that concerns creatives of African descent (which is not to say that the topic does not bother people of other races). Nonetheless, the Black Arts Movement was definitely one of the most successful liberating projects of the 20th century, inasmuch as it was non-violent, inspiring and affirmative, and yet it truly did establish the Black aesthetic as we know it today.

One of the most important aspects and goals of the Black Arts Movements was also the one that made it liable to accusations of being counter-racist (if misinterpreted). Most of the members were not that much interested in evaluating themselves as superimposed against the white race or the rest of America, but were rather concerned with structuring and determining the identity of their own race with regard to itself.

In other words, the African American people openly took pride in being black and worked to improve, or rather to define, a clear perception of themselves. This was, naturally, followed by a certain amount of exclusiveness, but it was necessary in order to fulfill the self-determination that the Black Power Concept aimed to achieve in order to build a reality of its own, independent from the Western system, according to which everything and everyone should be assessed either as similar to or different from the Anglo culture: "Liberation is impossible if we fail to see ourselves in more positive terms. For without a change of vision, we are slaves to the oppressor's ideas and values --ideas and values that finally attack the very core of our existence. Therefore, we must see the world in terms of our own realities.[3]"

Editors’ Tip: New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement

This book brings together a collection of seventeen essays that examine and explain the complexity of the Black Arts Movement. It delves into the characteristics that define the movement, relating it to other movements that flourished in the same era and analyzing the political context of the 60's. They touch upon some of the movement's leading propagators, such as Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, Gwendolyn Brooks, Sonia Sanchez, Betye Saar, Jeff Donaldson, and Haki Madhubuti.

References:

-

- Anonymous, African-American Culture, Wikipedia. [September 4th, 2016]

- Jones, L., Baraka, A., 1965, The Revolutionary Theatre, National Humanities Center [September 4th, 2016]

- Neal, L., 1969, Black Art and Black Liberation, University of Virginia [September 4th, 2016]

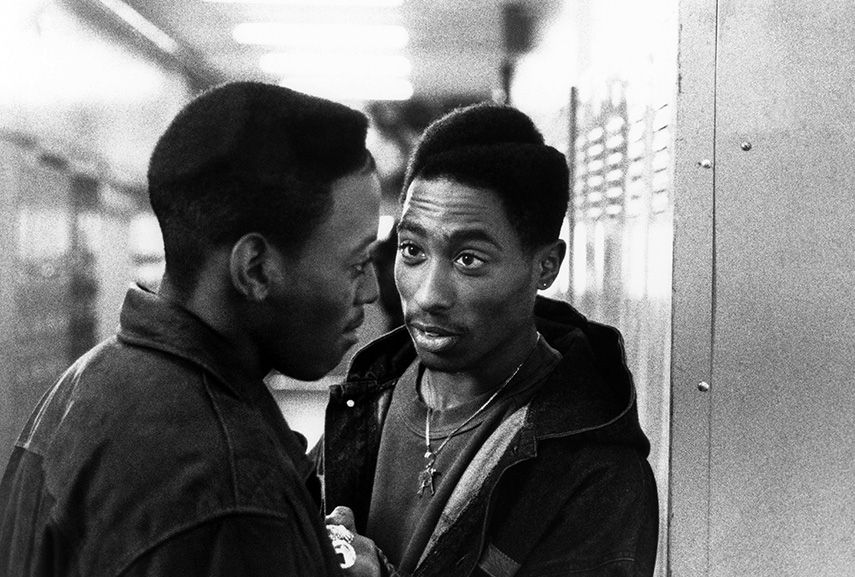

Featured images in slider: Barbara Jones Hogu - Unite; Martin Luther King, promoting non-violence at a protest; Stokely Carmichael, speaking at the University of California's Greek Theater, 1966. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.