Pinus nigra - Euforgen

Pinus nigra - Euforgen

Pinus nigra - Euforgen

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

EUFORGEN<br />

Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use<br />

European black pine<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong><br />

V. Isajev 1 , B. Fady 2 , H. Semerci 3 and V. Andonovski 4<br />

1<br />

Forestry Faculty of Belgrade University, Belgrade, Serbia and<br />

Montenegro<br />

2<br />

INRA, Mediterranean Forest Research Unit, Avignon, France<br />

3<br />

Forest Tree Seeds&Tree Breeding Research Directorate, Ankara,Turkey<br />

4<br />

Faculty of Forestry, Skopje, Macedonia FYR<br />

These Technical Guidelines are intended to assist those who cherish the valuable European<br />

black pine genepool and its inheritance, through conserving valuable seed sources or use in<br />

practical forestry. The focus is on conserving the genetic diversity of the species at the European<br />

scale. The recommendations provided in this module should be regarded as a commonly agreed<br />

basis to be complemented and further developed in local, national or regional conditions. The<br />

Guidelines are based on the available knowledge of the species and on widely accepted<br />

methods for the conservation of forest genetic resources.<br />

Biology and ecology<br />

The European black pine (<strong>Pinus</strong><br />

<strong>nigra</strong> Arnold) grows up to 30<br />

(rarely 40–50) m tall, with a trunk<br />

that is usually straight. The bark<br />

is light grey to dark grey-brown,<br />

deeply furrowed longitudinally on<br />

older trees. The crown is broadly<br />

conical on young trees, umbrella-shaped<br />

on older trees,<br />

especially in shallow soil<br />

on rocky terrain.<br />

Branch tips are<br />

slightly ascending<br />

on young trees; on<br />

older trees only<br />

branches at the top<br />

part of the crown<br />

have upturned tips.<br />

Needles are rather<br />

stiff, 8–16 cm long,<br />

1–2 mm in diameter,<br />

straight or curved, finely<br />

serrated. Resin ducts are<br />

median. Leaf sheath is persistent,<br />

10–12 mm long.<br />

Black pine is a monoecious<br />

wind-pollinated conifer, and its<br />

seeds are wind dispersed.<br />

Flowering occurs every year,<br />

although seed yield is abundant<br />

only every 2–4 years. Trees reach<br />

sexual maturity at 15–20 years in<br />

their natural habitat. Flowers<br />

appear in May. Female inflorescences<br />

are reddish, and male<br />

catkins are yellow. Fecundation<br />

occurs 13 months after pollination.<br />

Cones are sessile and horizontally<br />

spreading, 4–8 cm long,<br />

2–4 cm wide, yellow-brown or<br />

light yellow and glossy. They<br />

ripen from September to October<br />

of the second year, and open<br />

in the third year after pollination.<br />

Cones contain 30–40 seeds, of<br />

which half can germinate. Seeds<br />

are grey, 5–7 mm long, with a<br />

wing 19–26 mm long. Germination<br />

can occur without stratification<br />

although this technique is<br />

often used in forest nurseries<br />

(30–60 day moist +5°C treatment).<br />

Black pine is an obligate<br />

seeder under natural conditions.<br />

Most black pine subspecies<br />

(see Distribution) grow in a<br />

Mediterranean-type climate,<br />

except P.n. <strong>nigra</strong> which is more<br />

typically temperate. Bioclimatic<br />

conditions range from humid<br />

(800–1000 mm annual rainfall) as

inus <strong>Pinus</strong><br />

ropean black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pineP<br />

in P.n. mauretanica or P.n. laricio,<br />

to subhumid (600–800 mm) as in<br />

P.n. pallasiana in Cyprus, to<br />

