‘I’ve got the blurbs you ordered, sir.”

“Put them over there, between the bons mots and the charmingly off-topic introductory paragraphs.”

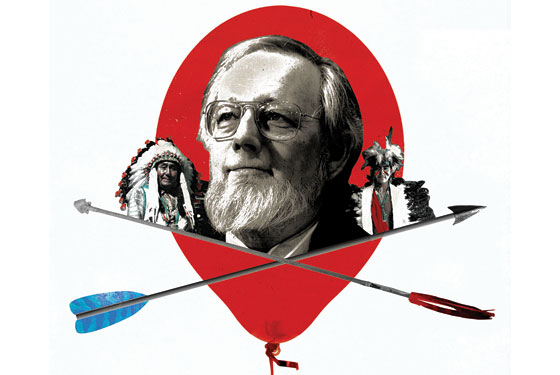

It was stiflingly hot in the book-review factory. From the riveted inner pod of my cantaloupe-shaped command module, I surveyed the factory floor. My laborers were all perched on the shoulders of little native page-turners, reading advance copies of Flying to America, the uncollected short stories of Donald Barthelme. Everyone was sweating furiously. Evenings are not often this hot, even in Cleveland, during the solstice, inside the volcano. “Flip!” I shouted from the module, and the page-turners, who are paid generously for work they enjoy, turned the pages. I listened as my laborers began to debate the book’s significance. Some of them—principally Dom, Nick, and Terry, a few of the mid-level summarizers—were unreservedly excited. They considered Barthelme to be the purest and most readable exponent of American postmodernism (funnier than Pynchon, smarter than Barth, riskier than DeLillo) and his final uncollected stories to be a fist-size jewel plucked from the nation’s cultural tiara by the cat burglar of premature death. Others—namely Sandra, Melanie, Crosseyed Sandy, Honoré de Balzac, the vice-president of the United States, and especially Nancy—had negative feelings. Their sense was that Barthelme had already issued two canonical collections before his death, Sixty Stories and Forty Stories, and that this book was just another vulgar cashing-in on a steady old brand, the highbrow equivalent of selling chocolate-covered synthetic reproductions of Elvis Presley’s fingernail clippings. And anyway, said Nancy, even at his best Barthelme was a charlatan peddling pretentious ironic word-salad. Did anyone even read him anymore? she asked.

“Flip!” I shouted, and the wrists of the native page-turners once again sprang elegantly into action.

Nancy’s comments angered me. I had been reading Barthelme lately, laughing at, among other stories, “The Balloon,” in which a giant balloon is suddenly inflated over Manhattan, from 14th Street to Central Park, and the citizens wonder what it means and develop private rituals with it until it disappears. In order to suppress my anger, I walked across the factory floor (the module was equipped with animatronic legs), and as I walked I rehearsed in my mind the lyrics of a popular gangsta-rap song that recounted the major achievements of Donald Barthelme:

For 25 years, he smuggled the avant-garde into The New Yorker

He subverted bourgeois notions of comfortable form

(Uh, uh)

He shared DNA with the great absurdist-intellectual comic prophets of the sixties (Dylan,

Python—what what, Warhol—uh, Woody Allen—what)

He invented bat flatulence

(Batulence! Batulence!)

“Would it be possible for someone here to speak in a more expository way?” asked Nancy. “Just so we can maybe know what’s going on?”

Professor Background stood up, lit his pipe, clipped on his beard, and began expositioning. He was tenured in American literature at nine universities worldwide and, although he had recently tried to assassinate the vice-president, we kept him on retainer to lend our reviews a certain eggheaded frisson. “The American short story,” he said, “is a field of mythic successions. When Hemingway shot himself in the head in 1961, Donald Barthelme blew, fully formed, out of the exit wound. Like Papa he was a hard-drinking former journalist, voracious reader, serial husband, lover of the declarative sentence, and innovator in both style and subject. But while Hemingway’s fiction spoke in the terse telegraphic brutal old-fashioned distant ethos of the World Wars, Barthelme’s coalesced in the era of Vietnam, the first televised war. He discarded all the passé little signposts of intelligibility—the Enlightenment handcuffs of neatness, order, form—in favor of surreal disjunctions, commercial breaks, superheroes, cowboys and Indians and Kierkegaard. As Hugh Kenner once wrote about Barthelme’s great hero, Samuel Beckett, we read these stories not for plot or character but for ‘the unquenchable lust to know what will happen in the next ten words.’ The fundamental aesthetic difference is expressed most clearly, I believe, in the authors’ beards. Hemingway’s was white, sage, and conventional. Barthelme’s was pointy and cheek-eschewing, with a dark stripe running from his lower lip down to its wispy goat-point. It problematized the very notion of authorial beards. It looked like a hairy cat eye blinking on the bottom half of his face. It was a category error of facial excrescence. Do a Google Image search. I will now take three questions.”

“How do you pronounce his name?” asked one of the native page-turners.

“Hiz Naym,” said Professor Background.

“No … Bar-telm? Bar-thelm?”

“BARTH-el-may.”

I examined the blurbs. The delivery girl had left them, against my express wishes, leaning against some old subtitles in the corner. They were entirely lacking in context. “Vanguard of the avant-garde.” “Not only X and Y, but also Z!” “Your mother enthusiastically distributes gonorrhea.” It would be a difficult choice. The blurb had to sum up our official attitude to the book, to be prominent and yet slipped in as subtly as the body of an alligator into a slightly larger alligator. It had to be simple and obvious while retaining a certain soul-affirming tangy connaissance.

The workers kept assembling the review. Little by little they chiseled and joined its necessary parts: the introduction, the name-dropping (Borges, Calvino, Gaddis), the ironic twist (“Barthelme’s career, which was built out of stories that refused to end tidily, has now found a tidy end”). They taxonomized Flying to America’s Barthelmanian treasures: three previously unpublished stories, one of which he was working on at his death; his first published story (1959); the winning entry of a contest in which the author asked readers to finish a story of which he’d written the first three paragraphs; and a bunch of masterful work from The New Yorker. Some of the early material was purely educational, an opportunity to watch a young genius feeling for the proper ratio of his signature components—oddity, normalcy, aphorisms, non sequiturs, cliché, jargon, lyricism. (“Every writer in the country can write a beautiful sentence, or a hundred,” he wrote. “What I am interested in is the ugly sentence that is also somehow beautiful.”) But some of these stories—“Flying to America,” “Three,” “Tickets”—were among his very best.

Midway through the review, my laborers began to giggle savagely, causing the native page-turners to buck and sway beneath them.

“My emoticonsciousness is LOLing,” said Honoré de Balzac.

“Totes,” said the vice-president of the United States.

The phone in the command module kept ringing. My mother called to recount in great detail the plot of a film called The Toxic Avenger. My wife called to say that birds, whole flocks of them, had finally discovered the feeder in our kitchen window. My sister shouted into the receiver that she had recently adopted multiple cats. In the distance I heard the trumpets of warring parties from rival book-review sections, advancing upon us to steal the golden nectar of our methods and opinions. I knew that by the time they arrived our blurb would be fully mature, and that it would smite them handily. I do not know to which country the native boys are native. My book-review factory was not in Cleveland.

Flying to America

By Donald Barthelme. Shoemaker & Hoard. 432 pages. $26.