semi-arid (400–600 mm) as<br />

in P.n. pallasiana in Anatolia.<br />

The optimal altitudinal<br />

range of black pine is<br />

between 800 to 1500 m.<br />

However, a considerable altitudinal<br />

variation can be<br />

observed: from 350 to 1000 m<br />

in Italy (P.n. <strong>nigra</strong>) and on the<br />

Croatian coast (P.n. dalmatica),<br />

from 500 to 900 m in the French<br />

Pyrenees and 1600 to 2000 m in<br />

Spain (P.n. salzmannii), from<br />

1000 to 1600 m in Corsica (P.n.<br />

laricio), from 1000 to 2200 m in<br />

the Taurus mountains and 1400<br />

to 1800 m in Cyprus (P.n. pallasiana)<br />

and from 1600 to 1800 m<br />

in North Africa (P.n. mauretanica).<br />

Black pine can grow on a<br />

variety of substrates: limestone<br />

(e.g. P.n. mauretanica, P.n. dalmatica,<br />

P.n. pallasiana in Central<br />

Greece), dolomites (e.g. P.n.<br />

<strong>nigra</strong> in northern Italy and Austria,<br />

P.n. salzmanni in the<br />

Cévennes, France), acidic soils<br />

(P. n. laricio, P.n. pallasiana in<br />

Anatolia, P. n. salzmanni in the<br />

French Pyrenees) or volcanic<br />

soils (P.n. laricio in Sicily).<br />

Black pine is a light-demanding<br />

species, intolerant of shade<br />

but resistant to wind and<br />

drought. It grows in pure stands<br />

or more rarely in association with<br />

other pines such as P. sylvestris<br />

or P. uncinata.<br />

Distribution<br />

Black pine extends over more<br />

than 3.5 million hectares from<br />

western North Africa through<br />

southern Europe to Asia<br />

Minor. Owing to this large<br />

albeit discontinuous range<br />

and its large genetic and<br />

phenotypic variability, it<br />

is regarded as a collective<br />

species. Although<br />

there is no definite consensus<br />

on its taxonomy,<br />

six main subspecies can<br />

be recognized from North Africa<br />

to the Crimea.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> mauretanica<br />

(Maire et Peyerimh.) Heywood<br />

covers only a few hectares in the<br />

Rif mountains of Morocco and the<br />

Djurdjura mountains of Algeria.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> salzmannii (Dunal)<br />

Franco (syn: P. n. clusiana, P. n.<br />

pyrenaica) covers extensive<br />

areas in Spain (over 350 000 ha<br />

from Andalucia to Catalunia and<br />

on the southern slopes of the<br />

Pyrenees) and is found in a few<br />

isolated populations in the Pyrenees<br />

and Cévennes in France.<br />

It is sometimes referred to as the<br />

Pyrenean pine.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> laricio (Poiret) is<br />

found in Corsica (Corsican pine)<br />

over 22 000 ha, in Calabria<br />

(where it is also recognized as P.<br />

n. l. calabrica, the Calabrian pine)<br />

and in Sicily.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> (syn: P.n.<br />

austriaca Höss, P.n. nigricans<br />

Host, the Austrian pine) is found<br />

from Italy in the Apennines to<br />

northern Greece through the<br />

Julian Alps and the Balkan<br />

mountains, covering more than<br />

800 000 ha.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> dalmatica (Vis.)<br />

Franco, the Dalmatian pine, is<br />

found on a few islands off the<br />

coast of Croatia and on the<br />

southern slopes of the Dinaric<br />

Alps.<br />

<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> pallasiana (Lamb.)<br />

Holmboe covers extensive areas,<br />

mostly in Greece and Turkey (2.5<br />

million ha, 8% of total forest<br />

area) and possibly as far west as<br />

Bulgaria. It can also be found in<br />

Cyprus and the Crimea. It is<br />

sometimes referred to as the<br />

Crimean pine.

inus <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European b<br />

Importance and use<br />

Black pine is one of the most<br />

economically important native<br />

conifers in southern Europe. Early<br />

growth is rather fast. It is widely<br />

planted outside its natural<br />

range. Wood is durable and rich<br />

in resin, easy to process.<br />

P.n. laricio is appreciated<br />

for building and<br />

roofing because of its<br />

straightness and thin branches.<br />

If properly thinned, its low<br />

amount of duramen makes it a<br />

fine carpentry and cabinetry<br />

wood. The same use can be<br />

made of Calabrian pine, although<br />

it is more branchy. Wood of P.n.<br />

<strong>nigra</strong> is of lower quality and thus<br />

restricted to lower-grade building<br />

wood and the making of crates.<br />

Black pine has a mean productivity<br />

of 8–20 m 3 ha -1 yr -1 when<br />

grown as a monoculture on<br />

fertile soils. In natural<br />

conditions, productivity<br />

is 6–10 m 3 ha -1 yr -1 and<br />

down to less then 3 m 3 ha -1<br />

yr -1 on the driest sites.<br />

Because of its ability to<br />

develop well on open lands<br />

and in ecologically demanding<br />

situations, Austrian pine was<br />

intensively used during 19 th and<br />

early 20 th century reforestation<br />

programmes, e.g. in the French<br />

southern Alps for landslide control<br />

and land rehabilitation and in<br />

England and the USA for sanddune<br />

fixation and as a windbreak.<br />

Currently P.n. laricio is the<br />

most important reforestation<br />

species in southern England as<br />

well as in some French regions<br />

(e.g. Loire valley).<br />

Black pine is also valued for<br />

landscaping, both in parks (isolated<br />

trees or in groups) and in<br />

urban and industrial contexts<br />

because of its tolerance to pollution.<br />

It is one of the most<br />

common introduced ornamentals<br />

in the USA. Other uses<br />

include Christmas trees, fuel<br />

wood and poles.<br />

Black pine is included in<br />

the European Council Directive<br />

1999/105/CE (December<br />

22 1999) on the marketing<br />

of forest reproductive<br />

material. Minimum<br />

requirements have to<br />

be met before black<br />

pine seed can be<br />

sold for reforestation.<br />

Genetic knowledge<br />

The first black-pine-type fossils<br />

date to the Miocene, about 20<br />

million years ago. The ice cycles<br />

that shaped the Quaternary period<br />

in Europe are believed to have<br />

been responsible for the currently<br />

very discontinuous range of black<br />

pine. This geographic separation<br />

did not result in mating barriers,<br />

and all subspecies are interfertile<br />

under experimental conditions.<br />

Studies using morphological and<br />

genetic markers have confirmed<br />

the common phylogenetic origin<br />

of all black pines. The most divergent<br />

and genetically original European<br />

groups are P.n. salzmanii<br />

and P. n. laricio, although P.n.<br />

<strong>nigra</strong>, dalmatica and pallasiana<br />

appear quite similar. The amount<br />

of genetic diversity is also high<br />

within populations. Experiments<br />

measuring adaptive traits have<br />

revealed strong within- and<br />

among-population variability for<br />

traits such as vigour, form and<br />

drought, frost and disease resistance.<br />

It is this huge adaptive plasticity<br />

that has made black pine<br />

such a favourite for reforestation<br />

projects over a wide range of<br />

environments.<br />

In the middle of the 20 th century,<br />

several provenance trials<br />

were established independently<br />

in Europe, the USA and New<br />

Zealand. The Corsican and Calabrian<br />

black pine provenances<br />

were found to be the best in<br />

almost every respect on siliceous<br />

soils. They had consistently

ack pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>Eu<br />

excellent stem form and branching<br />

habit, gave the greatest volume<br />

production and were hardy<br />

against winter and late frosts<br />

(except in north-central USA).<br />

The major defect reported is<br />

branch forking, which is both<br />

heritable and highly correlated<br />

with polycyclism and branch<br />

angle. On calcareous soils, P.n.<br />

laricio does not perform well and<br />

is to be replaced by the slowergrowing<br />

but more Ca-tolerant<br />

P.n. <strong>nigra</strong>. In dry climates (as in<br />

inner Anatolia, Turkey), black<br />

pine is slow growing and breeding<br />

programmes for such zones<br />

are focused on improving growth<br />

rate and increasing drought and<br />

frost tolerance through withinpopulation<br />

selection.<br />

Intraspecific hybridization is<br />

easily performed among all black<br />

pine subspecies (a further proof<br />

of phylogenetic relatedness), but<br />

has not contributed any outstanding<br />

genotypes to breeding<br />

programmes so far. Interspecific<br />

crosses seem to be possible at a<br />

low survival rate with P.<br />

sylvestris.<br />

Black pine seed orchards<br />

have been established in several<br />

European countries, e.g. in France<br />

there are one Calabrian pine and<br />

two Corsican pine seed orchards.<br />

Current experiments in vegetative<br />

propagation include micropropagation<br />

of zygotic embryos and<br />

brachyblasts as well as somatic<br />

embryogenesis. Propagation by<br />

grafting has been known since<br />

1820; the method generally used<br />

is lateral grafting.<br />

Threats to<br />

genetic diversity<br />

Black pine is not recognized as a<br />

threatened species although<br />

some of its sub-Mediterranean<br />

endemic populations constitute<br />

priority habitats under the EU<br />

Natura 2000 directive (Habitat<br />

Directive n° 92/43/CEE, May 21<br />

1992).<br />

Extensive plantations were<br />

often made across Europe in the<br />

past two centuries with material<br />

from unknown and/or very distant<br />

sources for which no historical<br />

traces currently exist. This<br />

has probably resulted in extensive<br />

mixing of local and imported<br />

genepools all over the distribution<br />

area of black pine.<br />

Damaging insects include<br />

European black pine shoot moth<br />

(Rhyacionia buoliana), pine processionary<br />

caterpillar (Thaumetopoea<br />

pityocampa), especially<br />

in warm and dry climates, and tip<br />

blight (Sphaeropsis sapinea),<br />

which has been particularly<br />

active in France and Turkey in<br />

1990’s. Other pests such as<br />

Acantholyda hieroglyphica, Diprion<br />

pini, Pissodes validirostis and<br />

Monophlebus hellenicus have<br />

been active in Turkey. Most<br />

recently, an increase in the<br />

impact of a needle blight known<br />

as the ‘red band disease’ (Dothistroma<br />

septospora) has been<br />

reported.

Pinu<br />

European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black<br />

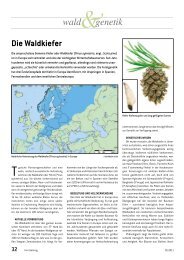

Distribution range of European<br />

black pine<br />

In areas where black pine is<br />

widespread and very important<br />

for forestry, factors such as forest<br />

fires and illegal cutting cause<br />

serious damage. In areas where it<br />

occurs in small isolated populations,<br />

major risks come from any<br />

factor that may provoke local<br />

extinction, either through illegal<br />

cutting and fires or through<br />

hybridization (‘genetic pollution’)<br />

from planted black pines belonging<br />

to other subspecies. Original<br />

and rare varieties such as P. <strong>nigra</strong><br />

var. pyramidalis or P. <strong>nigra</strong> var.<br />

sheneriana in Turkey are under<br />

identical threats.<br />

Guidelines for genetic<br />

conservation and use<br />

Because black pine of different<br />

origins has been extensively<br />

planted, it is now important to<br />

identify authochthonous populations.<br />

This undertaking should be<br />

carried out at the international<br />

level. In each country, an inventory<br />

should be made to define<br />

the geographical distribution of<br />

the species, its conservation status,<br />

threats and potential uses.<br />

Breeding activities provide valuable<br />

information by defining<br />

potential plantation, seed collection<br />

and transfer zones. In situ<br />

conservation activities should be<br />

encouraged separately as seed<br />

stands and gene conservation<br />

forests. Those do not serve the<br />

same goal and should not<br />

always be identical, especially to<br />

make the conservation of marginal<br />

populations possible. An<br />

international in situ network of<br />

100–120 stands would seem<br />

appropriate to represent the natural<br />

ecological and genetic variability<br />

of black pines.<br />

As intraspecific hybridization<br />

is easy among black pines, exotic<br />

or improved black pines should<br />

not be planted in the vicinity of<br />

autochthonous and naturalized<br />

stands. This is particularly true for<br />

localized and fragmented sub-

s <strong>Pinus</strong> pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>European black pine<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>Euro<br />

EUFORGEN<br />

These Technical Guidelines were<br />

produced by members of the<br />

EUFORGEN Conifers Network.<br />

The objective of the Network is to<br />

identify minimum genetic conservation<br />

requirements in the long<br />

term in Europe, in order to reduce<br />

the overall conservation cost and<br />

to improve the quality of standards<br />

in each country.<br />

species such as P.n. laricio, and is of extreme importance for subspecies<br />

that are threatened, such as P.n. salzmanii in France and P.n.<br />

mauretanica in North Africa. For these subspecies and other varieties<br />

of rare occurrence, ex situ conservation is appropriate and urgent. As<br />

a step in that direction, in 1999 a gene conservation forest was selected<br />

in Turkey for the rare P. <strong>nigra</strong> var. pyramidalis.<br />

Information on the provenance and progeny trials established<br />

throughout Europe should be entered in a database. This network of<br />

experimental sites could be used for ex situ conservation of black<br />

pine. Marginal areas might need to be further sampled to strengthen<br />

this network and possibly planted as ex situ seed orchards to re-install<br />

depleted resources.<br />

Citation: Isajev, V., B. Fady, H.<br />

Semerci and V. Andonovski.<br />

2004. EUFORGEN Technical<br />

Guidelines for genetic conservation<br />

and use for European black<br />

pine (<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>). International<br />

Plant Genetic Resources Institute,<br />

Rome, Italy. 6 pages.<br />

Drawings: <strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong>, Claudio<br />

Giordano. © IPGRI, 2003.<br />

ISBN 92-9043-659-X<br />

Selected bibliography<br />

Lauranson-Broyer, J. and Ph. Lebreton. 1995. Flavonic chemosystematics of<br />

the specific complex <strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> Arn. Pp. 181-188 in Population genetics<br />

and genetic conservation of forest trees (P. Baradat, W.T. Adams and G.<br />

Müller-Starck, eds.). SPB Academic Publishing, Amsterdam.<br />

Nikolic, D. and N. Tucik. 1983. Isoenzyme variation within and among populations<br />

of European black pines (<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> Arnold). Silvae Genetica 32(3-<br />

4):80-89.<br />

Quézel, P. and F. Médail. 2003. Ecologie et biogéographie des forêts du bassin<br />

méditerranéen. Elsevier, Paris.<br />

Tutin, T.G., V.H. Heywood, N.A. Burgess, D.M. Moore, D.H. Valentine, S.M.<br />

Walters and D.A. Webb, eds. 1983. Flora Europaea, Vol 1, 2nd edition, pp.<br />

40-44. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.<br />

Vidakovic, M. 1974. Genetics of European black pine (<strong>Pinus</strong> <strong>nigra</strong> Arn.). Ann.<br />

Forest. 6/3 JAZU Zagreb:57-86.<br />

`<br />

EUFORGEN secretariat c/o IPGRI<br />

Via dei Tre Denari, 472/a<br />

00057 Maccarese (Fiumicino)<br />

Rome, Italy<br />

Tel. (+39)066118251<br />

Fax: (+39)0661979661<br />

euf_secretariat@cgiar.org<br />

More information<br />

www.euforgen.org